Current status of the diversity and conservation of genetic resources of Capsicum spp. (chilli pepper) in Oaxaca, Mexico

Yeimy Clemencia Ramirez-Rodas*, Luis Yobani Gayosso-Rosales and Ulises Santiago-López

Instituto Nacional de Investigaciones Forestales, Agrícolas y Pecuarias. C.E. Valles Centrales, C. Melchor Ocampo 7, Sto. Domingo Barrio Bajo, Etla, Oaxaca, México. C.P. 68200

* Corresponding authors: Yeimy Clemencia Ramirez-Rodas (ramirez.yeimy@inifap.gob.mx)

Abstract: Oaxaca, Mexico, has a wide diversity of genetic resources of Capsicum spp. (chilli pepper), with at least 25 of the 90 chilli pepper types reported for Mexico. However, some have stopped being cultivated, making it necessary to conduct an updated diagnosis to implement conservation and sustainable use practices. The objective of this work was to describe the current situation of chilli pepper crop biodiversity in the state of Oaxaca, Mexico, and identify how they are conserved. The study identified that the most important chilli peppers for production or cultural uses in Oaxaca are: Agua, Costeño, Soledad, Tabaquero, Taviche, and Huacle, as well as less utilized varieties, including domesticated, semi-wild or wild varieties that are part of the state’s cultural identity and diversity. Currently, seed collections of native chilli peppers are conserved ex situ in three seedbanks in Mexico, and they are also cultivated (in situ) by farmers, often in backyards, or left uncultivated (semi-wild or wild).

Keywords: Agrobiodiversity, native plant, conservation of chilli pepper

Introduction

The genus Capsicum (chilli pepper) belongs to the Solanaceae family. This genus includes five domesticated species: Capsicum chinense Jacq., Capsicum frutescens L., Capsicum baccatum L., Capsicum pubescens Ruiz & Pav., and Capsicum annuum L., the latter encompassing most of the chilli varieties in Mexico and being the most agriculturally and economically important (Pickersgill, 2016). The use and cultivation of C. annuum have a long cultural history in Mexico (Pérez-Martínez et al, 2022). In every culture within the multiethnic territory, chilli is a central ingredient in daily cuisine, forming part of national identity (Ruiz-Núñez et al, 2018). Around 90 types of chilli are known in Mexico (Aguilar-Meléndez and Lira-Noriega, 2018), with the greatest diversity found in the southern states, especially Oaxaca, which harbours at least 25 types (Aguilar-Rincón et al, 2010). Despite their agricultural, economic, cultural and gastronomic significance, these plant genetic resources are threatened by genetic erosion, and some types have ceased to be cultivated (Rodríguez-Campos, 2018). In fact, some farmers in Oaxaca report that certain chilli types are no longer grown due to pests, diseases, replacement by commercial varieties and water scarcity, among other factors (Aguilar-Rincón et al, 2010). In addition, local species are often limited by the agroecological characteristics of their environment and generally remain within their natural distribution areas (Guzmán-Mendoza et al, 2022). In this regard, genetic resources, including plant species, are of great importance in food production and food security. Food security, from an agricultural perspective, refers to the conservation and use of biological diversity through the capacity to produce more sustainable food. This includes the use of genetic resources as raw material for genetic improvement, which involves the selection of local varieties or the development of new varieties that are more tolerant to drought, pests, diseases or poor soils; the selection of plant varieties with higher yield and nutritional quality; and local or improved varieties that require fewer fertilizers or pesticides (FAO, 2012). The objective of this work was to describe the current situation of chilli pepper biodiversity in the state of Oaxaca, Mexico, and to identify how it is conserved to gain a perspective for implementing exploration, conservation and use of chilli germplasm.

Chilli pepper diversity in the state of Oaxaca

Oaxaca is the Mexican state with the greatest diversity of chilli peppers, including C. annuum var. annuum (domesticated and semi-domesticated): Mirador, Nanche, Soltero, Güiña Shirundu, Mirasol, Tusta, Güiña Shuladi, Solterito, Loco, Pasilla Oaxaca (Pasilla Mixe), Costeño, Escuchito, Achilito, Huacle, Tabaquero (Chiltepe), Coxle, de Monte, Soledad, Taviche, de Onza, and de Agua; C. annuum var. acuminatum Fingerth: chile Chocolate; C. annuum var. glabriusculum (Dunal) Heiser & Pickersgill: chile Bolita and Piquín (wild relatives of domesticated varieties); and C. pubescens: Manzano (López-López and Castro-García, 2006; Aguilar-Rincón et al, 2010; Castellón-Martínez et al, 2012; Sclavo-Castillo et al, 2024). Of these, at least 44% have been identified as native to Oaxaca: Tusta, Tabaquero, Taviche, Solterito, Piquín, Nanche, Costeño, Bolita, Huacle, de Agua, and Pasilla Mixe (Vera-Guzmán et al, 2011; Castellón-Martínez et al, 2012; Martínez-Martínez et al, 2014; Sanjuan-Martínez, 2020). Despite their cultural, social, economic and culinary importance, some of these types are better known than others. For instance, the Statistical Yearbook of Agricultural Production from the SIAP platform (SIAP, 2023) only provides data for the de Agua, Costeño, Soledad, and Tabaquero chillis, in addition to commercial varieties such as Ancho, Habanero, Pasilla and Serrano. However, semi-domesticated types, generally cultivated in home gardens, and wild types of C. annuum are not included.

Moreover, the presence of the wild species Capsicum rhomboideum (Dunal) Kuntze [synonym C. ciliatum (Kunth) Kuntze] has been documented in the state of Oaxaca, mainly distributed in sub-humid zones and to a lesser extent in semi-arid and humid areas (UNAM, 2007; Aguilar-Meléndez and Lira-Noriega, 2018). These represent an important part of the genetic diversity and germplasm variability, and are deeply linked to Oaxaca’s cultural heritage. Each region in the state is associated with specific types of chilli peppers, some of which are presented in detail below.

Most relevant chilli peppers based on their production and utilization

Chile de Agua

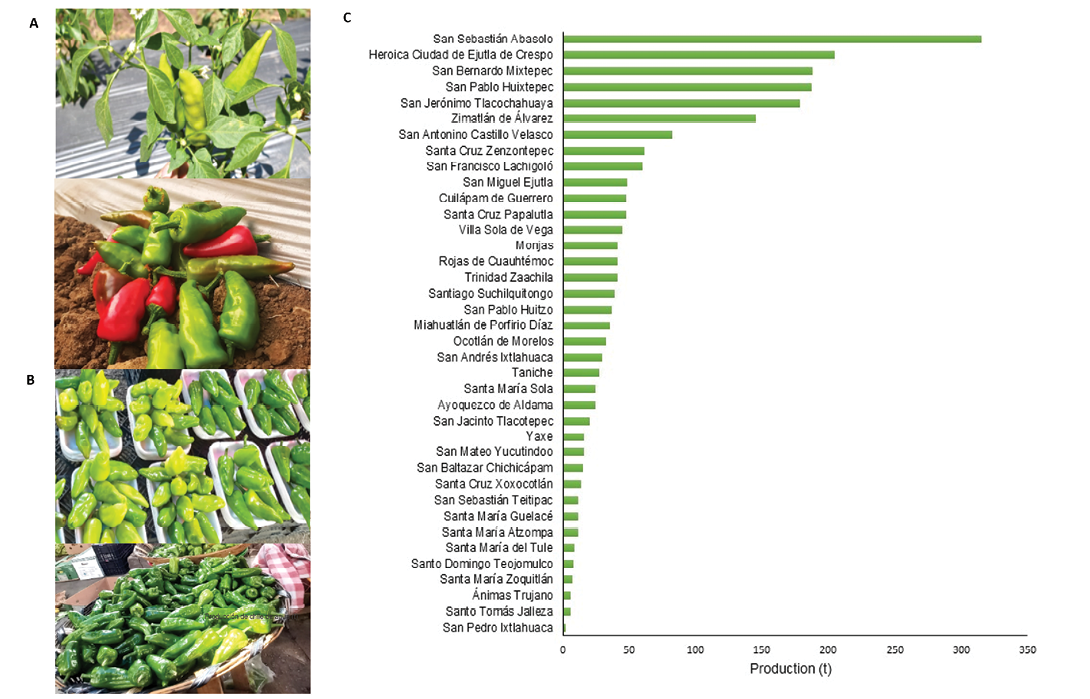

It is a native variety from the Central Valleys and is primarily cultivated in the municipalities of San Sebastián Abasolo, Heroica Ciudad de Ejutla de Crespo, San Bernardo Mixtepec, San Pablo Huixtepec, and San Jerónimo Tlacochahuaya, which together produce about 50% of the total output (Figure 1; SIAP, 2023). Geographically, it is located at 16° 59′ N and 96° 35′ W, between 1,400 and 1,700m elevation. The production cycle of this crop requires approximately 150–228 workdays per hectare (López-López and García-Castro, 2006; López-López and Rodríguez-Hernández, 2019), with one or two planting cycles. In 2023, 272 hectares were cultivated, with an average yield of 7.8t/ha (SIAP, 2023). However, a survey by Aparicio-del-Moral et al. (2013) reported yields ranging from 3.2t/ha to 5.8t/ha under open-field and gravity irrigation conditions. López-López and Rodríguez-Hernández (2019) indicate that as new technological components are introduced into the production system Feel free to change the proposed short running title as long as it stays in the 45-character (including spaces) limit Feel free to change the proposed short running title as long as it stays in the 45-character (including spaces) limit – such as artificial protection, drip fertigation and producer-selected seeds – fruit quality improves (greater proportion of first- and second-grade fruits), and yields can reach up to 16.8t/ha within a 110–122-day cycle, indicating significant opportunities for improvement.

Figure 1. Chile de Agua is a type of chilli native to the Central Valleys of Oaxaca, Mexico. A, Plant and fruits at physiological maturity; B, Fruits marketed at the Oaxaca Central Market, at horticultural maturity; C, Agricultural production (t) 2023 of chile de Agua in different municipalities in the state of Oaxaca (SIAP, 2023).

The fruits are generally marketed at their consumption maturity stage, when they still display the characteristic light green colour. They are consumed roasted, in sauces, or stuffed; used to serve beverages such as mezcal; and even employed in floral arrangements.

Currently, regarding new varieties, only one, ‘Nasha’ has been developed by the National Institute for Forestry, Agricultural and Livestock Research (INIFAP) and registered in the National Catalog of Plant Varieties with breeder title No. 2465 (SNICS, 2024).

The fruit is triangular with an erect position, light green colour, thick pericarp, pointed apex and smooth skin (López-López and García-Castro, 2006). Chile de Agua is sold locally, and the unit of measurement is known as a ‘carga’, which contains approximately 800 top-quality chillies and weighs about 60kg. Although there is no official quality standard, quality is based on consumer demands and classified into three grades according to size, colour, brightness and absence of damage:

- First grade: fruits ≥ 10cm in length and ≥ 5cm in diameter at the base, uniform green colour, no deformities, smooth and shiny pericarp, and free from insect damage, physiological disorders or pathogens

- Second grade: fruits ≤ 10cm long and ≤ 5cm in diameter, with slight reddish discolouration, smooth and shiny pericarp, may show up to 5% damage, and can have deformities.

- Third grade: all other fruits not meeting the above criteria (Virgen, 2006; Ambrosio, 2007).

Chile Costeño

It is native to Oaxaca and is mostly cultivated in the Coast region. In 2023, agricultural production in Oaxaca was 2,415t, with yields ranging from 1.8t/ha to 3.45t/ha (Table 1; SIAP, 2023). It is distributed between the coordinates 15° 54′ 00″ N and 98° 06′ 00″ W, at elevations below 500m. The fruits are triangular without a neck at the base, with a thin, slightly wrinkled pericarp and smooth skin. This chile comes in yellow and red at physiological maturity and is sold dried, with a smooth, dark red colour (López-López and García-Castro, 2006) (Figure 2). It is used in making mole, salsas and other regional dishes (Ovando, 2007).

Table 1. 2023 agricultural production of chile Costeño in the state of Oaxaca, which describes the planted and harvested area, production and yield by municipality (SIAP, 2023).

|

Municipality |

Area planted (ha) |

Area harvested (ha) |

Production (t) |

Yield (t/ha) |

|

Villa de Tututepec de Melchor Ocampo |

135.20 |

135.20 |

341.65 |

2.53 |

|

Santiago Pinotepa Nacional |

107.00 |

107.00 |

315.55 |

2.95 |

|

Tataltepec de Valdés |

125.50 |

125.50 |

297.25 |

2.37 |

|

Santiago Jamiltepec |

97.50 |

97.50 |

263.50 |

2.70 |

|

Santa María Huazolotitlán |

86.50 |

86.50 |

238.80 |

2.76 |

|

Santo Domingo Tonalá |

85.60 |

75.60 |

207.90 |

2.75 |

|

San Andrés Huaxpaltepec |

66.45 |

66.45 |

200.25 |

3.01 |

|

Santa María Zacatepec |

47.80 |

47.80 |

143.40 |

3.00 |

|

San Pedro Amuzgos |

23.70 |

23.70 |

68.75 |

2.90 |

|

Pinotepa de Don Luis |

19.50 |

19.50 |

67.30 |

3.45 |

|

Mártires de Tacubaya |

33.25 |

33.25 |

59.85 |

1.80 |

|

Santo Domingo Armenta |

27.00 |

27.00 |

56.70 |

2.10 |

|

San Antonio Tepetlapa |

22.00 |

22.00 |

39.60 |

1.80 |

|

San Sebastián Ixcapa |

17.50 |

17.50 |

37.65 |

2.15 |

|

San Lorenzo |

15.75 |

15.75 |

34.65 |

2.20 |

|

Santa María Ipalapa |

9.50 |

9.50 |

29.45 |

3.10 |

|

San Pedro Mixtepec |

4.00 |

4.00 |

12.80 |

3.20 |

|

Total |

923.75 |

913.75 |

2,415.05 |

2.64 |

Chile Soledad

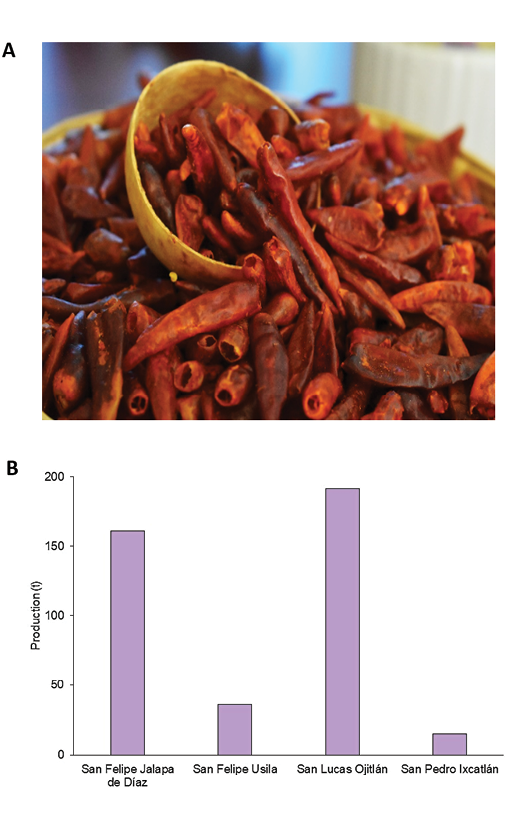

It is grown in the Papaloapan region at elevations between 100 and 400m (Aguilar-Rincón et al, 2010). It has an average production of 1,764t and a yield of 6t/ha (Table 2; SIAP, 2023). The plant grows erect with angular stems, green with purple longitudinal stripes, and dense pubescence. The calyx lacks pigmentation. The fruits are elongated, green when immature and red when mature, with smooth skin. It is cultivated in seasonal conditions (August to March) (Aguilar-Rincón et al, 2010).

Table 2. 2023 agricultural production of chile Soledad in the state of Oaxaca, which describes the planted and harvested area, production and yield by municipality of Papaloapan and Itsmo region (SIAP, 2023).

|

Region |

Municipality |

Area planted (ha) |

Area harvested (ha) |

Prodution (t) |

Yield (t/ha) |

|

Papaloapan |

San Juan Bautista Tuxtepec |

94.70 |

81.70 |

530.55 |

6.49 |

|

Papaloapan |

Loma Bonita |

53.80 |

43.80 |

338.79 |

7.73 |

|

Papaloapan |

San José Chiltepec |

26.60 |

24.60 |

183.84 |

7.47 |

|

Papaloapan |

San Lucas Ojitlán |

30.00 |

30.00 |

130.5 |

4.35 |

|

Papaloapan |

Santa María Jacatepec |

17.55 |

15.55 |

109.00 |

7.01 |

|

Papaloapan |

San Juan Cotzocón |

21.50 |

17.00 |

101.7 |

5.98 |

|

Papaloapan |

Santiago Yaveo |

23.50 |

17.50 |

101.15 |

5.78 |

|

Papaloapan |

Santiago Jocotepec |

19.30 |

19.30 |

80.95 |

4.19 |

|

Papaloapan |

San Juan Lalana |

11.20 |

11.20 |

52.66 |

4.70 |

|

Papaloapan |

Ayotzintepec |

9.30 |

9.30 |

45.47 |

4.89 |

|

Papaloapan |

San Juan Bautista Valle Nacional |

6.00 |

6.00 |

42.20 |

7.03 |

|

Istmo |

Asunción Ixtaltepec |

5.25 |

5.25 |

19.69 |

3.75 |

|

Papaloapan |

San Felipe Jalapa de Díaz |

7.00 |

7.00 |

19.60 |

2.80 |

|

Papaloapan |

San Felipe Usila |

2.00 |

2.00 |

5.50 |

2.75 |

|

Papaloapan |

San Pedro Ixcatlán |

1.20 |

1.20 |

3.18 |

2.65 |

|

Total |

328.90 |

291.40 |

1,764.78 |

6.06 |

|

Chile Tabaquero

Also known as chile Chiltepe, this variety is native to Oaxaca (Aguilar-Rincón et al, 2010; Toxqui-Tapia et al, 2022). It is currently cultivated in the Papaloapan región, with an average yield of 3.1t/ha (Figure 3). The plant is of intermediate growth, reaching 64.8 to 117cm in height, 120 days after transplanting. It yields an average of 97.8g per plant, with about 30 fruits averaging 3.3g and 3.6 to 4.79cm in length (Castellón-Martínez et al, 2014). The fruit contains higher levels of phenolic compounds (total phenols and flavonoids) when immature. It also has a low capsaicin content (6.7µg/ml) compared to other types such as piquín (116.2µg/ml), but is rich in vitamin C (Vera-Guzmán et al, 2011). It is consumed both fresh and dried and is used to make various dishes and sauces, including ‘chintextle’ (a spreadable dry chilli paste) (Aguilar-Rincón et al, 2010; Castellón-Martínez et al, 2014).

Chile Taviche

It is native to the Central Valleys of Oaxaca (Castellón-Martínez et al, 2014) and was one of the main ingredients and chillis in local dishes in Santo Domingo Tomaltepec up until around the 1950s. It is currently grown in Miahuatlán de Porfirio Díaz in the Central Valleys and the Sierra Sur region (Aguilar-Rincón et al, 2010; Sanjuan-Martínez et al, 2022; Sclavo-Castillo et al, 2024). The fruit is a triangular berry 3 to 6cm in length, mostly consumed dried to make mole and sauces known as ‘chirmoles’ (Figure 4) (Aguilar-Rincón et al, 2010). This chile is locally known but not commonly found in major Oaxaca markets. Surveys in the Benito Juárez Market, Central de Abastos in Oaxaca City, and on market days in Villa de Etla showed that vendors often confuse chile Taviche with chile Costeño, but they differ morphologically: Taviche has a distinctly triangular base. Like chile de Agua, Tusta, and Solterito, chile Taviche is favoured by consumers in the Central Valleys (Castellón-Martínez et al, 2012). The fresh fruits of Taviche are used to prepare sauce and green mole, while the dried fruits are used to make sauces for traditional dishes such as mole, coloradito and amarillo. Studies have been conducted on its plant and fruit characteristics based on samples collected from Santa Cruz Xitla, San Simón Almolongas, Miahuatlán de Porfirio Díaz, Ejutla de Crespo and San Miguel Ejutla (Castellón-Martínez et al, 2014; Sanjuan-Martínez et al, 2022).

Chile Huacle

It is native to the Sierra de Flores Magón region, located in the northwest of the state of Oaxaca. It is exclusively cultivated in this area, particularly in the municipalities of San Juan Bautista Cuicatlán and, more recently, in Santo Domingo del Chilar. The cultivated areas range from 0.5 to 1 hectare, with yields of 1t/ha of dried chilli (López-López and Pérez-Bennetts, 2015). The fruit is a trapezoidal-shaped berry with a smooth surface texture, a pointed apex, green when immature and dark brown at physiological maturity (Figure 5), in addition to yellow and red colour variants when ripe (López-López and Pérez-Bennetts, 2015; Galeote-Cid et al, 2022). It is one of the most representative chillies of Oaxaca as it is a main ingredient in the traditional ‘Mole negro Oaxaqueño’, internationally recognized and featured in the book Ark of taste of Slow Food (Slow Food, 2025); Mole negro is an emblematic dish of Oaxacan cuisine, which was declared Intangible Cultural Heritage of the State of Oaxaca by the local Congress in 2008 and is part of Mexican cuisine, recognized as one of the finest in the world by UNESCO in 2010 (UNESCO, 2010; Baez-Vera et al, 2018). This chilli is highly valued and experiences peak demand during two traditional festive seasons – Day of the Dead in November, and December holidays – when its price ranges from 800 to 1,000 Mexican pesos per kilogram. Despite its cultural importance, its use is increasingly being replaced by more commercially available and affordable chillies such as ancho and guajillo.

Lesser-used cultivated chillies

This group includes domesticated chillies with limited usage, yet they play an important role in the biodiversity of Oaxacan chillies. They are cultivated on a very local scale. Notable among them is the Pasilla Oaxaca or Pasilla Mixe, native to the Mixe region of Oaxaca and cultivated in the Central Valleys, Sierra de Flores Magón, and Sierra de Juárez (Mixe region). The plant grows to about 121cm in height, with 20 fruits per plant and a yield of 263g per plant (Sanjuan-Martínez et al, 2022). It is mainly sold dried, with fruits smoked using oak wood in traditional ovens. It is used in mole and in making a paste known as ´chintextle´ (Aguilar-Rincón et al, 2010; Sanjuan-Martínez, 2020).

Tusta is cultivated in the Central Valleys, Coast, and Sierra Sur; it is collected from backyard gardens and ‘milpas’, and also cultivated on hillsides (Aguilar-Rincón et al, 2010; Taitano et al, 2019). At 120 days after transplanting (DAT), plants measure between 46.8cm and 60.7cm in height, with an average yield of 35.2g per plant and fruit length ranging from 1.47 to 2.8cm (Aguilar-Rincón et al, 2010; Castellón-Martínez et al, 2014; Santiago-Luna et al, 2016). The fruits have a short postharvest life, losing about 20% of their weight in the first three days of storage. Average capsaicin and dihydrocapsaicin contents are 51.4µg/ml and 33.5µg/ml, respectively (Vera-Guzmán et al, 2011; Castellón-Martínez et al, 2014).

In the Sierra de Flores Magón region, in addition to Huacle chilli, local chillies such as Coxle and Achilito, endemic to the area, are grown (López-López et al, 2016), often intercropped with Huacle (Aguilar-Rincón et al, 2010). Loco chilli is cultivated in the Mixteca region, though it is more commonly found in the Sierra Nevada of Puebla (Toledo-Aguilar et al, 2016). Onza is cultivated in the Sierra de Juárez of Oaxaca (Aguilar-Rincón et al, 2010).

Mirador chilli is mostly grown in Veracruz and Hidalgo, while Chocolate chilli is cultivated in the state of Chiapas (Aguilar-Rincón et al, 2010; Ramírez et al, 2010).

Semiwild and wild chillies

Although there are no official records of their conservation area, wild and semiwild chillies represent an important part of the cultural and culinary identity of various Oaxacan regions.

Nanche chilli (semiwild) is native to Oaxaca, found in the Central Valleys. At 120 DAT, plants reach an average height of 145.4cm, with a yield of 11.34g per plant. The fruits are about 1.35cm in length and have a short shelf life, losing 30% of fresh weight within five days (Castellón-Martínez et al, 2014).

Solterito chilli is collected in Central Valley municipalities and shows high variability in growth traits. It grows between 94.6 and 138.8cm tall at 120 DAT, with fruit lengths ranging from 2.88 to 5.7cm (Castellón-Martínez et al, 2014). Other lesser-known types include Paradito or Escuchito, Soltero, de Monte, and Mirasol (with reports of Mirasol collections on the Oaxacan coast) (Pérez-Martínez et al, 2022).

Bolita and Piquín chillies are wild types. The former produces round fruits averaging 1.4cm in length and 1.1cm in diameter, with smooth skin. Piquín refers to various morphotypes also known as Chiltepín, Amashito, Chigolito, among others. At 120 DAT, plants reach 125 to 152.4cm in height, with fruit lengths between 1.07 and 2.26cm and diameters between 0.75 and 0.89cm (Castellón-Martínez et al, 2014). Both types are highly pungent (Aguilar-Rincón et al, 2010).

Guiña Shirundu and Guiña Shuladi are also considered wild types, growing in stubble fields, milpas, backyards, pastures, and abandoned lands in the Isthmus of Tehuantepec, Oaxaca. Guiña Shirundu fruits are round, 0.6 to 1.2cm long, with smooth skin and high pungency. Guiña Shuladi fruits are triangular, 1.8 to 3.0cm long, with smooth skin and moderate pungency. Both are known for their unique flavours in Isthmus cuisine (Aguilar-Rincón et al, 2010; Toledo-Martínez, 2018).

Conservation of chilli diversity in Oaxaca

Currently, chilli diversity is mainly conserved in situ, in the same locations where they have been domesticated, produced and cultivated by backyard or family farmers. As a result, many types are only known locally due to the small-scale cultivation for household use. However, some varieties are at risk of disappearing, including Tusta, Piquín, and Paradito, among others (Castellón-Martínez et al, 2012; Toxqui-Tapia et al, 2022).

Boege (2008) emphasizes that in situ conservation of the genetic diversity of Capsicum annuum in its centre of origin, domestication and diversification facilitates the study of genetic variation in small geographic spaces, due to strong cultural relationships. Recently, strategies such as Community Seed Banks (CSBs) have been implemented for germplasm conservation, undoubtedly including Capsicum spp., although the exact number of safeguarded types is unknown. CSBs emerged from the need to preserve local seeds in situ, directly with the producers themselves. Most were initially implemented to safeguard maize, bean and squash seeds; however, today, some also conserve other species, including chilli peppers, as part of the milpa system. The establishment of CSBs in Mexico was first coordinated by the National Service for the Inspection and Certification of Seeds (SNICS) in 2005, through institutions such as the National Institute for Forestry, Agricultural and Livestock Research (INIFAP), Chapingo Autonomous University (UACH), National Polytechnic Institute (IPN) and National Autonomous University of Mexico (UNAM), among others. In the state of Oaxaca, researchers from the INIFAP were responsible for establishing 11 CSBs in the communities of San Agustín Amatengo, San Jerónimo Coatlán, Santa Catarina Juquila, San Miguel del Puerto, San Pedro Comitancillo, Santa María Jaltianguis, Santiago Yaitepec, Santa María Peñoles, San Andrés Cabecera Nueva, and Putla de Villa Guerrero. The main activities carried out by the CSBs include: the in situ conservation of local crop diversity, seed selection in the field during each cropping cycle, promoting seed exchange among farmers, participation in seed fairs, information transfer through demonstration events and training sessions, and participatory breeding, among others (Aragón-Cuevas, 2016; Vera-Sánchez et al, 2016; SNICS, 2017). On the other hand, the National Technical Assistance Strategy Programme enables trained agricultural technicians to provide guidance and training through farmer field schools to small-scale and backyard producers, aiming to integrate traditional knowledge with scientific and technical expertise to improve productivity and support the conservation of local crops (SADER, 2020).

Over time, small-scale and backyard farmers have made significant efforts to conserve their local chilli crop. This work goes beyond simple preservation – it represents the maintenance of biological and genetic diversity in crops. Such diversity is a key resource for genetic improvement and offers an opportunity to engage primary stakeholders in participatory plant breeding. This approach considers traditional practices and customs related to cultivation, as well as farmers’ preferences for preserving specific varieties based on yield, climate and soil adaptation, and cultural practices. Genetic improvement is important for all types of producers, including smallholders and backyard farmers, as they can benefit from technologies developed through breeding programmes (Castellón-Martínez et al, 2012; Montaño-Lugo et al, 2014). To strengthen the connection with farmers, a participatory plant breeding programme in chilli peppers has been launched in collaboration with vegetable crop researchers at the Campo Experimental Central Valleys of Oaxaca-INIFAP, who have developed technologies whose transfer and adoption still face significant challenges (López-López and Rodríguez-Hernández, 2019; INIFAP, 2023).

Crop breeding is not an easy task – it involves complex challenges, especially given the number of stakeholders involved, including farmers, researchers in the field, government institutions, public policies, and social organizations. Therefore, to ensure that the process is fair and beneficial to all, collaboration among all stakeholders is essential, with traditional farmer knowledge must be valued. For this reason, strong links between producers, researchers and institutions are crucial. Working together, they can contribute to breeding programmes, the creation or strengthening of community seedbanks, seed exchange networks, and other initiatives that promote the conservation of crop diversity, improve production and respect the ancestral knowledge and traditions of local communities.

Most local Oaxaca chilli varieties are preserved ex situ in orthodox seed germplasm banks. These include collections at the Orthodox Seeds from the South collection located at the Campo Experimental Centrall Valleys of Oaxaca (part of Regional Research Center, Pacific South of INIFAP), at the Autonomous University of Chapingo – Southern Regional University Center (UACH-CRUS) in Oaxaca, and accessions at the National Center for Genetic Resources (CNRG) in Jalisco, collected mainly from Chiapas, Guerrero, Veracruz and especially Oaxaca. However, further research programmes are needed to continue exploring, conserving and improving this resource.

In the National Catalogue of Plant Varieties, of the 97 crops listed, only 2% are chilli varieties, most of them commercial germplasm such as Ancho, Guajillo, Jalapeño, Puya, Pimiento, Habanero, and Manzano; only one improved variety of native Oaxacan chilli, chile de Agua, called ‘Nasha,’ is registered (SNICS, 2024). This indicates a clear opportunity to implement genetic improvement programmes as a strategy for use and conservation.

Although all chilli varieties in Oaxaca possess significant agronomic and cultural value, it is evident that some have gained greater visibility and persistence, while others are at risk of disappearing. This situation cannot be explained solely by their agronomic or culinary characteristics, but also by external factors that affect their cultivation and intergenerational transmission. Among these factors are the economic volatility of rural areas, which forces many families to migrate or shift to more profitable crops; agricultural policies that have historically favoured large-scale production and commercial varieties; and the progressive homogenization of diets, influenced by market forces and urban food habits, which reduces the demand for lesser-known local varieties. Additionally, climate change poses an increasing threat, as it alters agricultural cycles and water availability, particularly affecting traditional varieties adapted to specific conditions (Pérez-Martínez et al, 2022; Toxqui-Tapia et al, 2022; Soleri et al, 2023). Therefore, the conservation of chilli diversity in Oaxaca requires not only agronomic and genetic actions, but also a comprehensive approach that takes into account economic, sociocultural and environmental contexts.

Challenges and opportunities for chilli cultivation

Genetic diversity in chilli peppers is protected by maintaining the production of local varieties that possess unique characteristics – such as colour, flavour, resistances or specific culinary uses. Most chilli farmers in Oaxaca currently use traditional open-field methods with agrochemicals and gravity-fed irrigation (Aparicio-del-Moral et al, 2013; López-López et al, 2016). Also small-scale chilli producers in Oaxaca commonly use agrochemicals and gravity-fed irrigation; however, it is important to note that backyard producers generally rely on the rainy season. Pérez-Acevedo et al, (2017) surveyed chile de Agua producers in the Central Valleys during 2013 and 2014, reporting that the majority of the 63 farmers interviewed cultivated half a hectare or less. Regionally, chile de Agua is the most widely grown local variety. Fertilization is carried out either organically or through a combination of organic and inorganic inputs, and pesticides are commonly used. Some of the challenges they face, which sometimes lead to the abandonment of the crop, are:

- Incidence of pests and disease. Diseases include: wilt of chillies (associated with Rhizoctonia, Fusarium, Phytophthora and Pythium), virus diseases and foliage diseases (Altenaria spp. and Cercospora spp., among others). Pests: Fruit weevil, chilli beetle, insect vectors of viruses (López-López and Castro-García 2006; Pérez-Acevedo et al, 2017).

- Untapped productive potential. In chile de Agua, yields range from 3.2t/ha to 7.6t/ha, including fruits considered first, second and third quality due to their size, and in chilli Huacle, yields of 1t/ha in dry weight (Aparicio-del-Moral et al. 2013; López-López and Pérez-Bennetts, 2015; SIAP, 2023).

- High production costs. Mainly due to the use of agrochemicals and fertilizers (Aparicio-del-Moral et al, 2013).

- Inefficient water use, due to the irrigation system used (gravity) (Aparicio-del-Moral et al. 2013; López-López et al, 2016).

- Postharvest losses, including drying of fruit in direct sunlight (increased pathogen damage, fruit staining and loss of compounds) and short shelf life of fresh fruit (moisture loss of at least 15% after 4 d of storage in chilli Tusta, Tabaquero, Piquín and Nanche) (Aparicio-del-Moral et al, 2013; Castellón-Martínez et al, 2014; López-López and Pérez-Bennetts, 2015).

According to previous work carried out on chilli cultivation, potential research opportunities include:

- Rescue and maintain the diversity of chilli morphotypes through breeding programmes such as participatory breeding that involve key stakeholders (farmers) and allow in situ conservation (Sánchez-Hernández et al, 2016; Salgotra and Chauhan, 2023).

- Implement technologies to make water use more efficient, by using a more appropriate irrigation system, such as drip irrigation, which reduces water consumption by up to 50% (SADER, 2024), and using mulch on the soil, which limits evapotranspiration (El-Beltagi et al, 2022).

- Apply organic sources. These improve agronomic characteristics such as yield, plant height, flowering time, among other characteristics such as the nutraceutical quality of the fruits (Márquez-Hernández et al, 2013). For example, the use of compost with application of Azospirillum sp. rhizobacteria in chilli Huacle grown under greenhouse, had similar yields, without statistical differences compared to the control (conventional management) (4,122kg/ha and 4,464kg/ha, respectively) (Galeote-Cid et al, 2022). In addition, the use of organic sources reduces production costs.

- Use production technologies and postharvest management: (1) different planting densities; (2) growing the germplasm under protected conditions – for example, in chile de Agua, if macro-tunnels are used, the yield increases 300-600% more than growing it in open air (Escamirosa-Tinoco et al, 2021); (3) drying in electric or solar dryers, which reduce drying time and prevent contamination by avoiding exposure to open air; in addition, the type of drying allows maintaining or degrading bioactive compounds such as vitamin C and phenolic and carotenoid compounds (Montoya-Ballesteros et al, 2014; Castillo-Téllez et al, 2018); (4) pretreatments in drying, such as blanching (95 °C for 3 min), which can be applied to chillies – as has been done in chile de Agua – to reduce drying time and oxidation of organic compounds (Bautista et al, 2021). If producers are able to reduce post-harvest losses, they will have greater incentives to continue cultivating traditional varieties, which may have lower yields but hold high cultural and gastronomic value.

This is why collaborations among scientists, local farmers, cooks and merchants are essential for the conservation of Oaxaca’s endemic chilli varieties, as each of these actors contributes distinct and complementary knowledge, experiences, and strategies. Involving cooks and merchants helps ensure that chilli peppers continue to be used and sold, which creates demand and prevents their abandonment. For example, if a chilli variety such as chile Huacle or chile de Agua continues to have a valued and profitable culinary use, its cultivation will likely be maintained. The collective work of all stakeholders can contribute to revaluing these chilli varieties as part of Oaxaca’s cultural identity and promote their local consumption. On the other hand, scientists can collaborate with farmers to adapt agricultural practices that protect local varieties from climate change, pests or genetic erosion. Moreover, such collaborations enable the development of educational projects or awareness campaigns highlighting the importance of native chilli varieties.

Conclusions

Mexico is home to a great diversity of chilli peppers, which are a fundamental part of the daily diet of its population. The chilli genetic resources available in Oaxaca are known at the local level but remain largely unknown to the broader population across the various regions of the state, especially outside the areas where they are cultivated. This is primarily because most of these varieties are native, semi-domesticated or wild. Oaxaca is the state with the greatest diversity, represented by at least 25 types distributed across agroecological niches where they are still preserved. Therefore, it is essential to continue efforts in their conservation and sustainable use.

The importance of conserving genetic resources lies in ensuring access to genetic material that can be used in research, enabling deeper understanding and scientific advancement. At the same time, it can be incorporated into breeding programmes to help develop alternatives to address current challenges faced by chilli cultivation – whether biotic or abiotic factors – many of which stem from vulnerabilities caused by climate change. This enables agriculture to adapt to changing conditions and contributes to food security. The conservation of chilli pepper diversity in Oaxaca largely depends on the work of small-scale producers, who, through their traditional agricultural practices and local knowledge, have managed to maintain a wide variety of chilli types over time. This conservation is not solely genetic or agronomic; it is deeply interwoven with the culinary and cultural traditions of the state’s diverse regions. In many Oaxacan communities, the cultivation, use and selection of specific chilli varieties are tied to food practices passed down through generations, where each type of chilli is used according to its flavour, pungency, colour, texture or symbolic value. Therefore, the conservation of chilli diversity in Oaxaca cannot be understood without recognizing the central role of local producers as custodians of biocultural knowledge.

Acknowledgments

We also acknowledge the support provided by the researchers Luis Eduardo García Mayoral, Miguel Ángel Cano García, Filemón Rafael Rodríguez Hernández, Salvador Montes Hernández and Leodegario Osorio Alcalá, whose help allowed us to complete the description of the environment in this work.

Author contributions

Yeimy Clemencia Ramírez-Rodas prepared the study proposal, collected and organized the data and information, and wrote the manuscript. Luis Yobani Gayosso-Rosales contributed to the review and improvement of the study proposal, data collection, writing, editing and improving drafts of the manuscript. Ulises Santiago-López contributed to the review and improvement of the study proposal, editing and improving drafts of the manuscript.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

Aguilar-Meléndez, A., Lira Noriega, A. (2018). ¿Dónde crecen los chiles en México?. En: Los chiles que le dan sabor al mundo. Eds. A. Aguilar-Meléndez, M. A. Vásquez-Dávila, E. Katz y M. R. Hernández Colorado editores (Universidad Veracruzana, México y IRD, Francia) 75–92.

Aguilar-Rincón V H, T Corona-Torres, P López-López, L LatournerieMoreno, M. Ramírez-Meraz, H Villalón-Mendoza, J A AguilarCastillo. (2010). Los Chiles de México y su distribución (SINAREFI, Colegio de Postgraduados, INIFAP, IT-Conkal, UNAL y UAN. Estado de México, México), 108 p.

Ambrosio S., F. (2007). Análisis de los aspectos socio-culturales y económicos del agroecosistema chile de agua (Capsicum annuum L.) en Cuilapam de Guerrero, Oaxaca. Tesis de Maestría, Instituto Tecnológico del Valle de Oaxaca, México.

Aparicio-del-Moral, J. O., Tornero-Campante, M. A., Sandoval-Castro, E., Villarreal-Manzo, L. A., de los Ángeles Rodríguez-Mendoza, M. (2013). Factores sociales y económicos del cultivo de chile de agua (Capsicum annum L.) en tres municipios de los valles centrales de Oaxaca. Ra Ximhai 9(1), 17–24.

Aragón C., F. (2016). México: Bancos comunitarios de semillas en Oaxaca. En: Bancos Comunitarios de Semillas: Orígenes, Evolución y Perspectivas, eds: Vernooy R., P Shrestha., B Sthapit,. Y M Ramírez., (Bioversity International, Lima Perú), 136–139.

Báez-Vera, P. J., Malda Barrera, G., Zocchi, D. M. (2018). El Arca del Gusto en México: Productos, saberes e historias del patrimonio gastronómico (Slow Food Editore, Bra., Italy), 181p .

Bautista, P. B., Juárez, N. A., Hernández, I. H. (2021). Efecto del escalde en el secado de chile de agua producido en la región de los valles centrales de Oaxaca. Universidad & ciencia 10, 50–64.

Boege, S.E. (2008). El patrimonio biocultural de los pueblos indígenas de México ( Instituto Nacional de Antropología e Historia y Comisión Nacional para el Desarrollo de los Pueblos Indígenas, Ciudad de México, México), 344 p.

Castellón-Martínez E., Chávez-Servia, J. L., Carrillo-Rodríguez, J. C., Vera-Guzman, A. M. (2012). Preferencias de consumo de chiles (Capsicum annuum L.) nativos en los Valles Centrales de Oaxaca, México. Revista Fitotecnia Mexicana 35 (5), 27–35.

Castellón-Martínez, E., Carrillo-Rodríguez, J. C., Chavez-Servia, J. L., Vera-Guzmán, A. M. (2014). Variación fenotípica de morfotipos de chile (Capsicum annuum L.) nativo de Oaxaca, México. Phyton 83(2), 225–236.

Castillo-Téllez, M. C., Figueroa, I. P., Téllez, B. C., Vidaña, E. C. L., Ortiz, A. L. (2018). Solar drying of Stevia (Rebaudiana Bertoni) leaves using direct and indirect technologies. Solar Energy, 159, 898–907. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.solener.2017.11.031

El-Beltagi, H. S., Basit, A., Mohamed, H. I., Ali, I., Ullah, S., Kamel, E. A., Shalaby, T. A., Ramada, K. M. A., Alkhateeb A. A., Ghazzawy, H. S. (2022). Mulching as a sustainable water and soil saving practice in agriculture: A review. Agronomy 12(8):1881. doi: https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy12081881.

Escamirosa-Tinoco, C., Martínez-Gutiérrez, G. A., Morales, I., Aquino-Bolaños, T., Cortés-Martínez, C. I., Cruz-Andrés, O. R. (2021). Rendimiento de chile de agua bajo diferentes cubiertas de macrotúnel. Revista fitotecnia mexicana 44(3), 333–340.

FAO (2012). Segundo plan de acción mundial para los recursos fitogenéticos para la alimentación y la agricultura. FAO-Comisión de Recursos Genéticos para la Alimentación y la Agricultura. 24 p. Url: https://www.fao.org/4/i2650s/i2650s.pdf.

Galeote-Cid, G., Cano-Ríos, P., Ramírez-Ibarra, J. A., Nava-Camberos, U., Reyes-Carrillo, J. L., Cervantes-Vázquez, M. G. (2022). Comportamiento del chile Huacle (Capsicum annuum L.) con aplicación de compost y Azospirillum sp. en invernadero. Terra Latinoamericana 40:1–12 e828. doi: https://doi.org/10.28940/terra.v40i0.828.

Guzmán-Mendoza, R., Hernández-Hernández, V., Salas-Araiza, M. D., Núñez-Palenius, H. G. (2022). Diversidad de especies de plantas arvenses en tres monocultivos del Bajío, México. Polibotánica, (53), 69–85.

INIFAP (2023). Instituto Nacional de Investigaciones Forestales Agrícolas y Pecuarias. Tecnología para la producción de chile de agua en ambiente protegido. Url: https://www.gob.mx/inifap/articulos/tecnologia-para-la-produccion-de-chile-de-agua-en-ambiente-protegido?idiom=es

López-López, P., Castro-García, F. H. (2006). La diversidad de los chiles (Capsicum spp., Solanaceae) de Oaxaca. En: Avances de investigación de la red de hortalizas del SINAREFI , eds. López L. P y S. Montes H. (Instituto Nacional de Investigaciones Forestales, Agrícolas y Pecuarias, Campo Experimental Bajío. Celaya, Gto. México), 135–178.

López-López, P., Pérez-Bennetts, D. (2015). El chile huacle (Capsicum annuum sp.) en el estado de Oaxaca, México. Agroproductividad 8(1), 37–39.

López-López, P., Rodríguez-Hernández, R. (2019). Evaluación de chile de agua (Capsicum annuum L.) en ambiente protegido y poda en los valles centrales de Oaxaca. Producción Agropecuaria: Un enfoque integrado 47– 52.

López-López, P., Rodríguez-Hernández, R., Bravo-Mosqueda, E. (2016). Impacto económico del chile huacle (Capsicum annuum L) en el estado de Oaxaca. Revista Mexicana de Agronegocios 38, 317–327.

Márquez-Hernández, C., Cano-Ríos, P., Figueroa-Viramontes, U., Avila-Diaz, J. A., Rodríguez-Dimas, N., García-Hernández, J. L. (2013). Rendimiento y calidad de tomate con fuentes orgánicas de fertilización en invernadero. Phyton 82(1), 55–61.

Martínez-Martínez, R., Méndez-Infante, I., Castañeda-Aldaz, H. M., Vera-Guzmán, A. M., Chávez-Servia, J. L., Carrillo-Rodríguez, J. C. (2014). Heterosis interpoblacional en agromorfología y capsaicinoides de chiles nativos de Oaxaca. Revista Fitotecnia Mexicana 37(3), 199–207.

Montaño-Lugo, M. L., Velasco Velasco, V. A., Ruíz Luna, J., Campos Ángeles, G. V., Rodríguez Ortiz, G., Martínez Martínez, L. (2014). Contribución al conocimiento etnobotánico del chile de agua (Capsicum annuum L.) en los Valles Centrales de Oaxaca, México. Revista mexicana de ciencias agrícolas, 5(3), 503–511.

Montoya-Ballesteros, L. C., González-León, A., García-Alvarado, M. A., Rodríguez-Jimenes, G. C. (2014). Bioactive compounds during drying of chili peppers. Drying Technology 32(12), 1486–1499. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/07373937.2014.902381.

Ovando, CME. (2007). Producción de chile costeño con agribón y fertirriego en la costa de Oaxaca. Revista Agroproduce, 20–21.

Pérez-Acevedo, C. E., Carrillo-Rodríguez, J. C., Chávez-Servia, J. L., Perales-Segovia, C., Enríquez del Valle, R., Villegas-Aparicio, Y. (2017). Diagnóstico de síntomas y patógenos asociados con marchitez del chile en Valles Centrales de Oaxaca. Revista mexicana de ciencias agrícolas 8(2), 281–293. doi: https://doi.org/10.29312/remexca.v8i2.50.

Pérez-Martínez, A. L., Eguiarte, L. E., Mercer, K. L., Martínez-Ainsworth, N. E., McHale, L., van der Knaap, E., Jardón-Barbolla, L. (2022). Genetic diversity, gene flow, and differentiation among wild, semiwild, and landrace chile pepper (Capsicum annuum) populations in Oaxaca, Mexico. American Journal of Botany 109(7), 1157–1176. doi: https://doi.org/10.1002/ajb2.16019.

Pickersgill, B. 2016. Chile Peppers (Capsicum spp.). En: Ethnobotany of Mexico. Interactions, eds. Lira, R., Casas, A., Blancas, J., (Springer Science + Business Media, New York, NY), 417–437.

Ramírez, H., Amado-Ramírez, C., Benavides-Mendoza, A., Robledo-Torres, V., Martínez-Osorio, A. (2010). Prohexadiona-Ca, AG3, ANOXA y BA modifican indicadores fisiológicos y bioquímicos en chile Mirador. Revista Chapingo. Serie horticultura 16(2), 83–89.

Rodríguez-Campos, E. (2018). La diversidad genética de Capsicum annum de México. En: Los chiles que le dan sabor al mundo, eds. A. Aguilar-Meléndez, M. A. Vásquez-Dávila, E. Katz y M. R. Hernández Colorado editores, (Universidad Veracruzana, México y IRD Éditions, Francia), 52–67.

Ruiz-Núñez, N. d. C.; Vásquez-Dávila, M.A. Etnoecología del chile de campo en Guelavía, Oaxaca. 2018. En: Los chiles que le dan sabor al mund, eds. A. Aguilar-Meléndez, M. A. Vásquez-Dávila, E. Katz y M. R. Hernández Colorado editores, (Universidad Veracruzana, México y IRD Éditions, Francia), 260–280.

SADER (2020). Secretaría de Agricultura y Desarrollo Rural. Estrategia de Acompañamiento Técnico. Url: https://www.gob.mx/agricultura/articulos/estrategia-de-acompanamiento-tecnico.

SADER (2024). Secretaría de Agricultura y Desarrollo Rural. Maximizando la eficiencia agrícola: Sistema de riego por goteo. Url: https://www.gob.mx/agricultura/articulos/maximizando-la-eficiencia-agricola-sistema-de-riego-por-goteo

Salgotra, R. K., Chauhan, B. S. (2023). Genetic diversity, conservation, and utilization of plant genetic resources. Genes, 14(1), 174. doi: https://doi.org/10.3390/genes14010174.

Sánchez-Hernández, C., Sánchez-Hernández, M. A., González-Montiel, L., Vicente-Pinacho, A. J. (2016). Mejoramiento participativo del chile huacle en Cuicatlán, Oaxaca, México. En: Conocimiento multidisciplinario. Hablando de emprendurismo educación y derecho, ed. B. López Azamar, (Universidad del Papaloapan. Oaxaca, México), 135–149.

Sanjuan Martínez, J. Características vegetativas y de frutos de tres tipos de chiles de oaxaca producidos en invernadero. (2020). Contribución al Conocimiento Científico y Tecnológico en Oaxaca 4(4), 50–59.

SanJuan Martinez, J., Ortiz Hernández, Y. D., Aquino Bolaños, T., Cruz Izquierdo, S., Pérez Pacheco, R. Evaluación ex situ de seis chiles nativos de Oaxaca en invernadero. (2022). Revista de Ciencias Agronómicas Aplicadas y Biotecnología 2, 101–107.

Santiago-Luna, E. G., Carrillo-Rodríguez, J. C., Chávez-Servia, J. L., del Valle, R. E., Villegas-Aparicio, Y. (2016). Phenotypic variation in tusta pepper populations. Agronomía Mesoamericana 27, 139–149. doi: https://doi.org/10.15517/am.v27i1.21893.

Sclavo-Castillo, D., Volkow, L. P., Martínez, E. H. (2024). El chile tabiche: memoria, reencuentro y acción comunitaria en Santo Domingo Tomaltepec, Oaxaca, México. Naturaleza y Sociedad. Desafíos Medioambientales 8, 79–103. doi: https://doi.org/10.53010/NLTT9430.

SIAP (2023). Anuario Estadístico de la Producción Agrícola. Url: https://www.gob.mx/siap/acciones-y-programas/produccion-agricola-33119

Slow Food (2025). Url: https://www.fondazioneslowfood.com/en/ark-of-taste-slow-food/chilhuacle/

SNICS (2017). Bancos Comunitarios de Semillas como estrategia de Conservación in situ. url: https://www.gob.mx/snics/acciones-y-programas/bancos-comunitarios-de-semillas-como-estrategia-de-conservacion-in-situ

SNICS (2024). Catálogo Nacional de Variedades Vegetales. Url: https://www.gob.mx/snics/es/articulos/catalogo-nacional-de-variedades-vegetales-en-linea

Soleri, D., Cleveland, D. A., Aragón Cuevas, F., Jimenez, V., Wang, M. C. (2023). Traditional foods, globalization, migration, and public and planetary health: the case of tejate, a maize and cacao beverage in Oaxacalifornia. Challenges, 14(1), 9.

Taitano, N., Bernau, V., Jardón-Barbolla, L., Leckie, B., Mazourek, M., Mercer, K., McHale, L., Michel, A., Baumler, D., Kantar, M., van der Knaap, E. (2019). Genome-wide genotyping of a novel Mexican chile pepper collection illuminates the history of landrace differentiation after Capsicum annuum L. domestication. Evolutionary Applications 12, 78–92. doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/eva.12651.

Toledo-Aguilar, R., López-Sánchez, H., López, P. A., Guerrero-Rodríguez, J. D. D., Santacruz-Varela, A., Huerta-de la Peña, A. (2016). Diversidad morfológica de poblaciones nativas de chile poblano. Revista mexicana de ciencias agrícolas 7(5), 1005–1015.

Toledo-Martínez, A. El shigundu, uno de los sabores de la cocina istmeña. (2018). En: Los chiles que le dan sabor al mundo, eds. A. Aguilar-Meléndez, M. A. Vásquez-Dávila, E. Katz y M. R. Hernández Colorado editores, (Universidad Veracruzana, México y IRD Éditions, Francia), 68–74.

Toxqui-Tapia, R., Peñaloza-Ramírez, J. M., Pacheco-Olvera, A., Albarran-Lara, L., Oyama, K. (2022). Genetic diversity and genetic structure of Capsicum annuum L., from wild, backyard and cultivated populations in a heterogeneous environment in Oaxaca, Mexico. Polibotánica 53, 87–103. doi: https://doi.org/10.18387/polibotanica.53.6.

UNAM (2007). Capsicum rhomboideum (Dunal) Kuntze. Herbario Nacional de México (MEXU), Plantas Vasculares. Departamento de Botánica, Instituto de Biología de la Universidad Autónoma de México. url: https://datosabiertos.unam.mx/IBUNAM:MEXU:1242472.

UNESCO (2010). La cocina tradicional mexicana: Una cultura comunitaria, ancestral y viva y el paradigma de Michoacán. Url: https://ich.unesco.org/es/RL/la-cocina-tradicional-mexicana-una-cultura-comunitaria-ancestral-y-viva-y-el-paradigma-de-michoacn-004009

Vera-Guzmán, A. M., Chávez-Servia, J. L., Carrillo-Rodríguez, J. C., López, M. G. (2011). Phytochemical evaluation of wild and cultivated pepper (Capsicum annuum L. and C. pubescens Ruiz & Pav.) from Oaxaca, Mexico. Chilean journal of agricultural research 71(4), 578.

Vera-Sánchez, K. S, R. González S, F. Aragón C. (2016). Bancos comunitarios de semillas en México: Una estrategia de conservación in situ. En: Bancos Comunitarios de Semillas: Orígenes, Evolución y Perspectivas, eds. Vernooy R., P Shrestha., B Sthapit,. Y M Ramírez, (Bioversity International, Lima Perú), 248–253.

Virgen J., S. D. (2006). Rentabilidad y mercadeo de la producción de chile de agua bajo invernadero en el municipio de Ayoquezco de Aldama, Oaxaca. Tesis de Licenciatura, Departamento de Fitotecnia.Universidad Autónoma Chapingo.Texcoco, México.