The local crop varieties (farmers’ varieties) registration system in Nepal: Past, present and future

Bal Krishna Joshia,*, Pradip Thapaa, Benu Prasaib and Dila Ram Bhandarib

a National Agriculture Genetic Resources Center (Genebank), NARC, Khumaltar, Nepal

b Seed Quality Control Center (SQCC), MoALD, Kathmandu, Nepal

* Corresponding author: Bal Krishna Joshi (joshibalak@yahoo.com)

Abstract: Farmers’ varieties, characterized by their broad genetic base and ecological resilience, were historically not recognized by Nepal’s formal seed system. However, after decades of research, policy dialogue and advocacy efforts, the Seed Regulation of 2013 introduced a provision allowing farming communities to register their varieties through a simplified process. This milestone was further reinforced by the Seed Act of 2022 and the Seed Regulation of 2024, which legally defined native and local landraces, ensuring their formal recognition and protection. Despite these advancements, market opportunities for site-specific landraces remain limited, posing a challenge for widespread commercialization. Nevertheless, the registration system has significantly contributed to Nepal’s seed sovereignty, empowering farmers economically, promoting agrobiodiversity conservation and enhancing agricultural sustainability. By integrating formal recognition, economic incentives and ecological resilience, Nepal is fostering a farmer-driven, sustainable agricultural future where local varieties play a crucial role in food, nutrition, health and business security, climate adaptation and rural livelihoods.

Keywords: Formal seed system, landrace, seed cycle, farmers’ rights, farmer-managed seed system

Introduction

Nepal is home to approximately 30,000 site-specific crop landraces cultivated across diverse agro-ecological zones, ranging from 60 to 4,700 meters in altitude (Joshi et al, 2020b). Despite this rich genetic diversity, the country remains heavily dependent on foreign germplasms, with 95–100% of its breeding materials sourced from outside (Chaudhary et al, 2016). Only 5% of Nepal’s native agricultural genetic resources (AGRs) have been utilized in research, and just 37 local landraces of 19 crops have contributed to the development of 41 modern varieties (SQCC, 2024; Joshi 2017). This underutilization of indigenous genetic resources highlights a significant gap in Nepal’s agricultural policy and breeding programmes.

Among the six components of AGRs – crops, livestock, forage, agro-insects, agro-microbes, and aquatic – the formal seed system in Nepal only accounts for crops and forages, while farmers continue to maintain and produce all six components (Joshi et al, 2020b). The country’s seed system can be categorized into three broad types based on breeding and legal status: the formal seed system, the non-formal seed system (privately managed system of improved/ exotic varieties without registration), and the informal seed system (traditional farmer-managed system of landraces without formal regulation) (Gurung et al, 2020; Joshi et al, 2020d; LI-BIRD and the Development Fund, 2017). However, with the expansion of the formal seed system, farmers have been largely excluded from the seed registration process, limiting their rights over the seed production cycle (De Jonge et al, 2025). Despite this, the majority of seed transactions in Nepal still occur through informal channels (Gurung et al, 2020; Joshi et al, 2020d).

In Nepal’s formal system, crop varieties can be listed/notified through two mechanisms: registration (in which one-season evaluation data is enough) and release (in which three-season evaluation data is required) (MoAD, 2013; Joshi et al, 2017b). As of September 2025, 956 varieties of 85 different crops had been developed and notified in the national seed board (SQCC, 2024). Various types of cultivars exist within the country, including registered and released (R&R) varieties, native landraces, local varieties, hybrids, open-pollinated varieties (OPVs), exotic varieties, cultivar mixtures, evolutionary populations, composites, and pure lines. Farmers’ varieties are broadly classified into two types: native or indigenous landraces and local varieties or local landraces (MoALD, 2024); both are called farmers’ varieties. A native or indigenous landrace refers to a genotype that has evolved or originated in a specific area, with at least one unique trait or gene that developed in that region and has been traditionally cultivated there. A landrace is a traditional crop population naturally adapted to a local area, not bred by formal breeders, while a variety is a scientifically bred and improved crop developed by a professional plant breeder. A local variety and landrace is a crop that has been fully adapted to a particular area, experiencing zero environmental shock, or any variety that existed in Nepal before 1951 and has been continuously cultivated in a specific region for over 60 years.

Although genetic diversity is key to agricultural sustainability and climate resilience, the formal registration system prioritizes uniformity through distinctness, uniformity and stability (DUS) testing – a criterion designed for commercial breeding rather than for recognizing the diverse nature of farmer-managed landraces (MoALD, 2024). Nepal’s seed regulatory framework requires DUS testing for formal variety registration, which benefits seed companies and breeders but not traditional farmers (MoA, 1997). This restriction further discourages on-farm conservation and the formal recognition of native landraces, undermining their role in sustainable agriculture. Given the increasing challenges posed by climate change and shifting agricultural landscapes, Nepal must balance a localized seed system with a globalized product system to ensure both food security and economic sustainability. Farmers are not just cultivators but also breeders, innovators, and custodians of genetic diversity and traditional knowledge (Gauchan et al, 2020b). They play a critical role as primary sources of agricultural practices, germplasm conservation and sustainable farming techniques.

While formal plant breeders require DUS criteria to identify a variety, farmers recognize and maintain their landraces even with inherent diversity. These landraces, though genetically diverse, retain their identity and functional traits over generations, even in cross-pollinated and open-field conditions. Farmers have developed sophisticated selection and management practices, ensuring that their traditional varieties remain stable and locally adapted. The ability of farmers to maintain the genetic integrity of landraces across different agroecological sites is evidence of the effectiveness of farmer-led conservation strategies.

One of the most effective conservation-through-use approaches is the formal registration of native landraces, which provides legal recognition, enabling farmers to produce, market and benefit from their seeds while ensuring their continued conservation. This approach bridges the gap between informal and formal seed systems, promoting seed sovereignty, economic incentives for farmers, and long-term sustainability of genetic resources. By acknowledging and registering farmers' varieties, Nepal can strengthen on-farm conservation efforts, enhance climate resilience and safeguard agricultural biodiversity for future generations.

To support farmer-led conservation and innovation, Nepal’s agricultural policies must transition from merely formalizing agricultural inputs – such as seeds, pesticides and fertilizers – to formalizing farmer-produced outputs and ensuring market guarantee of each product. Farmers should have full rights over their seeds, traditional knowledge and genetic resources, with an equitable access and benefit-sharing mechanism in place. Recognizing the urgency of agrobiodiversity conservation, this paper examines the evolution of Nepal’s local variety registration system, explores its present challenges, and envisions a future framework that prioritizes farmer empowerment, sustainability and the legal recognition of diverse genetic resources.

Methodology

This study employed a comprehensive approach integrating review, observation, survey and experience (ROSE) to analyze the farmers’ variety registration system in Nepal from 2000 to 2024. The methodology is structured as follows:

- Review of literature and documents: A thorough review of relevant literature, policy documents, reports and Community Biodiversity Registers (CBRs) was conducted to understand the historical and policy evolution of local variety registration. Key sources included national and international publications, government policies, legal frameworks and institutional reports related to farmers’ varieties and agrobiodiversity conservation

- Field observations: Multiple observations were carried out over the years in various settings, including farmers’ fields, agricultural fairs, seed storage facilities, community seed banks and the Nepal (National) Genebank. These observations provided firsthand insights into traditional seed-saving practices, varietal diversity, farmers’ perceptions, and the challenges in the registration process

- Surveys and stakeholder consultations: To gather field-level data and stakeholder perspectives, the study employed 35 focus group discussions (FGDs) with farmers, seed custodians and community-based organizations; 100 key informant interviews (KIIs) involving policymakers, researchers, extension workers and representatives from seed regulatory bodies; 50+ telephone surveys to supplement and verify information from stakeholders across different regions.

- Documentation of authors’ experiences: The experiences of all authors over the study period (2000–2024) were systematically documented, incorporating insights from field engagements, institutional involvement and direct participation in seed registration processes. Challenges faced, major policy shifts, significant events and scientific evidence were synthesized to provide a well-rounded perspective.

This multi-method approach ensured a holistic and evidence-based analysis of the local variety registration system in Nepal, capturing both historical trends and future trajectories. To generate empirical evidence, numerous on-farm trials were conducted to evaluate the performance, adaptability and resilience of different local varieties in varying agroecological conditions. Additionally, the pedigree analysis of many released varieties was carried out to trace their genetic lineage and understand the contributions of farmers' varieties in modern breeding programmes. Both farmers’ varieties and improved varieties were assessed for their genetic diversity, adaptability and farmer preference, providing crucial insights into conservation needs and utilization strategies. A policy gap analysis (mainly through policy document review, implementation status and strategy study, and interaction with farmers, experts and seed companies) was conducted to evaluate the effectiveness of existing legal frameworks and institutional mechanisms for local variety registration. Survey reports were developed based on focus group discussions, key informant interviews and telephone surveys to capture stakeholders' perspectives. The drivers of genetic erosion of native landraces were studied in depth, with efforts made to estimate the percentage of loss and underlying factors contributing to the decline in agrobiodiversity.

Several CBRs maintained by the community were analyzed to document the status and dynamics of local varieties at the community level. A farmers' varietal catalogue (Gurung et al, 2019) of ten communities was developed to systematically document traditional seed diversity, their agronomic traits and their historical significance. To facilitate participatory research and conservation, Five-Cell Analysis, a method (Joshi et al, 2022) used to assess varietal richness and distribution, was conducted in more than ten sites during 2000 to 2012.

The study also incorporated sensory evaluations to assess farmers' and consumers' preferences for specific landraces based on taste, texture, and other quality attributes. Community Seed Banks (CSBs) were established and documented, highlighting their role in the conservation and distribution of local varieties. In addition, nutritional analysis was performed to determine the health benefits of various landraces, and product diversification efforts were undertaken to explore new ways of utilizing traditional crops for economic and food security benefits.

Results and discussion

Historical lessons and conventional practices

Nepal’s past agricultural policies and practices have largely emphasized the promotion of monogenotypes, favoring single, homogeneous and uniform exotic varieties over diverse native landraces (Gauchan et al, 2017; Joshi 2017). This approach led to large-scale cultivation of a few improved varieties, particularly in staple crops like rice, wheat and maize (SQCC, 2024). While these crops have been prioritized in research, education and development, 85% of Nepal’s native agrobiodiversity consists of neglected and underutilized species (NUS) and future/smart crops (F/SC), (Joshi et al, 2020b) which have received little attention in research, development and policy frameworks. As a result, many traditional crops, which are highly nutritious, healthy and climate-resilient, remain underutilized (Joshi, 2017).

The heavy dependence on exotic germplasm and technologies has contributed to the erosion of native crop biodiversity (Chaudhary et al, 2016). Studies indicate that 50–100% of crop biodiversity has been lost in different regions of Nepal, depending on crop type and location (Joshi et al, 2020b).

The existing agricultural policies have also reinforced inequality in access to incentives and services. Only R&R varieties are eligible for government incentives, subsidies and extension support, leaving farmers’ varieties at a disadvantage (Gauchan et al, 2017).

Additionally, past policies have promoted a high seed replacement rate, which prioritizes frequent replacement of traditional varieties with modern hybrids and varieties. While this may enhance yield in the short term, it disrupts traditional seed cycles, making farmers completely dependent on external seed sources and accelerating the loss of indigenous landraces (Gurung et al, 2020; Joshi et al, 2020c). This dependency has gradually eroded farmers' rights (e.g. germplasm as private property, registration provision by an individual farmer, seed saving, marketing, etc.), turning them into mere consumers of commercial seed companies, despite the fact that farmers produce many essential agricultural inputs beyond edible crops.

Farmers’ varieties, also known as native landraces, are an invaluable component of Nepal’s agricultural heritage. These varieties possess rich genetic diversity, which plays a crucial role in maintaining climate-resilient and sustainable agricultural systems (Joshi et al, 2018; 2023a). The greater the genetic diversity, the stronger the adaptive capacity of crops to environmental changes, pests and diseases, ensuring the long-term sustainability of farming (Zhu et al, 2000; Neupane et al, 2023). However, despite their importance, the genetic diversity of landraces has not been fully recognized in national policies, limiting their integration into formal seed systems (Joshi, 2017; MoA, 1997). This lack of policy recognition contradicts the fundamental need for genetic diversity in resilient agriculture.

Scientific and empirical evidences for policy reformulation

Between 2000 and 2024, extensive research, field trials, policy analyses and participatory approaches have generated both empirical and scientific evidence supporting the advantages of farmers’ varieties over improved varieties (Joshi et al, 2023a). Numerous on-farm trials demonstrated that farmers’ varieties perform better in terms of ecological yield, taste, adaptability, genetic diversity, farmer preferences, risk-bearing capacity and resilience across different agroecological conditions (Shrestha et al, 2013; Sthapit, 2013). Unlike modern hybrids, which often require high external inputs, farmers’ varieties have shown higher adaptability to local environments, making them more sustainable for smallholder farmers (Bajracharya et al, 2012; Poudel et al, 2015; Bhandari et al, 2017; Gauchan et al, 2018; 2020a; Shrestha and Rana, 2018; Gurung et al, 2020; Joshi et al, 2020a; Karkee et al, 2023).

Pedigree analysis of released varieties in Nepal revealed that most of the parent materials used for breeding improved varieties originated from outside the country, emphasizing the reliance on exotic germplasm (Chaudhary et al, 2016; Joshi, 2017). Comparative studies between farmers’ varieties and uniform, exotic varieties highlighted key advantages of local landraces, including higher genetic variation, better taste, climate resilience, low input requirements, nutritional richness and multiple ecological benefits (Joshi et al, 2018; 2023a; Sthapit et al, 2019). Moreover, farmers’ varieties exhibited a high evolutionary rate, making them more adaptive and sustainable in the face of climate change. These findings underscored major policy gaps, as policies before 2013 primarily favoured improved and uniform varieties, often excluding farmers’ varieties from formal recognition and incentives (MoA, 1997).

One major reason for the decline of farmers’ varieties was the aggressive promotion of R&R varieties, which were often incentivized by government policies (Upreti and Upreti, 2002; Joshi et al, 2020b). Farmers have reported a 50–100% loss of traditional landraces, largely attributed to the widespread adoption of modern crop varieties (Joshi et al, 2020d). Farmers reported total failures in some improved varieties due to their lack of adaptability, while complete crop failure was rarely observed in farmers’ varieties. The high genetic diversity within farmers’ varieties allowed them to remain more dynamic, evolving and resilient to climate change and pest outbreaks (Joshi et al, 2023a).

Farmers’ varieties also play a crucial role in ensuring food security, nutrition security, health security, business security and environmental sustainability. For example, landraces of rice, maize and wheat demonstrated yields 20% higher than the national average, while minor crops outperformed improved varieties by 60% (NAGRC, 2024). Additionally, 100% of indigenous varieties still contribute to 83% of total cultivated crops, showing their continued significance in Nepalese agriculture (Gauchan et al, 2020b; Gurung et al, 2020). While modern varieties had higher carbohydrate content, landraces were richer in essential micronutrients, phytochemicals and antioxidants, promoting better nutrition security (Joshi et al, 2020d). Furthermore, since indigenous varieties are grown agroecologically, they contribute to health security by reducing exposure to chemical residues. Their higher market value (Gauchan et al, 2020a), better taste, and balanced nutrient composition provide business security to farmers. Finally, as climate-resilient, organically grown crops with high ecological yields, farmers’ varieties contribute to environmental sustainability and low-risk farming systems in Nepal.

Milestones in farmers’ variety registration

The formal discussion on the comparative advantages of farmers’ varieties over improved R&R varieties began in 2000, marking the initial step towards their recognition in Nepal’s seed system (Table 1). Around this time, Nepal Genebank, Local Initiatives for Biodiversity, Research, and Development (LI-BIRD), and Bioversity International started working collaboratively on policy dialogues, policy gap analysis, and evidence generation to advocate for the importance of farmers’ varieties. Through continuous efforts, the unique advantages and diversity of farmer-managed varieties were explored (through on-farm trials, focus group discussions and interactions with farmers), leading to increased awareness among policymakers, researchers and farming communities.

To provide scientific validation and support for farmers’ varieties registration, participatory on-farm trials were initiated across different districts (Sthapit and Jarvis, 2003). Community-based initiatives played a significant role in generating both scientific and local knowledge. Diversity fairs were organized to showcase and promote farmer-managed seed diversity, while Diversity Field Schools facilitated participatory learning and seed selection processes among farming communities. Participatory landrace enhancement programmes were carried out to improve the productivity and resilience of selected landraces through farmer-led breeding efforts. Diversity blocks were established in different regions to conserve and monitor traditional varieties in situ, ensuring their continued use and adaptation.

To facilitate the recognition and registration of local varieties, various strategies and policy documents were developed to convince the relevant authorities. Several policy dialogues, travelling seminars and field visits were organized to bring together policymakers, researchers, farmers and seed experts at local, provincial and national levels. Regular interaction programmes were conducted with farmers and breeders to understand their concerns and integrate their perspectives into policy discussions. Additionally, workshops, sharingshops and writeshops were held to draft policy recommendations, ensuring a participatory approach to decision-making. Continuous engagement with authorities through publication sharing and organoleptic tests further supported evidence-based policy advocacy.

The initial format, which was simple and accessible online for farmers’ variety registration, was developed by key breeders from Nepal Genebank and the Seed Quality Control Centre (SQCC), ensuring it was farmer-friendly and easy for farming communities to fill out independently (MoAD, 2013). Recognizing the importance of traditional knowledge in the registration process, the format was later revised to include detailed information on origin, cropping history, agromorphological traits, social significance and economic values of farmers’ varieties (MoALD, 2024). This formal format was prepared through a collaborative effort involving plant breeders, seed experts, conservationists and farmers, ensuring that the format was practical, inclusive and scientifically sound. To strengthen institutional and community-level capacities, orientation programmes, training sessions and varietal proposal writeshops were conducted for farmers, researchers and policymakers. Hands-on training in on-farm trials, data recording, and participatory variety selection enabled farmers and researchers to generate robust scientific data to support variety registration.

A significant milestone was the development of detailed guidelines for the registration, production, maintenance and distribution of farmers’ varieties in 2022 by Nepal Genebank, LI-BIRD and CSBs. Special attention was given to maintaining genetic diversity during seed multiplication, reinforcing the importance of conserving the rich agrobiodiversity of farmers’ varieties while promoting their sustainable use and commercialization. This not only enhanced farmers' technical capacities but also provided ownership rights to farmer groups, empowering them to maintain, produce and sell their own seeds legally. Unlike in the past, where the formal seed system detached farmers from the seed cycle, this initiative allowed farmers to regain control over seed management (Gauchan et al, 2017).

To ensure the conservation of original genetic materials, passport data and the original seed lots of registered varieties are maintained by the Nepal Genebank under the Nepal Agricultural Research Council (NARC) (NAGRC, 2024). However, despite these achievements, the registration process in Nepal has so far been limited to orthodox seeds (seeds that can be dried and stored for long periods) (SQCC, 2024). The system still lacks a mechanism for registering non-orthodox seeds, including vegetatively propagated crops, recalcitrant seeds and cultivar mixtures, highlighting the need for further advancements in the farmers’ variety registration framework.

Table 1. Major events in the process of registration of farmers’ varieties in Nepal. Source: Sthapit et al, 1998; Joshi and Witcombe, 2003; Subedi et al, 2005; MoAD, 2013; Chaudhary et al, 2016; Bhandari et al, 2017; Gauchan et al, 2017; Joshi, 2017; Joshi et al, 2017a; Thapa et al, 2019; Joshi et al, 2020b; MoALD, 2022; MoALD, 2024; SQCC, 2024.

|

Year |

Major actions |

Organizations involved |

Remarks |

|---|---|---|---|

|

2000–2012 |

Many round discussions about legal provision for native landraces (e.g. meeting, workshop, travelling seminar, interaction meeting), evidence generation, history and gap analysis, on-farm trial for native landraces |

Nepal Genebank, LI-BIRD, Bioversity International |

Carried out these actions in many districts |

|

2012 |

Accessioning system of Genebank for submitted varieties in Variety Approval, Release and Registration Sub-Committee (VARRSC) coordinated by the Seed Quality Control Centre (SQCC) |

Nepal Genebank |

Nepal Genebank started providing accession numbers and seeds of such varieties are maintained in Nepal Genebank. Only for orthodox seeds |

|

2013 |

Legal provision of registration of native and local landraces of crops (heterogenous varieties): Seed Regulation 2013, Rule-12, By-rule- 2: Annex-1 Schedule (Clause)-D |

SQCC, Nepal Genebank |

Very simple format, at first prepared and made available online |

|

2018 |

Format revision, verification and testing during 2nd National Workshop of Community Seed Banks |

SQCC, Nepal Genebank and LI-BIRD, Community Seed Banks |

Simple existing format elaborated and shared among farmers and breeders |

|

2019 |

Consultation workshop on farmers’ variety registration and commercialization; training workshop on local variety registration process |

Nepal Genebank, LI-BIRD, Community Seed Banks |

Mutual understanding among farmers, seed experts and breeders |

|

2021 |

A training workshop on farmers’ variety registration proposal development |

Nepal Genebank, LI-BIRD, Community Seed Banks |

Practical exercise on format of registration |

|

2022 |

Training, workshop and writeshop for drafting detail guideline on farmers’ variety registration and maintenance, A national workshop on native varieties registration in Nepal: Issues, Achievements and Challenges |

Nepal Genebank, LI-BIRD, Community Seed Banks, SQCC |

Issues of registration and maintenance identified and discussed |

|

2022 |

Seed Act 1988 (2nd amendment) |

SQCC |

Farmers’ variety recognized |

|

2023 |

Details guidelines preparation |

Nepal Genebank, LI-BIRD |

Seed production, maintenance, labelling and marketing |

|

2024 |

Seed regulation (revised) |

SQCC |

Details guidelines and defines native and local landraces |

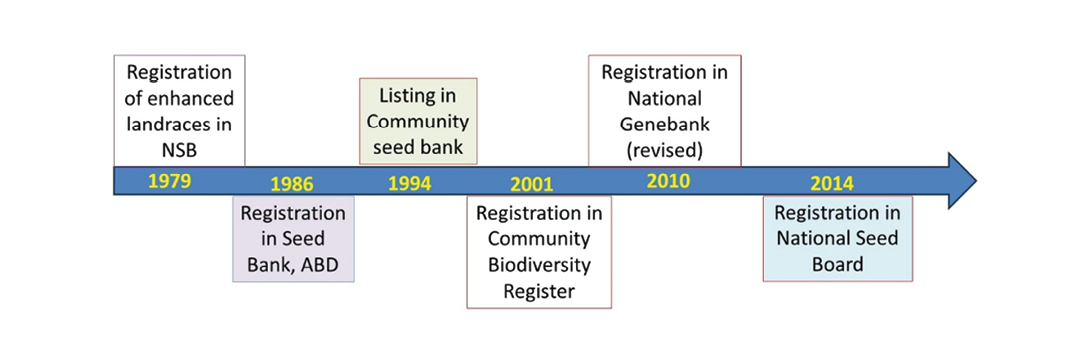

The formal registration of native landraces in Nepal began in 1979, when plant breeders started registering traditional varieties after selection (Figure 1) (Sthapit et al, 1998; SQCC, 2024). However, informal registration of farmers’ varieties had started in 1986 under the Plant Genetic Resource Unit (Seed Bank) of the Agriculture Botany Division. Despite these early efforts, until 2013, only formal plant breeders and research institutes had the authority to register varieties, limiting farmers' ability to legally recognize and commercialize their own traditional seeds (MoA, 1997). A major shift occurred in 2013, when Nepal’s Seed Regulation was amended, allowing groups of farmers to register their landraces in the National Seed Board (NSB) as their own business items (MoAD, 2013). This revision included Schedule D, a simplified format for the registration and release of farmers’ varieties, officially recognizing farmers as breeders. This paved the way for the first-ever formal registration of a farmers’ variety in 2014. The first registered farmers’ variety was broad leaf mustard (Gujmuje Rayo) from Dalchoki, Lalitpur, facilitated by the Dalchoki Community Seed Bank, Nepal Genebank, and SAHAS-Nepal (SQCC, 2024).

The registration process for Gujmuje Rayo and another landrace, Dunde Rayo, involved on-farm trials conducted in Dalchoki, Lalitpur, where all released varieties of broad leaf mustard were tested alongside the farmers’ varieties. The trial was evaluated by experts, farmers, members of the Variety Approval Release and Registration Sub-Committee (VARRSC), the Nepal Genebank team, and SAHAS-Nepal representatives. A travelling seminar and organoleptic test were conducted, where all tested varieties were cooked and evaluated for taste, texture and other consumer preferences. Additionally, simple agromorphological data were collected to support the registration proposal. With technical and institutional support from Nepal Genebank and SAHAS-Nepal, the Dalchoki Community Seed Bank formally submitted a proposal to the NSB for the registration of these varieties. After evaluation, the VARRSC approved the registration under Schedule-D of the Seed Regulation 2013, officially recognizing Gujmuje Rayo as the first registered farmers’ variety in Nepal. This milestone set an important precedent for farmer-led conservation, recognition and commercialization of native landraces, strengthening the integration of traditional seed systems into formal seed governance.

Figure 1. Informal and formal registration practices of native landraces in Nepal. NSB, National Seed Board; ABD, Agriculture Botany Division. Source: Sthapit et al, 1998; Joshi and Witcombe, 2003; Subedi et al, 2005; Subedi et al, 2013; Joshi, 2017; Joshi et al, 2017a; Thapa et al, 2019; SQCC, 2024.

Creating an enabling environment

In this process, multiple stakeholders – including Community Seed Banks and farmers – have been actively engaged. Creating an enabling environment is vital to support the revision of policies. Key mechanisms include regular interaction, field visits, meetings, workshops, on-farm trials, travelling seminars, and training. Among these, two components stand out as especially important: capacity enhancement and policy engagement and advocacy.

Regular capacity-building programmes (training workshops, exchange visits, practical exercises, travelling seminars, writeshops and interactive meetings at local, regional and national levels) were conducted for farmers and relevant stakeholders to strengthen their understanding and skills in various aspects of farmers’ variety registration and conservation in more than 25 districts. Three organizations, namely Nepal Genebank, LI-BIRD and Bioversity International, were directly involved in capacity building. These programmes focused on the values and importance of farmers’ varieties, emphasizing their role in genetic diversity, climate resilience and sustainable agriculture (Gauchan et al, 2016; Gauchan et al, 2020a; Joshi et al, 2020a; 2020b; 2020c). Training sessions covered participatory plant breeding, data generation and documentation, ensuring that farmers could scientifically record and validate their varieties. Additionally, farmers and local stakeholders were trained in PowerPoint preparation and presentation skills, enabling them to effectively communicate their experiences and research findings. These activities fostered collaboration among farmers, researchers, policymakers and conservationists, ultimately strengthening the farmer-led seed system and promoting farmers’ rights and agrobiodiversity conservation in Nepal.

The evidence generated on the benefits of farmers’ varieties was shared, presented and discussed with various stakeholders and key authorities (e.g. MoALD, SQCC, NARC, DoA, LI-BIRD, Institute of Agriculture and Animal Science (IAAS), Center for Crop Development and Agrobiodiversity Conservation (CCDABC), CSB, etc) across Nepal. The key actors were Nepal Genebank, LI-BIRD and Bioversity International. Through policy dialogues, research presentations and interactive discussions, decision-makers were made aware of the ecological, economic and social advantages of integrating local seed systems into formal frameworks. By highlighting the superior adaptability, resilience and sustainability of farmers’ varieties. These engagements successfully influenced authorities to rethink existing policies that primarily favoured uniform and exotic varieties.

To further strengthen the case for farmers’ variety registration, multiple strategies were adopted to enhance the value and understanding of local seed systems. By demonstrating that farmers’ varieties contribute to food security, nutrition, climate resilience and economic benefits, policymakers were encouraged to re-evaluate seed regulations and make them more inclusive of traditional landraces. These efforts have played a significant role in shaping Nepal’s evolving seed policies, ensuring that farmers’ varieties gain formal recognition, legal protection and access to incentives

Seed policy reforms and legal provisions

Further progress was made with the 2022 amendment to the Seed Act, which provided legal recognition of farmers’ varieties and delegated authority to provincial governments to notify and regulate local landraces. The amendment also introduced a provision for collective ownership, allowing CSBs and farmer groups to hold joint ownership of their traditional landraces. Additionally, a committee was proposed in this Act involving key agricultural officers and progressive farmers for the management and governance of local seeds, ensuring that decision-making power remained with local farming communities.

The Seed Regulation 2024 has significantly strengthened the recognition and registration of farmers’ varieties by introducing detailed registration formats (Annex 5 and 6), a Truthful Labelling System, and a clear legal definition of native and local landraces (MoALD, 2024). These revisions marked a crucial step toward securing farmers’ rights, ensuring their ownership, selection, conservation and distribution of landraces while promoting the sustainable use of Nepal’s rich agrobiodiversity. A separate annex has been designated for native and local varieties, providing structured guidelines for their identification and registration. Native varieties are those that have been grown for generations, whereas local varieties are defined as those that have been cultivated in a particular locality for over 50 years (Joshi et al, 2020a; MoALD, 2022). As per Annex 5, farmers or communities can register their native varieties. However, the registration of local varieties follows a different approach under Annex 6, where farmers themselves cannot apply; instead, the process is managed through relevant institutions or governing bodies.

To maintain quality and traceability, farmers’ varieties are classified into distinct seed classes (MoALD, 2024). For seed-propagated crops, the categories include Source Seed and Improved Seed, while for vegetatively propagated crops, the designated classes are Mother Plant and Improved Plant. Furthermore, the Truthful Labelling System ensures transparency and credibility in the marketing of farmers’ varieties. It guarantees that registered varieties meet quality standards while preserving their genetic diversity and adaptability, which are essential for sustainable agriculture and climate resilience. Truthful Labelling System in the seed system refers to a regulatory approach that allows seed producers or sellers to market seeds without undergoing official certification, provided they label the seed packages accurately and honestly with all essential quality information.

Present status and ongoing initiatives

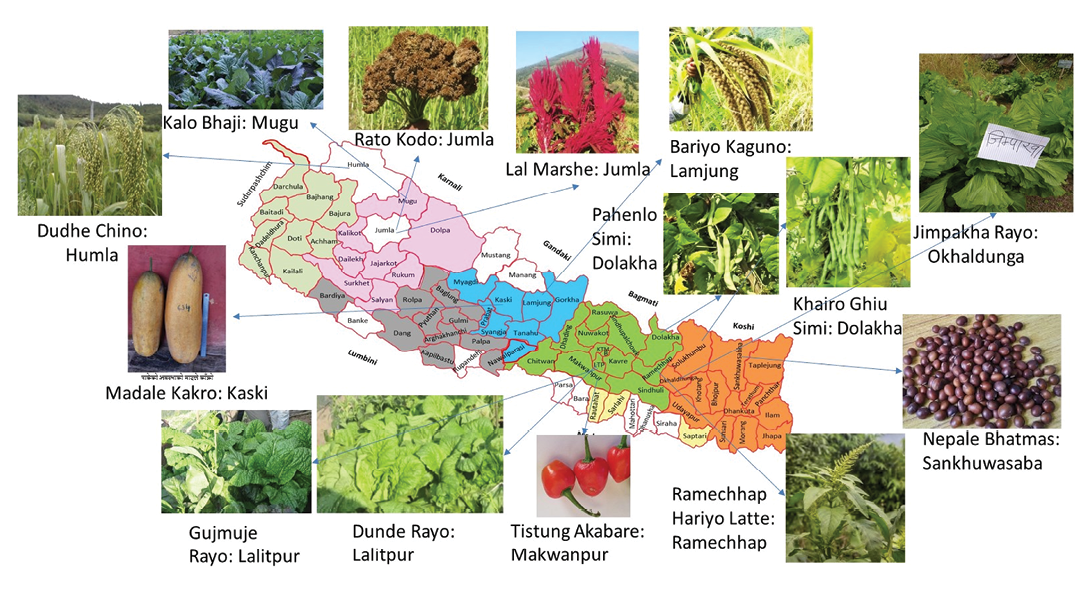

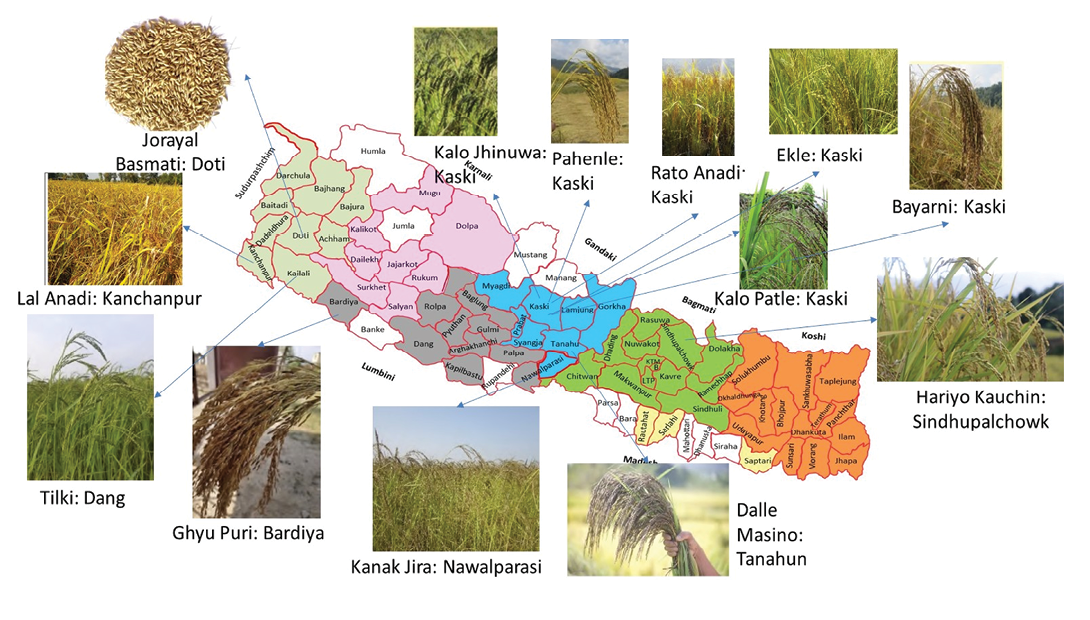

The farmers’ variety registration system in Nepal has been gaining momentum, with increasing participation from farming communities. Between 2014 and 2024, farmers from 11 districts successfully registered 14 landraces of 10 different crops, excluding rice (Figure 2) (SQCC, 2024). Additionally, 13 rice landraces from 8 districts have been formally registered in the NSB (Figure 3). Encouraged by these successes, many farmers across the country are now expressing interest in registering their local varieties, recognizing the economic, nutritional and cultural benefits associated with their conservation and commercialization. Landraces are widely valued for their purity, quality, taste, nutrition, and health benefits (Gauchan et al, 2020a; Joshi et al, 2017a). Recognizing these advantages, registration has been promoted as a good conservation practice to ensure that farmers continue using, preserving and improving their traditional seed varieties. This approach aligns with the broader strategy of "conservation through use," which encourages sustainable management of agrobiodiversity (Joshi et al, 2020a; 2020c).

Figure 2. Registered landraces other than rice crops by communities. Source: Joshi et al, 2017a; SQCC, 2024.

Several institutions are actively engaged in supporting and strengthening the registration system. Key stakeholders such as Nepal Genebank, LI-BIRD, the Department of Agriculture (DoA), SAHAS-Nepal, CSBs and community genebanks are working collaboratively on various initiatives. These organizations are facilitating capacity enhancement programmes and regular interaction sessions focusing on the importance of native landraces, the registration process, and the legal aspects of Plant Variety Protection (PVP) and Farmers’ Rights (FR). Additionally, access and benefit-sharing (ABS) mechanisms for AGRs are being developed, along with the promotion of 101 good conservation practices (Joshi et al, 2020a; 2020c). For the first time in Nepal, two legal definitions have been introduced to distinguish between native (indigenous) and local landraces (MoALD, 2024). This marks a significant milestone in seed policy, as it provides a clear framework for their identification, protection and promotion. Concurrently, various scientific studies, including collection, characterization, evaluation and DNA analysis, are being conducted to document farmers' varieties for potential geographical indication (GI) certification (Joshi et al, 2017a; Bajracharya et al, 2012; Gauchan et al, 2020a; Joshi, 2017). GI is very important for community to gain monetary benefit, which ultimately promotes native and localized landraces.

Figure 3. Registered rice landraces by communities. Source: SQCC, 2024; Joshi et al, 2017a.

The development and enhancement of farmers’ varieties is being actively pursued through participatory landrace enhancement (PLE) and participatory plant breeding (PPB), with a focus on site-specific variety development tailored to local agroecological conditions. Through PPB, farmers can develop new varieties which can be registered with support from relevant organizations. Advanced DNA fingerprinting, tissue banking, and genetic diversity assessments are also ongoing to further document and preserve Nepal’s rich agrobiodiversity. Beyond registration, a variety of community-led conservation activities are regularly organized by Nepal Genebank, LI-BIRD, the Department of Agriculture and some municipalities (Joshi et al, 2020b). These include diversity blocks, diversity fairs, diversity field schools and repatriation programmes aimed at promoting traditional varieties and reintroducing lost landraces to their places of origin (Joshi et al, 2020a). Additionally, market-linkage strategies, such as the promotion of Haat Bazaars (local markets), collection centres, homestays, and product diversification initiatives, are being implemented to strengthen the connection between primary producers and primary consumers.

Impact of farmers’ variety registration

The registration of farmers’ varieties has had a transformative impact on Nepal’s seed system, agricultural biodiversity and farming communities. One of the most significant outcomes is the conservation of site-specific varieties and genetic diversity, ensuring that traditional landraces are preserved in their natural agroecological zones. This has strengthened on-farm conservation, allowing farmers to maintain and improve their varieties while continuing traditional seed-saving practices (Joshi and Witcombe, 2003; Shrestha and Rana, 2018; Joshi et al, 2020b).

Farmers' dependency on external seed sources has been eliminated, as seed cycles are now entirely managed by farmers themselves (MoALD, 2024) for these varieties. With this shift, farmers have reclaimed their seed sovereignty, reinforcing their rights over seed production, selection and distribution. As a result, they are no longer reliant on commercial seed companies or government agencies for seed supply, ensuring greater self-sufficiency and sustainability in their farming practices (Gurung et al, 2020).

The ability to sell seeds formally has provided economic benefits to farming communities. With registered varieties, farmers can legally market their seeds, opening up new income opportunities. This has empowered smallholder farmers, many of whom previously engaged in informal seed exchanges without financial returns. Additionally, the recognition of farmers' varieties under the formal system has made them eligible for government incentives and support programmes (Gauchan et al, 2017).

Capacity building has been a crucial outcome of the registration process. Farmers have enhanced their skills in seed production, maintenance, labelling, marketing, and managing varietal diversity. This has led to better seed quality, improved market access and stronger value chains for traditional seeds. Moreover, the collaboration between farmers and plant breeders has been strengthened, fostering knowledge exchange and participatory breeding initiatives. This partnership ensures that both traditional knowledge and modern scientific approaches contribute to the development of climate-resilient, high-performing varieties (Sthapit et al, 1998; Joshi et al, 2017b).

Future directions and recommendation

Despite progress in registering farmers’ varieties in Nepal, several challenges hinder their adoption and recognition in the formal seed system. Many agriculturists and policymakers believe these varieties cannot meet national demand. Their high genetic diversity, while resilient, complicates identification, monitoring and mechanization, limiting large-scale commercial use. Farmers have faced difficulties maintaining seed quality and adhering to standard practices. CSBs often struggle to market seeds, and farmers may lack the confidence or technical knowledge to defend their varieties during registration. The absence of incentives – such as financial support, price premiums or preferential treatment – along with registration costs and long-term maintenance requirements, discourages participation. The focus of national extension programmes on hybrid seeds further limits opportunities for traditional varieties. Additionally, unclear legal frameworks (for example lack of farmers’ rights) around ownership rights create uncertainty about farmers’ control over their genetic resources. Overcoming these barriers requires stronger policy support, financial incentives and legal clarity to ensure farmers’ varieties are registered, protected, promoted and widely adopted.

The future of farmers’ variety registration in Nepal should be shaped by scientific advancements, policy reforms, and farmer-centric approaches to ensure recognition, conservation and commercialization of traditional varieties. To achieve this, the registration system must evolve to become more inclusive, decentralize, and supportive of farmers' rights. One of the key reforms should be the provision of population registration for highly heterogeneous traditional mixtures, evolutionary population and component registration of mixtures as is done in inbred lines of F1 hybrids. This would allow for greater flexibility in recognizing diverse seed populations that do not fit within conventional registration criteria. Additionally, the registration process should be decentralized, allowing both local and provincial-level authorities to facilitate the process, making it more accessible to smallholder farmers.

To protect Nepal’s rich seed heritage, GI rights should be established for many farmers’ varieties and their value-added products (Joshi et al, 2017a). Many traditional landraces hold unique characteristics tied to specific regions, making them eligible for GI branding and marketing, which could enhance their economic value (Joshi, 2017; Shrestha and Rana, 2018). Furthermore, the PVP and FR framework should be adopted nationwide to safeguard farmers' traditional knowledge, breeding efforts and seed sovereignty. Establishing a clear ABS mechanism for AGRs will also be crucial in ensuring that farmers receive fair compensation for their contributions to biodiversity conservation and seed development (Gauchan et al, 2018).

The enhancement and conservation of landraces should be approached through site-specific breeding and value addition, considering the unique agroecological and household-specific requirements of farmers (Joshi et al, 2020c; 2023a). Many traditional varieties have proven to be superior in ecological yield and food health index (FHI) compared to modern improved varieties. Since farmers are well aware of the taste, nutritional benefits, and medicinal properties of their varieties, integrating FHI-based evaluation into mainstream seed selection will further strengthen the promotion and utilization of farmers' varieties. Another critical area of focus should be seed storage. Modern agriculture has shifted towards plastic-based seed storage, which may not always be environmentally sustainable or suitable for long-term seed viability. Traditional nature-positive storage methods, such as those made from clay, wood, bamboo, leaves, bark and fruit-based materials, should be encouraged, as they align better with farmers’ seasonal storage practices while supporting environmental sustainability.

A localized seed system with a global market approach should be adopted to ensure farmers maintain control over their seeds while expanding opportunities for commercialization (Joshi et al, 2020a). Farmers should be allowed to market native and local varieties without mandatory registration, as these varieties should automatically qualify for government incentives, legal benefits, and services. Furthermore, landraces should be recognized as private goods rather than public goods, since individual households have preserved unique seed lines over generations.

The integration of advanced scientific tools such as phenomics, genomics and foodomics will enhance the study and improvement of farmers’ varieties. Gene tagging and mapping should be applied to document and utilize key genetic traits, ensuring the conservation and sustainable use of these valuable genetic resources. Additionally, a searchable online database should be developed to systematically document Nepal’s registered and native farmers’ varieties, making information more accessible to farmers, researchers and policymakers.

Lastly, the scope of variety registration should be expanded to include other crops such as fruits, forages, medicinal plants and other AGRs. Many of these crops hold significant economic, medicinal and cultural value, making their conservation and formal recognition equally important. So far, registration of farmers’ varieties has been only on orthodox seed, and due attention should also be given to non-orthodox crops (Pokhrel et al, 2017; SQCC, 2024). By adopting a multi-dimensional approach that integrates traditional knowledge with modern science, Nepal can create a more inclusive, farmer-friendly and scientifically robust farmers’ variety registration system.

Conclusion

The registration of farmers’ varieties in Nepal marks a significant step towards recognizing and formalizing traditional seed systems. Historically, the DUS system has been the foundation for variety registration, primarily to simplify identification and monitoring. However, this approach has often excluded farmers’ varieties, which naturally exhibit higher genetic diversity and adaptability. Nepal’s formal seed system gradually separated seed production from farming communities, leading to increased dependency on external entities for seed supply. This detachment marginalized farmers’ traditional seed systems, preventing their varieties from entering the formal market and making them ineligible for incentives, benefits and government support. However, with the introduction of farmers' variety registration, a shift has occurred – allowing farming communities to formally register, produce and market their own seeds, thereby re-establishing their role in the seed production cycle. This has also led to the legal recognition of genetic diversity within traditional varieties, promoting agrobiodiversity conservation through policy support.

Despite this progress, challenges remain. The current registration system still struggles to accommodate highly heterogeneous varieties and mixtures of multiple landraces. To address this, a policy shift is necessary – where native and local varieties should be automatically eligible for formal marketing, incentives and other legal benefits without requiring extensive bureaucratic approval. Moving forward, the formal seed system should focus more on value-added products, rather than strictly controlling seed production. By doing so, Nepal can adopt a localized seed system with a globalized product approach, ensuring that farmers maintain seed sovereignty while expanding market opportunities. A balanced approach that integrates both formal and informal seed systems will be key to sustainable agriculture, biodiversity conservation and farmers’ economic empowerment in Nepal.

Acknowledgements

We express our sincere gratitude to the Nepal Agricultural Research Council (NARC), Nepal Genebank, Seed Quality Control Centre (SQCC), Local Initiatives for Biodiversity, Research, and Development (LI-BIRD), Bioversity International, and SAHAS Nepal for their invaluable support and collaboration in organizing various programmes and action research initiatives. We extend our heartfelt appreciation to the Community Seed Banks (CSBs), the Community Seed Bank Association of Nepal, and the dedicated farmers who have actively contributed to the registration of their landraces, the maintenance of crop biodiversity, and their enthusiastic participation in the preparation of guidelines, training session, and participatory on-farm research.

Special acknowledgment goes to the farmers and the CSB in Dalchoki for their commendable efforts and commitment in generating critical evidence through on-farm trials, which have significantly contributed to the success of our research. We also wish to convey our deep gratitude to Madan Raj Bhatta (NAGRC), Madan Thapa (SQCC), Devendra Gauchan, and Mohan Hamal for fostering a supportive environment and taking meaningful action in advancing our shared goals.

The following projects provided financial support for this work. 1. Strengthening the scientific basis of in-situ conservation of agrobiodiversity on farm in Nepal, 1997 (in-situ global project funded by IPGRI), 2. Genetic Resources Policy Initiative (GRPI), 2003 and 2007, funded by IPGRI, 3. Strengthening National Capacities to Implement the International Treaty on Plant Genetic Resources for Food and Agriculture, 2012 (GRPI-2), funded by Bioversity International, 4. Improving seed systems for smallholder farmers’ food security, i: 2013 to 2016, and ii. 2017-2021 (Seed project), 119HQ177, funded by SDC via Bioversity International, 5. Integrating traditional crop genetic diversity into technology: Using a biodiversity portfolio approach to buffer against unpredictable environmental change in the Nepal Himalayas, 2014-2020, funded by UNEP-GEF through Bioversity International, 6. Use of genetic diversity and evolutionary plant breeding for enhanced farmer resilience to climate change, sustainable crop productivity, and nutrition under rainfed conditions, 2019-2022 (EPB), A1341 funded by IFAD through Bioversity International.

Author contributions

BK Joshi: conceptualization, data collections, field experiments, field visits, interactions, writing – original, research, methodology, and editing. P Thapa: literature review, secondary data collection, focus group discussion, editing and updating information. B Prasai: literature review, policy analysis, editing and updating information. DR Bhandari: documentation of history, gap analysis, policy analysis, editing and updating information.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

Ethics statement

Stakeholder engagement was conducted respectfully and inclusively, and all data were used solely for research purposes in line with relevant institutional and national ethical guidelines.

References

Bajracharya, J., Brown, A. H. D., Joshi, B. K., Panday, D., Baniya, B. K., Sthapit, B. R., and Jarvis, D. I. (2012). Traditional seed management and genetic diversity in barley varieties in high-hill agro-ecosystems of Nepal. Genetic Resources and Crop Evolution, 59(3), 389–398. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10722-011-9689-2

Bhandari, B., Joshi, B. K., Shrestha, P., Sthapit, S., Chaudhary, P., and Acharya, A. K. (2017). Custodian farmers, agrobiodiversity-rich areas, and agrobiodiversity conservation initiatives at grassroots levels in Nepal. In B. K. Joshi, H. B. K. C., and A. K. Acharya (Eds.), Conservation and utilization of agricultural plant genetic resources in Nepal: Proceedings of the 2nd National Workshop, 22-23 May 2017, Dhulikhel (pp. 92–101). NAGRC, FDD, DoA, and MoAD. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/348049968_Conservation_and_Utilization_of_Agricultural_Plant_Genetic_Resources_in_Nepal_Proceedings_of_2nd_National_Workshop

Chaudhary, P., Joshi, B. K., Thapa, K., Devkota, R., Ghimire, K. H., Khadka, K., Upadhya, D., and Vernooy, R. (2016). Interdependence on plant genetic resources in light of climate change. In B. K. Joshi, P. Chaudhary, D. Upadhya, and R. Vernooy (Eds.), Implementing the International Treaty on Plant Genetic Resources for Food and Agriculture in Nepal: Achievements and challenges (pp. 65–80). LIBIRD, NARC, MoAD, and Bioversity International. https://hdl.handle.net/10568/78421

De Jonge, B., Dey, B., and Visser, B. (2025). Developing a registration system for farmers' varieties. Agricultural Systems, 222, 104183. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.agsy.2024.104183

Gauchan, D., Joshi, B. K., and Bhandari, B. (2018). Farmers’ rights and access and benefit-sharing mechanisms in community seed banks in Nepal. In B. K. Joshi, P. Shrestha, D. Gauchan, and R. Vernooy (Eds.), Community seed banks in Nepal: 2nd National Workshop Proceedings, 3-5 May 2018, Kathmandu, Nepal (pp. 117–132). NAGRC, LI-BIRD, and Bioversity International. https://hdl.handle.net/10568/99141

Gauchan, D., Joshi, B. K., Bhandari, B., Ghimire, K. H., Pant, S., Gurung, R., Pudasaini, N., Paneru, P. B., Mishra, K. K., and Jarvis, D. I. (2020a). Value chain development and mainstreaming of traditional crops for nutrition-sensitive agriculture in Nepal. In D. Gauchan, B. K. Joshi, B. Bhandari, H. K. Manandhar, and D. Jarvis (Eds.), Traditional crop biodiversity for mountain food and nutrition security in Nepal: Tools and research results of the UNEP GEF Local Crop Project, Nepal (pp. 174–182). NAGRC, LI-BIRD, and the Alliance of Bioversity International and CIAT. https://himalayancrops.org/project/traditional-crop-biodiversity-for-mountain-food-and-nutrition-security-in-nepal/

Gauchan, D., Joshi, B. K., Sthapit, S., and Jarvis, D. (2020b). Traditional crops for household food security and factors associated with on-farm crop diversity in the mountains of Nepal. The Journal of Agriculture and Environment, 21, 31–43. https://hdl.handle.net/10568/109041

Gauchan, D., Joshi, B. K., Sthapit, S., Ghimire, K., Gautam, S., Poudel, K., Sapkota, S., Neupane, S., Sthapit, B., and Vernooy, R. (2016). Post-disaster revival of the local seed system and climate change adaptation: A case study of earthquake-affected mountain regions of Nepal. Indian Journal of Plant Genetic Resources, 29(3), 119–119.

Gauchan, D., Tiwari, S. B., Acharya, A. K., Pandey, K. R., and Joshi, B. K. (2017). National and international policies and incentives for agrobiodiversity conservation and use in Nepal. In B. K. Joshi, H. B. K. C., and A. K. Acharya (Eds.), Conservation and utilization of agricultural plant genetic resources in Nepal: Proceedings of the 2nd National Workshop, 22-23 May 2017, Dhulikhel (pp. 176–183). NAGRC, FDD, DoA, and MoAD. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/348049968_Conservation_and_Utilization_of_Agricultural_Plant_Genetic_Resources_in_Nepal_Proceedings_of_2nd_National_Workshop

Gurung, R., Pudasaini, N., Sthapit, S., Palikhey, E., and Gauchan, D. (2020). Seed system of traditional crops in the mountains of Nepal. In D. Gauchan, B. K. Joshi, B. Bhandari, H. K. Manandhar, and D. I. Jarvis (Eds.), Traditional crop biodiversity for mountain food and nutrition security in Nepal: Tools and research results of UNEP GEF Local Crop Project, Nepal (pp. 108–115). NAGRC, LI-BIRD, and the Alliance of Bioversity International and CIAT. http://himalayancrops.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/Traditional-Crop-Biodiversity-for-Mountain-Food-and-Nutrition-Security-in-Nepal.pdf

Gurung, R., Dhakal, R., Pudasaini, N., Paneru, P.B., Pant, S., Adhikari, A.R., Gautam, S., Yadav, R.K., Ghimire, K.H., Joshi, B.K., Gauchan, D., Shrestha, S., and Jarvis, D.I. (2019). Catalog of Traditional Crop Landraces of Mountain Agriculture in Nepal. LI-BIRD, Pokhara; NARC, Kathmandu and Bioversity International, Nepal. http://himalayancrops.org/project/catalogue-of-traditional-mountain-crop-landraces-in-nepal/

Joshi, B.K., Gurung, S.B., Mahat, P.M., Bhandari, B. and Gauchan, D. (2018). Intra-Varietal Diversity in Landrace and Modern Variety of Rice and Buckwheat. The Journal of Agriculture and Development, 19, 1-8. https://hdl.handle.net/10568/97576

Joshi, B. K. (2017). Plant breeding in Nepal: Past, present, and future. Journal of Agriculture and Forestry University, 1, 1–33. http://afu.edu.np/sites/default/files/Plant_breeding_in_Nepal_Past_Present_and_Future_BK_Joshi.pdf

Joshi, B. K., Acharya, A. K., Gauchan, D., Singh, D., Ghimire, K. H., and Sthapit, B. R. (2017a). Geographical indication: A tool for supporting on-farm conservation of crop landraces and for rural development. In B. K. Joshi, H. B. K. C., and A. K. Acharya (Eds.), Conservation and utilization of agricultural plant genetic resources in Nepal: Proceedings of the 2nd National Workshop, 22-23 May 2017, Dhulikhel (pp. 50–62). NAGRC, FDD, DoA, and MoAD. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/348049968_Conservation_and_Utilization_of_Agricultural_Plant_Genetic_Resources_in_Nepal_Proceedings_of_2nd_National_Workshop

Joshi, B. K., Bhatta, M. R., Ghimire, K. H., Khanal, M., Gurung, S. B., Dhakal, R., and Sthapit, B. R. (2017b). Released and promising crop varieties of mountain agriculture in Nepal (1959-2016). LI-BIRD, Pokhara; NARC, Kathmandu; and Bioversity International. https://hdl.handle.net/10568/80892

Joshi, B. K., Gauchan, D., Bhandari, B., and Jarvis, D. (Eds.). (2020a). Good practices for agrobiodiversity management. NAGRC, LI-BIRD, and Alliance of Bioversity International and CIAT. https://hdl.handle.net/10568/109625

Joshi, B. K., Ghimire, K. H., Neupane, S. P., Gauchan, D., and Mengistu, D. K. (2023a). Approaches and advantages of increased crop genetic diversity in the fields. Diversity, 15(603). https://doi.org/10.3390/d15050603

Joshi, B. K., Gorkhali, N. A., Pradhan, N., Ghimire, K. H., Gotame, T. P., K. C., P., Mainali, R. P., Karkee, A., and Paneru, R. B. (2020b). Agrobiodiversity and its conservation in Nepal. Journal of Nepal Agricultural Research Council, 6, 14–33. https://doi.org/10.3126/jnarc.v6i0.28111

Joshi, B. K., Humagain, R., Dhakal, L. K., and Gauchan, D. (2020c). Integrated approach of national seed systems for assuring improved seeds to smallholder farmers in Nepal. In R. B. Shrestha, M. E. Penunia, and M. Asim (Eds.), Strengthening seed systems – Promoting community-based seed systems for biodiversity conservation and food and nutrition security in South Asia (pp. 181–194). SAARC Agriculture Center, Bangladesh; Asian Farmers’ Association, the Philippines; and Pakistan Agricultural Research Council, Pakistan. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/342491585_Integrated_Approach_of_National_Seed_Systems_for_Assuring_Improved_Seeds_to_the_Smallholder_Farmers_in_Nepal

Joshi, B.K., Ojha, P., Gauchan, D., Ghimire, K.H., Bhandari, B. and KC, H.B. (2020d). Nutritionally unique native crop landraces from mountain Nepal for geographical indication right. In D. Gauchan, B.K. Joshi, B. Bhandari, H.K. Manandhar and D. Jarvis (Eds.), Traditional Crop Biodiversity for Mountain Food and Nutrition Security in Nepal . Tools and Research Results of the UNEP GEF Local Crop Project, Nepal (pp. 87-99). NAGRC, LI-BIRD and the Alliance of Bioversity International and CIAT; Kathmandu, Nepal. https://himalayancrops.org/project/traditional-crop-biodiversity-for-mountain-food-and-nutrition-security-in-nepal/

Joshi, B.K., Gauchan, D., Ghimire, K.H. and Ayer, D.K. (2022). Five-cell Analysis (FCA). In B.K. Joshi, D. Gauchan and .D.K Ayer (Eds.), Participatory agrobiodiversity tools and methodologies (PATaM) in Nepal, (pp. 24-25). NAGRC, LI-BIRD, and Alliance of Bioversity International and CIAT; Kathmandu, Nepal. https://api.giwms.gov.np/storage/75/posts/1685027635_2.pdf

Joshi, K. D., and Witcombe, J. (2003). The impact of participatory plant breeding (PPB) on landrace diversity: A case study for high-altitude rice in Nepal. Euphytica, 134, 117–125. doi: https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1026151017274

Karkee, A., Magar, P. B., Thapa, P., Mainali, R. P., Ghimire, K. H., Joshi, B. K., and Bhattarai, M. (2023). Evaluation of barley landraces for yellow rust disease resistance along with grain yield. In Proceedings of the 32nd National Winter Crops Workshop, 31 May–2 June 2022, Lumle, NARC (pp. 429–439). https://www.researchgate.net/publication/367074827

LI-BIRD and The Development Fund. (2017). Farmers’ seed systems in Nepal: Review of national legislations. Pokhara, Nepal. https://libird.org/farmers-seed-system-in-nepal-review-of-national-legislations/

Ministry of Agricultural Development (MoAD). (2013). Seed Regulation-2013. Ministry of Agricultural Development, Government of Nepal, Kathmandu, Nepal. (In Nepali).

Ministry of Agriculture (MoA). (1997). The Seeds Regulation-1997. Ministry of Agriculture, His Majesty’s Government, Nepal. (In Nepali).

Ministry of Agriculture and Livestock Development (MoALD). (2022). Seed Act-1988 (2nd amendment). Ministry of Agriculture and Livestock Development, Government of Nepal, Kathmandu, Nepal. (In Nepali).

Ministry of Agriculture and Livestock Development (MoALD). (2024). Seed Regulation. Ministry of Agriculture and Livestock Development, Government of Nepal, Kathmandu, Nepal. (In Nepali).

NAGRC. 2024. Annual Report 2080/81 (2023/24). National Agriculture Genetic Resources Centre, NARC, Khumaltar, Lalitpur, Nepal.

Neupane, S.P., Joshi, B.K., Aair, D., Ghimire, K.H., Gauchan, D., Karkee, A., Jarvis, D.I., Mengistu, D.K., Grando, S., and Ceccarell, S. (2023). Farmers’ preferences and agronomic evaluation of dynamic mixtures of rice and bean in Nepal. Diversity, 15, 660. https://doi.org/10.3390/d15050660

Pokhrel, S., Joshi, B. K., Gauchan, D., and Acharya, A. K. (2017). Utilization of agricultural plant genetic resources in research, breeding, production, nutrition, and distribution. In B. K. Joshi, H. B. K. C., and A. K. Acharya (Eds.), Conservation and utilization of agricultural plant genetic resources in Nepal: Proceedings of the 2nd National Workshop, 22-23 May 2017, Dhulikhel (pp. 39–49). NAGRC, FDD, DoA, and MoAD, Kathmandu, Nepal. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/348049968_Conservation_and_Utilization_of_Agricultural_Plant_Genetic_Resources_in_Nepal_Proceedings_of_2nd_National_Workshop

Poudel, D., Sthapit, B., and Shrestha, P. (2015). An analysis of social seed network and its contribution to on-farm conservation of crop genetic diversity in Nepal. International Journal of Biodiversity, 2015, Article ID 312621. https://doi.org/10.1155/2015/312621

Shrestha, P., and Rana, R. B. (2018). Community seed banks in Nepal: Safeguarding agricultural biodiversity and strengthening local seed systems. In B. K. Joshi, P. Shrestha, D. Gauchan, and R. Vernooy (Eds.), Community seed banks in Nepal: 2nd National Workshop proceedings, 3–5 May 2018, Kathmandu, Nepal (pp. 45–67). NAGRC, LI-BIRD, and Bioversity International. https://hdl.handle.net/10568/99141

Shrestha, P., Sthapit, S., and Paudel, I. (2013). Community seed banks: A local solution to increase access to quality and diversity of seeds. In P. Shrestha, R. Vernooy, and P. Chaudhary (Eds.), Community seed banks in Nepal: Past, present, future. Proceedings of a national workshop (pp. 61–75). LI-BIRD/USC Canada Asia/Oxfam/The Development Fund/IFAD/Bioversity International. https://hdl.handle.net/10568/68933

SQCC. 2024. Notified or denotified varieties updated 2081-07-23. Seed Quality Control Center, MoALD, Kathmanud, Nepal (in Nepali language).

Sthapit, B. (2013). Emerging theory and practice: Community seed banks, seed system resilience, and food security. In P. Shrestha, R. Vernooy, and P. Chaudhary (Eds.), Community seed banks in Nepal: Past, present, future. Proceedings of a national workshop (pp. 16–40). LI-BIRD/USC Canada Asia/Oxfam/The Development Fund/IFAD/Bioversity International. https://hdl.handle.net/10568/68933

Sthapit, B., and Jarvis, D. (2003). Implementation of on-farm conservation in Nepal. In D. Gauchan, B. R. Sthapit, and D. I. Jarvis (Eds.), Agrobiodiversity conservation on-farm: Nepal's contribution to a scientific basis for national policy recommendations (pp. 8–12). IPGRI. https://hdl.handle.net/10568/105239

Sthapit, B., Gauchan, D., Sthapit, S., Ghimire, K. H., Joshi, B. K., De Santis, P., and Jarvis, D. (2019). Sourcing and deploying new crop varieties in mountain production systems. In O. T. Westengen and T. Winge (Eds.), Farmers and plant breeding: Current approaches and perspectives (pp. 196–216). Routledge. https://hdl.handle.net/10568/105452

Sthapit, B., Joshi, K., Rana, R., and Subedi, A. (1998). Spread of varieties from participatory plant breeding in the high altitude villages of Nepal. LI-BIRD Technical Report Series. LI-BIRD. https://libird.org/spread-of-varieties-from-participatory-plant-breeding-in-high-altitude-villages-of-nepal/

Subedi, A., Devkota, R., Paudel, I. P., and Subedi, S. (2013). Community biodiversity registers in Nepal: Enhancing the capabilities of communities to document, monitor, and take control over their genetic resources. In W. S. de Boef, N. Peroni, A. Subedi, M. H. Thijssen, and E. O'Keeffe (Eds.), Community biodiversity management: Promoting resilience and the conservation of plant genetic resources (pp. 177–188). Earthscan and Bioversity International. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203130599

Subedi, A., Sthapit, B., Shrestha, P., Gauchan, D., and Upadhyay, M. (2005). Emerging methodology of community biodiversity register: A synthesis. In A. Subedi, B. R. Sthapit, M. P. Upadhyay, and D. Gauchan (Eds.), Learning from community biodiversity register in Nepal: Proceedings of the national workshop, 27–28 October 2005, Khumaltar, Nepal (pp. 75–83). https://idl-bnc-idrc.dspacedirect.org/bitstreams/4cbf2874-f54e-4307-96f7-cd52393ad51d/download

Thapa, M., Sapkota, D., and Joshi, B. K. (2019). Crop groups based on national list: Released, registered, denotified, formal, and informal. In B. K. Joshi and R. Shrestha (Eds.), Proceedings of the national workshop of the working groups of agricultural plant genetic resources (APGRs), 21–22 June 2018 (pp. 36–44). NAGRC, Kathmandu, Nepal. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/334400726_crop_group_based_on_national_list_released_registered_de-notified_formal_and_informal

Upreti, B. R., and Upreti, Y. G. (2002). Factors leading to agro-biodiversity loss in developing countries: The case of Nepal. Biodiversity and Conservation, 11(8), 1607–1621. Doi: https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1016862200156

Zhu, Y., Chen, H., Fan, J., Wang, Y., Li, Q., Chen, J., Fan, J., Yang, S., Hu, L., Leunak, H., Mewk, T.W., Tengk, P.S., Wanak, Z. and Mundt, C.C. (2000). Genetic diversity and disease control in Rice. Nature, 406, 718-722.