Seed germinability of Stylosanthes spp. (Fabaceae) accessions under water stress conditions

Vitor Oliveira dos Santos*, Aritana Alves da Silva, Robson de Jesus Santos, Uasley Caldas de Oliveira, Marilza Neves do Nascimento, Claudineia Regina Pelacani

Universidade Estadual de Feira de Santana, Feira de Santana, Bahia, Brazil

* Corresponding author: Vitor Oliveira dos Santos (vitor.agro.uefs@gmail.com)

Abstract: This study aimed to evaluate and compare the germinative performance of seeds from accessions of Stylosanthes spp. held in the Forage Germplasm Bank of the State University of Feira de Santana (BGF-UEFS), Brazil, under water stress conditions during the initial phases of germination. Germination tests were conducted using seeds from six accessions subjected to different osmotic potentials (0.0MPa – distilled water, -0.2, -0.4, -0.6 and -0.8MPa) prepared with polyethylene glycol 6000 (PEG 6000). The experimental design was completely randomized, using 25 seeds per replicate for each treatment. The seeds were evaluated over a period of 5 days under water stress conditions, followed by an additional 5-day recovery period in distilled water for the seeds remaining from the -0.8MPa treatments. The following variables were measured: germination percentage (G%), mean germination time (MGT), germination speed index (GSI), and germination recovery (GR). The results indicated an interaction between factors affecting the germinative behaviour of the Stylosanthes spp. accessions for all variables. The genotypes showed significant reductions in G%, with accessions BGF 12-014, BGF 10-018 and BGF 10-029 exhibiting the best performance under the most severe osmotic potential (-0.8MPa). MGT and GSI were also significantly affected by increased water stress. Accessions BGF 12-014, BGF 10-018 and BGF 10-029 were the most promising based on their germinative performance under water stress conditions simulated with PEG 6000 during the early germination phase.

Keywords: Forage legume, polyethylene glycol 6000, osmotic potential, germination, water deficit.

Introduction

The Brazilian Semi-Arid region (SAB) comprises 1,262 municipalities, most of which are located in the northeastern part of the country (IBGE, 2023). This territory is notably characterized by a hot, dry climate and highly irregular rainfall throughout the year, which directly impacts the region’s socioeconomic development (Simões et al, 2022), as water scarcity significantly influences local agricultural and livestock activity.

With regard to livestock farming in the SAB, the region is home to approximately 65% and 90% of the country’s sheep and goat herds, respectively, and about 14.8% of the national cattle herds (IBGE, 2018). Most of this livestock production is carried out under extensive systems that rely on low-yielding forages, especially during periods of reduced rainfall (Souza et al, 2020). Moreover, the climatic conditions of the SAB limit water availability for the development of forage species, and animal feeding is often partially compromised (Gusha et al, 2015). During the driest periods, producers are forced to seek alternative feed sources because pasture forage production becomes insufficient to meet the animals’ nutritional requirements, resulting in increased costs.

In addition, few studies focused on improving forage plants adapted to the SAB have been conducted to date. Consequently, the search for alternatives to reduce livestock production costs in the region remains limited to a few studies. In light of these challenges, it is essential to explore plant genetic resources that are tolerant to the climatic conditions of the SAB to mitigate the impacts of irregular rainfall in the region. Among the forage species that demonstrate tolerance to water stress are elephant grass (Cenchrus purpureus (Schumach.) Morrone.), lead tree (Leucaena leucocephala (Lam.) de Wit), mexican lilac (Gliricidia sepium Jacq.), birdwood grass (Cenchrus ciliaris L.), and species of the genus Stylosanthes Sw.

The genus Stylosanthes Sw. (Fabaceae Lindl.) is widely distributed across the Americas, with Brazil harbouring the greatest diversity of species – 38 in total, 17 of which are endemic to the country (Flora e Funga do Brasil, 2020). Additionally, several species within the genus are considered plant genetic resources because of their suitability for animal feed (Canzi et al, 2021) owing to their high forage potential, biomass production and protein content. Furthermore, their adaptation to acidic soils and tolerance to water scarcity (Gonzalez et al, 2000; Liu et al, 2019; Habermann et al, 2021) make them particularly suitable for cultivation in regions with edaphoclimatic conditions, such as the SAB.

Notably, the semi-arid region is considered one of the centres of diversity for the Stylosanthes genus, as evidenced by expeditions carried out in the semi-arid mesoregions of Bahia between 2007 and 2019 (Santos Júnior et al, 2022). Genotypes collected during these expeditions are conserved in the Forage Germplasm Bank of the State University of Feira de Santana (BGF-UEFS), located in the municipality of Feira de Santana, Bahia, with approximately 370 accessions catalogued from these regions (Santos Júnior et al, 2022; Silva et al, 2024). However, these materials still lack comprehensive studies on their genotypic, morphoagronomic and physiological traits, as well as their performance under different environmental conditions, especially under water stress, which is one of the main abiotic factors limiting productivity.

Water stress affects numerous physiological processes in plants, including the reduction in transpiration rates and degradation of photosynthetic pigments, ultimately impacting photosynthetic efficiency (Lawlor and Cornic, 2002; Hussain et al, 2018). Nevertheless, Hussain et al (2018) highlighted that those plants in water-limited environments exhibit a range of adaptive responses that confer tolerance to water stress.

During germination, the seed rehydrates its tissues through water absorption, triggering the embryo's metabolic processes and resuming its growth (Bradford, 1990; Bewley and Black, 1994). In this context, water availability directly influences the success of this process, as germination may be inhibited or delayed under water deficits (Bradford, 1990; Roberts, 1973; Bewley and Black, 1994). Consequently, when seeds are exposed to such environmental conditions in productive areas, germination may be interrupted or postponed, leading to field emergence irregularities, inefficient land use, and reduced forage production, negatively impacting the feed supply for livestock.

Thus, assessing seed germinability under water deficit or limiting moisture conditions provides valuable insights for identifying genotypes tolerant to semi-arid regions. This is especially relevant because germination is one of the most critical stages in the plant life cycle. Polyethylene glycol 6000 (PEG 6000) has been widely used to simulate water restriction during seed germination (Braccini et al, 1996), as its high molecular weight prevents it from penetrating the plant cell membrane, thereby avoiding toxicity (Marcos Filho, 2002).

In this context, understanding the germinative behaviour of genotypes subjected to water-limited conditions is essential for selecting materials suitable for cultivation in arid environments. Therefore, this study aimed to evaluate and compare the germinability of seeds from Stylosanthes spp. accessions held in BGF-UEFS under water stress during germination.

Materials and methods

The experiment was conducted in the Seed Germination Laboratory (LAGER) at the State University of Feira de Santana (UEFS), Brazil. The genetic materials used in this study were conserved in the Forage Germplasm Bank of UEFS (BGF-UEFS) and were obtained from accessions propagated between 2014 and 2020, with progenitors collected from the semi-arid region of Bahia (Table 1) and stored following the methodology of Gómez-Campo (2006), kept in properly labelled kraft paper envelopes, sealed with galvanized staples, and placed in airtight containers with silica gel as a moisture indicator, at room temperature (approximately 25.1ºC); with seed moisture content ranging approximately between 4.5% and 8%. Moreover, the accessions were selected based on seed viability above 80%.

Table 1. Passport data of Stylosanthes spp. accessions stored in the Forage Germplasm Bank of the State University of Feira de Santana (BGF-UEFS)

|

Accession |

Species |

Year of seed regeneration |

Municipality |

Coordinates |

|

BGF 10-016 |

S. scabra |

2020 |

Queimadas |

10°54’40”S/39°12’17”W |

|

BGF 12-014 |

S. humilis |

2020 |

Canarana |

11º48’597”S/41º42’066”W |

|

BGF 014-P137-2 |

S. scabra |

2020 |

Seabra |

12º27’311”S/42º11’452”W |

|

BGF 10-018 |

S. scabra |

2014 |

Candeal |

11°49’49,8”S/ 39°07’08,5”W |

|

BGF 10-034 |

S. scabra |

2014 |

Feira de Santana |

12°09’719”S/38°57’696”W |

|

BGF 10-029 |

S. viscosa |

2014 |

Canudos |

09°54’29,9”S/39°03’17,2”W |

To overcome seed coat dormancy, mechanical scarification was performed using sandpaper (sandpaper no. 150) (Silva et al, 2024). Additionally, to reduce contamination during the experiment, the seeds were disinfected in a 0.5% sodium hypochlorite solution for 10 min and then rinsed with distilled water.

Seeds from the accessions were subjected to treatment with PEG 6000 solutions at different osmotic potentials (0.0MPa for pure distilled water, -0.2MPa, -0.4MPa, -0.6MPa and -0.8MPa), simulating water stress, as proposed by Villela et al (1991), with adjustments made at a temperature of 30°C. Germination tests were carried out in 60mm glass Petri dishes lined with two sheets of sterilized germination paper (germitest type) moistened with 2ml of the respective pre-prepared PEG 6000 solutions. Every two days, the Petri dishes and germination papers were replaced, and the osmotic solutions were replenished to maintain the target osmotic potentials for each treatment.

The tests were conducted in biochemical oxygen demand (B.O.D.) germination chambers, under constant temperature (30°C) and in the dark. Germination was defined as the emergence of the radicle (≥ 2mm), with daily counts recorded throughout the 5-day evaluation period. The choice of 5 days was based on preliminary tests (unpublished data), which showed that after this period, the germination of the remaining seeds was not significant.

On the fifth day of evaluation, seeds that did not show radicle protrusion in -0,8MPa were removed from the PEG solution, rinsed to eliminate residual PEG 6000, and transferred to new Petri dishes with fresh germitest paper moistened with 2ml of distilled water. This set of remaining seeds was returned to the B.O.D. chamber for an additional 5-day period, referred to as the ‘germination recovery’ phase. Germination during this phase was recorded, and the results were expressed as the percentage of recovered seeds, based on a total of 25 sown seeds per replicate.

The germination percentage (G%) was calculated according to Laboriau and Valadares (1976): G% = (N/A) × 100, where: G% = germination percentage, N = total number of germinated seeds, A = total number of seeds tested. Mean germination time (MGT; days) was calculated following Labouriau (1993): MGT = (Σni·ti)/Σni, where: ni = number of seeds germinated at time interval ti in days. Germination speed index (GSI; seeds·day⁻¹) was calculated according to Maguire (1962): GSI = G1/N1 + G2/N2 + ... + Gn/Nn, where: G1, G2, ..., Gn = number of seeds germinated on each respective day, N1, N2, ..., Nn = number of days from the start of the test to each respective counting day.

The experiment followed a completely randomized design with four replicates, each consisting of one Petri dish containing 25 seeds. The data were tested for the assumptions of residual normality using the Shapiro–Wilk test and for homogeneity of variances using Bartlett’s test. For G%, because the assumptions required for analysis of variance (ANOVA) were not initially met, the data were transformed using the arcsine square root function: arcsin√(x/100).

Once the assumptions were satisfied, ANOVA was conducted. Upon observing a significant interaction between the factors (P-value < 0.05), regression curves were constructed using the best-fit model (based on R² values). To compare accession performance within each osmotic potential, the means were grouped using the Scott–Knott test (Scott & Knott, 1974).

All analyses and plots were conducted using R statistical software (version 2024.12.0+467) (R Core Team, 2024).

Results

The analysis of variance (Table 2) revealed a significant interaction between accessions and osmotic potentials for all variables analyzed: germination (G%), germination speed index (GSI) and mean germination time (MGT) indicating that the combination of osmotic potentials and genotypes had a differential effect on seed germination behaviour.

Table 2. Summary of the analysis of variance (ANOVA) for the variables evaluated during germination of six accessions of the genus Stylosanthes spp. subjected to different water potentials of PEG 6000. DF, degrees of freedom; G%, germination; GSI, germination speed index; MGT, mean germination time; CV, coefficient of variation; **, significant (p-value < 0.01) and *, (p-value < 0.05) by the F-test, respectively.

|

Variation source |

DF |

G% |

GSI |

MGT |

|

Accession |

5 |

12.41** |

17.13* |

4.62** |

|

Osmotic potential |

4 |

80.24** |

499.60** |

85.32** |

|

Accession X osmotic potential |

20 |

4.38** |

6.23** |

5.07** |

|

Residual |

90 |

|||

|

CV(%) |

13.19 |

12.19 |

21.58 |

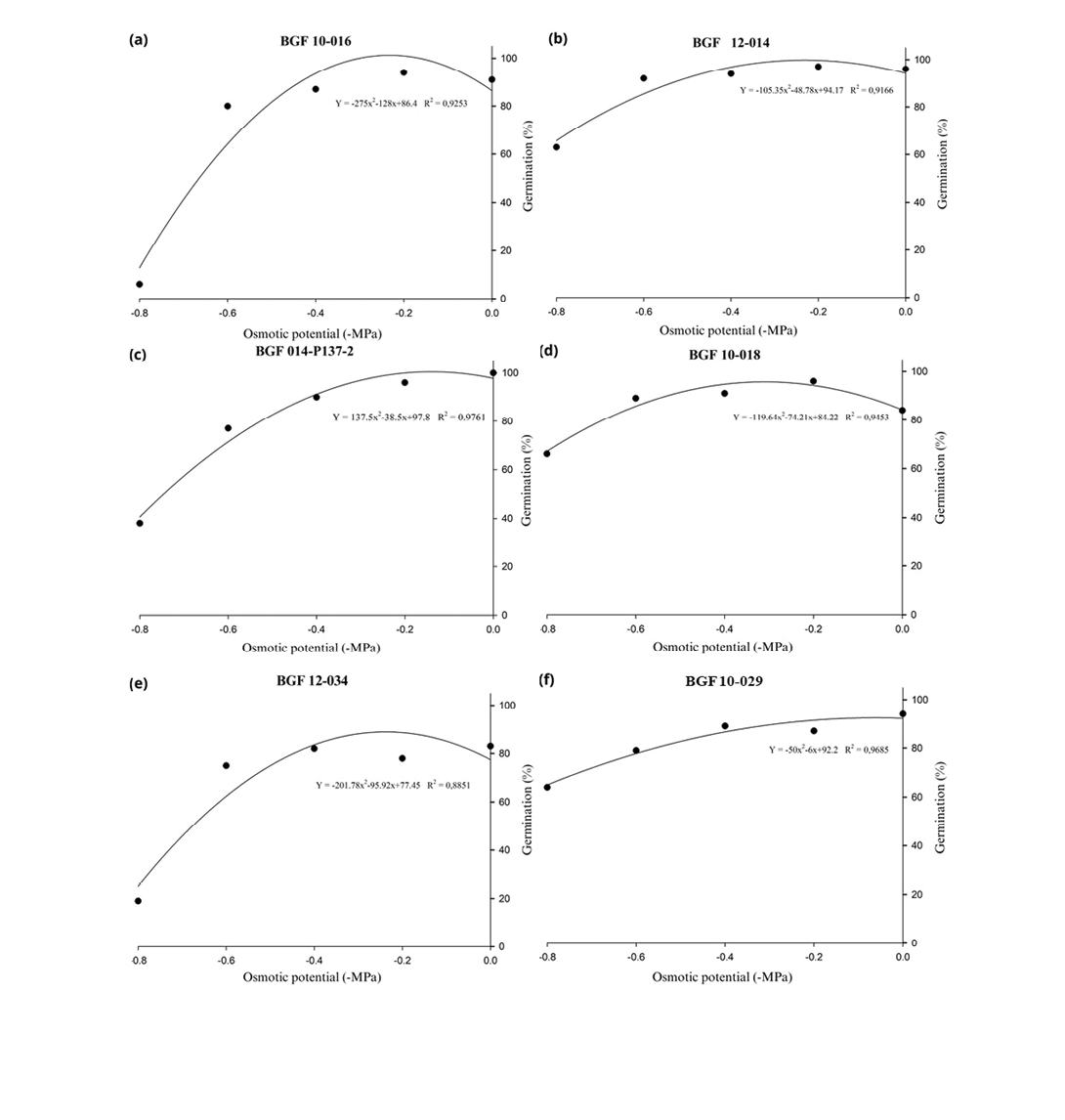

Figure 1 shows the influence of osmotic potential on the germination of seeds from different Stylosanthes spp. accessions based on regression analysis. Differences among accessions were evident, as indicated by the distinct slopes and intercepts of the regression curves. Additionally, the R² values associated with each regression model indicated a good fit, ranging from 88.51% to 97.61%, demonstrating a strong correlation between osmotic potential and germination under the tested conditions. At osmotic potentials of 0.0, -0.2 and -0.4MPa, the accessions exhibited similar performance, with little variation in the germination percentage. However, at lower osmotic potentials (-0.6 and -0.8MPa), more pronounced differences in the performance of the tested genetic materials were observed than at higher potentials, highlighting that the genotypes exhibit divergent performances, especially under more severe water stress conditions.

Accessions BGF 10-029 (Figure 1f), BGF 12-014 (Figure 1b), and BGF 10-018 (Figure 1d) exhibited less steep regression curves than the other materials, indicating lower sensitivity to water stress. Moreover, under the most negative osmotic potential, these accessions maintained relatively high mean germination percentages, ranging from 63% to 66%. In contrast, accession BGF 014-P137-2 (Figure 1c) showed intermediate performance under the same conditions, with a germination rate of 38%. Accessions BGF 10-034 (Figure 1e) and BGF 10-016 (Figure 1a) showed the poorest performance under the imposed water stress conditions, with germination percentages at the most negative osmotic potential reaching only 19% and 6%, respectively, reflecting substantial reductions compared to the control treatment (0.0MPa), and indicating that under low water availability, these genetic materials are notably disadvantaged in terms of germination occurrence.

Figure 1. Regression plots showing the effect of different concentrations of PEG 6000 on the osmotic potential and seed germination of Stylosanthes spp. accessions. PEG 6000 concentrations were used to simulate water stress, ranging from 0.0 to -0.8MPa. Each point represents the mean of four replications, and the lines represent the fit of the data using a quadratic regression model.

The breakdown of accession performance at each osmotic potential is presented in Table 3. According to the Scott–Knott clustering test, under control conditions, the materials were divided into two groups, with accessions BGF 10-016, BGF 12-014, BGF 014-P137-2 and BGF 10-029 exhibiting higher germination rates. Additionally, at -0.2MPa, all accessions were grouped together, except for BGF 10-036, whose mean value was significantly lower than that of the other genotypes. At osmotic potentials of -0.4 and -0.6MPa, no significant differences were detected among the accessions, as a single group was formed based on the genotype.

Furthermore, at the most negative osmotic potential, germination percentages among accessions once again showed significant differences, as this level of the factor yielded the greatest variation in the results. The accessions that demonstrated the best performance under these conditions were BGF 12-014, BGF 10-018 and BGF 10-029, with germination percentages of 63.0%, 66.0% and 64.0%, respectively. At the same osmotic potential, all other accessions were considered statistically different from the aforementioned group and from each other, as BGF 014-P137-2, BGF 10-034 and BGF 10-016 were each assigned to separate groups.

Table 3. Germinability of seeds from Stylosanthes spp. accessions subjected to different concentrations of PEG 6000. Means followed by the same letter in the columns do not differ from each other according to the Scott–Knott test at 5%.

|

Germination percentage (G%) |

|||||

|

Osmotic Potential (-MPa) |

|||||

|

Accession |

0.0 |

-0.2 |

-0.4 |

-0.6 |

-0.8 |

|

BGF 10-016 |

91.0 a |

94.0 a |

87.0 a |

80.0 a |

6.0 d |

|

BGF 12-014 |

96.0 a |

97.0 a |

94.0 a |

92.0 a |

63.0 a |

|

BGF 014-P137-2 |

100.0 a |

96.0 a |

90.0 a |

77.0 a |

38.0 b |

|

BGF 10-018 |

84.0 b |

96.0 a |

91.0 a |

89.0 a |

66.0 a |

|

BGF 10-034 |

83.0 b |

78.0 b |

82.0 a |

75.0 a |

19.0 c |

|

BGF 10-029 |

94.0 a |

87.0 a |

89.0 a |

79.0 a |

64.0 a |

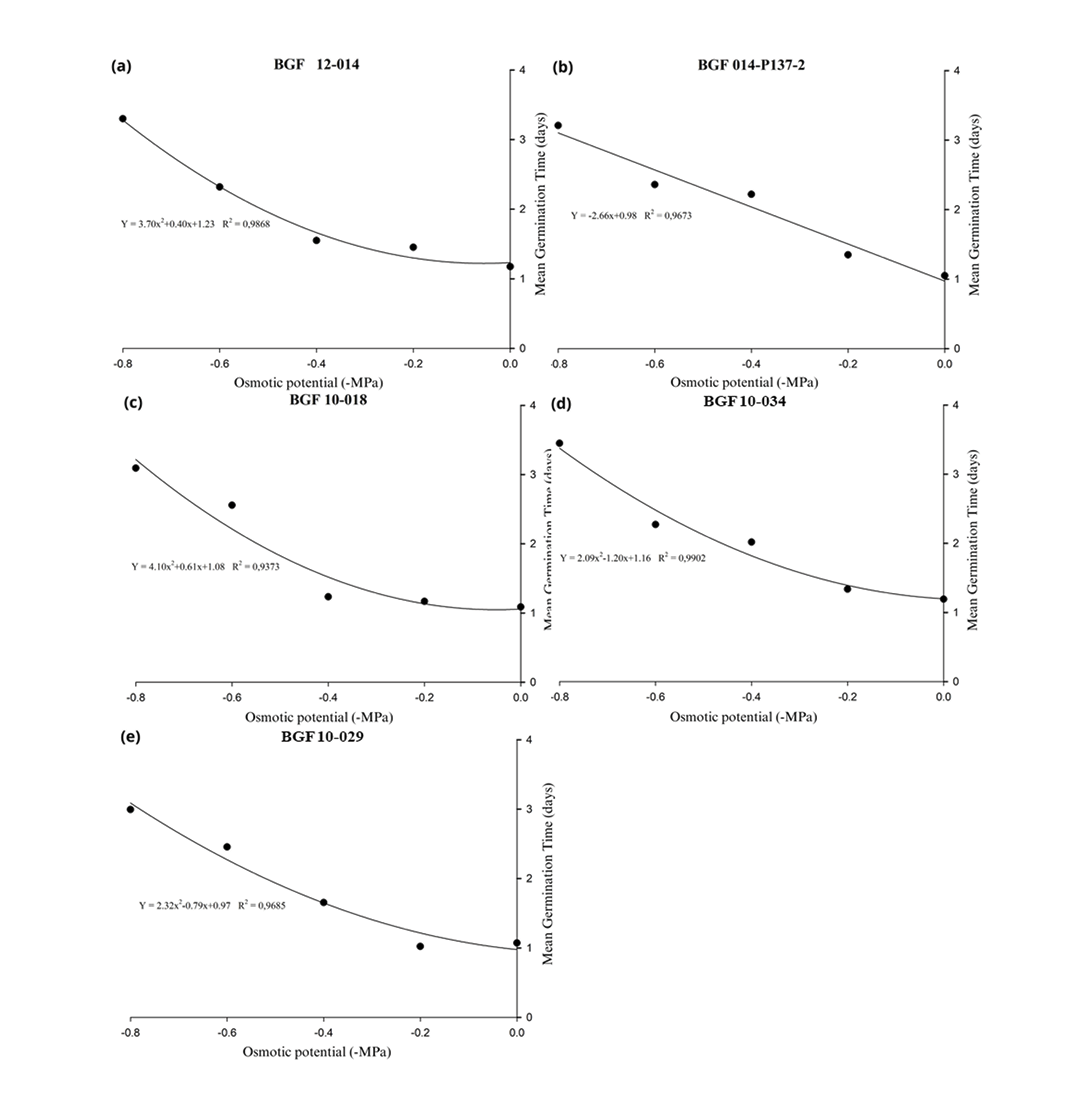

The regression graphs showing the effect of PEG 6000 on MGT of the tested materials are presented in Figure 2. Accession BGF 10-016 did not fit either the linear or quadratic regression models, preventing the construction of a curve to represent the data. Most of the remaining accessions were best described by a quadratic regression model, with determination coefficients (R²) ranging from 93.75% to 99.16%, indicating a strong fit to observed trends. For accessions BGF 014-P137-2 (Figure 2b), BGF 10-034 (Figure 2d), and BGF 10-029 (Figure 2e), significant increases in MGT began to occur at -0.4MPa, indicating that this osmotic potential was already sufficient to delay the germination process in these genotypes. In contrast, for accessions BGF 12-014 (Figure 2a) and BGF 10-018 (Figure 2c), this sharp increase was only observed starting at -0.6MPa, indicating that these materials are less sensitive to osmotic stress compared to the others, as changes in MGT were only triggered under lower water availability conditions.

Additionally, the Scott–Knott clustering test for MGT (Table 4) showed that at osmotic potentials of 0.0, -0.2 and -0.6MPa, the accessions did not differ significantly from one another, indicating similar performances under these environmental conditions. However, at -0.4MPa, accessions BGF 12-014, BGF 10-018 and BGF 10-029 displayed superior MGT values, differing significantly from the other genetic materials, which exhibited higher MGTs, highlighting the variation in sensitivity to water stress among the accessions. At the most negative potential (-0.8MPa), only BGF 10-016 showed a significantly different MGT compared to the others, with a lower mean germination time than the remaining accessions.

Table 4. Mean germination time (MGT) of seeds from Stylosanthes spp. accessions subjected to different concentrations of PEG 6000. Means followed by the same letter in the columns do not differ from each other according to the Scott-Knott test at 5%.

|

Mean germination time (MGT) (days) |

|||||

|

Osmotic Potential (-MPa) |

|||||

|

Accession |

0.0 |

-0.2 |

-0.4 |

-0.6 |

-0.8 |

|

BGF 10-016 |

1.10 a |

1.10 a |

1.72 a |

3.00 a |

1.00 a |

|

BGF 12-014 |

1.17 a |

1.45 a |

1.55 a |

2.32 a |

3.30 b |

|

BGF 014-P137- 2 |

1.05 a |

1.37 a |

2.25 b |

2.40 a |

3.20 b |

|

BGF 10-018 |

1.12 a |

1.15 a |

1.25 a |

2.55 a |

3.10 b |

|

BGF 10-034 |

1.22 a |

1.35 a |

2.02 b |

2.72 a |

3.42 b |

|

BGF 10-029 |

1.07 a |

1.02 a |

1.67 a |

2.40 a |

3.00 b |

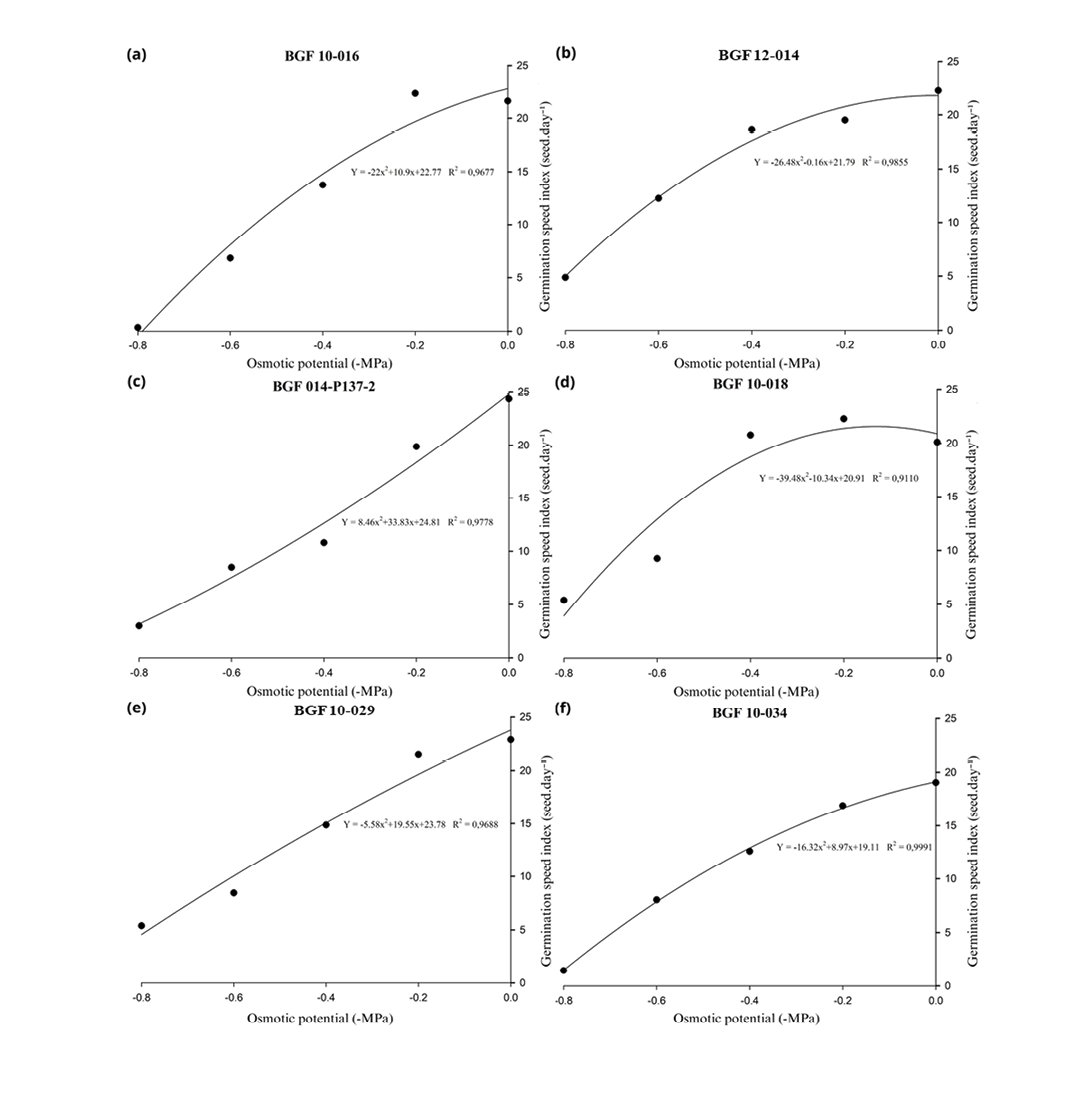

The relationship between osmotic potential and GSI was modelled using quadratic regression equations (Figure 3), with R² values ranging from 0.9110 to 0.9991, indicating a strong dependence of GSI on the osmotic conditions imposed by PEG 6000 treatments. The accessions showed distinct GSI responses as the osmotic potential decreased. Under the control treatment (0MPa), only accession BGF 10-034 exhibited a GSI below 20, while the other accessions showed similar values, approximately at the same level. The fitted equations suggest that the accessions respond differently to water availability, with greater or lesser reductions in GSI as water stress increases across the evaluated materials.

Figure 2. Regression plots showing the effect of different concentrations of PEG 6000 on the mean germination time (MGT) of Stylosanthes spp. accessions. PEG 6000 concentrations were used to simulate water stress, ranging from 0.0 to -0.8MPa. Each point represents the mean of four replications, and the lines represent the fit of the data using a quadratic or linear regression mode. Accession BGF 10-016 is not included in the figure because it did not fit either the linear or quadratic regression models, preventing the construction of a representative curve.

Accession BGF 10-018 (Figure 3d) maintained a high GSI up to -0.4MPa, with a sharp decline only observed at -0.6MPa, standing out as the material with the least variation in GSI as the osmotic potential decreased. Accessions BGF 10-016 (Figure 3a), BGF 10-034 (Figure 3f) and BGF 10-029 (Figure 3e) maintained high GSI values at the two least concentrated PEG levels (0.0 and -0.2MPa) but exhibited significant reductions at -0.4MPa and again at -0.8MPa. Similarly, accessions BGF 12-014 (Figure 3b) and BGF 014-P137-2 (Figure 3c) also showed marked decreases in GSI as osmotic potential declined; however, an osmotic potential of only -0.2MPa was already sufficient to significantly affect the GSI of these genotypes, as this condition caused noticeable differences compared to the control, highlighting that even a slight reduction in water availability is enough to exert a significant influence on this variable.

Figure 3. Regression plots showing the effect of different osmotic potentials on the germination seed index (GSI) of Stylosanthes spp. accessions. PEG 6000 concentrations were used to simulate water stress, ranging from 0.0 to -0.8MPa. Each point represents the mean of four replications, and the lines represent the fit of the data using a quadratic regression mode.

According to the Scott–Knott test (Table 5), variability in GSI among the accessions was evident at each osmotic potential. Under the control condition (0.0MPa), accessions BGF 10-034 and BGF 10-018 had the lowest GSI values, whereas the other accessions had higher GSI means. Moreover, variations in genotype responses were observed across the remaining osmotic potentials. Under the most severe water stress (-0.8MPa), accessions BGF 12-014, BGF 10-018 and BGF 10-029 showed the highest GSI values, standing out under this condition of limited water availability.

Table 5. Germination speed index of seeds from Stylosanthes spp. accessions subjected to different PEG 6000 concentrations. Means followed by the same letter in the columns do not differ from each other according to the Scott-Knott test at 5%.

|

Germination speed index (GSI) (seeds.days-1) |

|||||

|

Osmotic Potential (-MPa) |

|||||

|

Accession |

0.0 |

-0.2 |

-0.4 |

-0.6 |

-0.8 |

|

BGF 10-016 |

21.62 a |

22.33 a |

13.75 b |

6.83 b |

0.35 b |

|

BGF 12-014 |

22.25 a |

19.52 b |

18.64 a |

12.25 a |

4.87 a |

|

BGF 014-P137-2 |

24.37 a |

19.87 b |

10.80 c |

8.50 b |

2.99 b |

|

BGF 10-018 |

20.12 b |

22.30 a |

20.79 a |

9.26 b |

5.39 a |

|

BGF 10-034 |

19.05 b |

16.89 c |

12.60 c |

8.03 b |

1.45 b |

|

BGF 10-029 |

22.89 a |

21.50 a |

14.87 b |

8.45 b |

5.39 a |

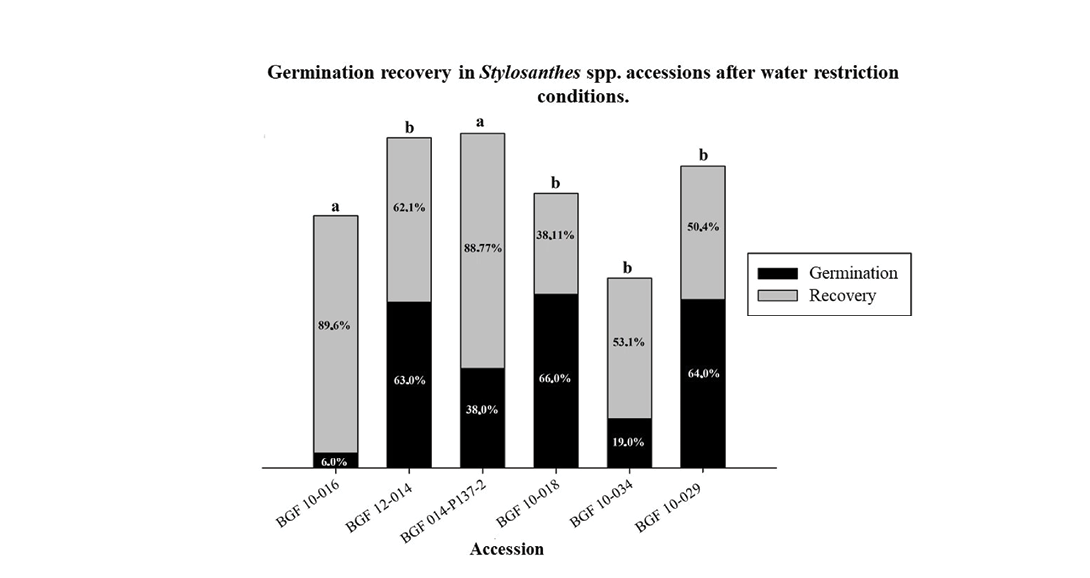

The analysis of variance (Table 6) for the stage referred to as ‘germination recovery’ – which aimed to assess the proportional germination of the remaining seeds from the accessions previously subjected to the most severe water stress treatment (-0.8MPa), now placed in distilled water (0.0MPa) – revealed significant differences among the accessions.

Table 6. Summary of analysis of variance (ANOVA) for germination recovery of Stylosanthes spp. accessions after exposure to water stress at a potential of -0.8MPa. DF, degrees of freedom; REC, germination recovery (%); CV, coefficient of variation; **, significant (p-value < 0.05).

|

Variation source |

DF |

REC |

|

Accession |

5 |

4.78** |

|

Residual |

18 |

|

|

CV (%) |

30.44 |

The Scott–Knott mean grouping test revealed the formation of two distinct groups for germination recovery. Accessions BGF 10-016 and BGF 014-P137-2 exhibited the highest recovery percentages of 89.6% and 88.7%, respectively. All other accessions showed significantly lower recovery rates than these two, highlighting that water stress during the initial germination phase had a significant impact, leading to greater loss of seed viability in these genotypes (Figure 4).

Discussion

The germination percentages at -0.8MPa (Figure 1) confirmed that this concentration of PEG 6000 reduced the number of germinated seeds. Yamashita et al (2018) evaluated the effect of water stress induced by PEG 6000 at different osmotic potentials (0.0; -0.2; -0.4; -0.6; -0.8; and -1MPa) on the germinability of the species Stylosanthes capitata Vogel, and found that the more negative the solution potential, the greater the reduction in seed germination percentage – results that are consistent with those observed in the present study.

Moreover, Braccini et al (1996) explained the reduction effect caused by the use of PEG 6000, who considered the high molecular weight of the substance, its high viscosity, and low O2 diffusion rate as factors that directly impair oxygen availability to seeds during germination. Additionally, Oliveira et al (2017) reiterated that the high viscosity of PEG 6000 is also directly related to the seed’s ability to absorb water, because as the osmotic potential of the solution decreases, the availability of water falls below the level required for seeds to resume metabolic activities and, consequently, for the embryonic axis to grow.

Tolerance to water stress is an important characteristic to consider when recommending genotypes capable of withstanding different osmotic potentials and water scarcity, especially in ecologically challenging areas with low water availability and saline characteristics (Rego et al, 2011). Moreover, plants adapted to such conditions not only survive and establish successfully but also complete their reproductive cycle, ensuring population persistence in harsh environments (Baskin & Baskin, 2014; Nicotra et al, 2010). The BGF-UEFS accessions presented both intra- and interspecific genetic variability, and combined with the fact that they were collected from different locations in the semi-arid region of Bahia (Oliveira and Queiróz, 2016), this may explain the differing germination performances of the Stylosanthes spp. genotypes under water stress induced by PEG 6000, as observed in this study. The genetic materials BGF 12-014, BGF 10-018, and BGF 10-029 were superior to the other genotypes.

The regression analysis for MGT of the accessions (Figure 2) suggested that as PEG 6000 concentration increased, seeds required more time to emit the radicle. Duarte et al (2018), when observing the effect of water stress on the germination of white angico (Anadenanthera colubrina var. cebil (Vell.) Brenan), also found results similar to those of this study, with an increased MGT under lower water availability. This can be explained by the fact that changes in water potential can affect the hydraulic properties of the seed coat, and from this perspective, the lower the potential, the lower the water diffusibility (Antunes et al, 2011). This phenomenon delays water absorption by the seed and, consequently, germination (Bradford 1990; Ávila et al, 2007).

The divergence in MGT results among the accessions may be attributed to genotypic variation, as they originated from different localities and may have different seed physiological qualities. The heterogeneity among them leads to differences in the average MGT (Kolchinski et al, 2005). From an ecological perspective, delayed germination under low water potential can act as a selective filter, favouring genotypes capable of maintaining viability and responding only under favourable moisture conditions (Bradford, 2002). In this regard, accession BGF 10-016 exhibited the most favourable germination pattern under the highest water stress level. However, the low number of germinated seeds in this accession suggests caution in interpreting this result, as the apparent performance may reflect a small number of highly vigorous seeds rather than a consistent tolerance across the seed lot. Moreover, Santos et al (2016), investigating water stress simulated by PEG 6000 in seeds of Caatinga species, Catingueira (Poincianella pyramidalis (Tul.) L. P. Queiroz) and White angico (Anadenanthera colubrina (Vell.) Brenan), observed a higher MGT compared to all Stylosanthes spp. accessions tested in this study at -0.8MPa, being 4.85 and 3.48 days, respectively.

As pointed out by Bewley and Black (1994), when the available moisture is below the necessary level, enzymatic activity is significantly reduced, hindering seed hydration and compromising the ability to metabolize internal reserves. In this sense, the authors emphasized that this phenomenon results in slower and less efficient germination, as water stress limits the biochemical reactions essential for resuming seed metabolism. Therefore, the results of this study are consistent with those reported in the literature, as higher PEG 6000 concentrations led to a reduction in the GSI of the Stylosanthes spp. accessions tested.

Simioni et al (2011) found similar results in sorghum seeds (Sorghum bicolor (L.) Moench) under water deficit conditions, with GSI decreasing from -0.4MPa. The same was observed by Oliveira et al (2017), who analyzed the germination behaviour of cotton genotypes (Gossypium hirsutum L.). Azerêdo et al (2016) also found that water deficit simulated with PEG 6000 at -0.2MPa was sufficient to reduce the GSI of white angico seeds, a species also used in animal feed.

PEG 6000, owing to its high molecular weight, cannot penetrate seed structures and thus only limits water availability (Marcos Filho, 2002). Accordingly, Marcos Filho (2002) also noted that, since it does not exert toxic effects on the seeds, those that tolerate this temporary interruption in water supply during germination can survive and germinate when moisture becomes favourable. This explains the recovery of germination in some genotypes evaluated in this study. The differences observed among them may be attributed to genotypic variation, as some genotypes may not tolerate partial hydration. In such cases, metabolic activity may be initiated and then halted, where the continued lack of water becomes crucial for maintaining seed viability and successful germination.

This study highlights the variability among BGF-UEFS genotypes in terms of their performance under water stress conditions.

The results enhance our understanding of germination dynamics under water-limited conditions and reveal significant variability among Stylosanthes spp. accessions. This variation is particularly important for identifying promising genotypes with potential use as forage resources in semi-arid environments, where water scarcity poses a major challenge to seedling establishment and pasture productivity. While these findings provide valuable insights into early responses to water stress, further research is needed to assess the agronomic potential of these accessions under field conditions. Field trials or common-garden experiments represent a logical next step to evaluate seedling establishment, early plant development, and overall performance in more variable and realistic environments. Such approaches are essential for selecting resilient accessions suitable for forage production systems facing increasingly unpredictable climatic conditions.

Conclusion

The Stylosanthes spp. accessions from BGF-UEFS exhibited different germination performances under water stress conditions for the variables G%, MGT and GSI.

The evaluated germination parameters of the Stylosanthes spp. accessions were negatively affected by the reduction in osmotic potential.

Accessions BGF 012-014, BGF 10-018 and BGF 10-029 were the most promising due to their performance in the evaluated germination parameters under water stress, simulated by PEG 6000, during the initial germination phase.

Author contributions

VOS was responsible for conceptualization and methodology. VOS, AAS, and RJS handled data collection, while VOS and RJS also performed formal analysis. VOS and UCO wrote the original draft. MNN and CRP focused on methodology and visualization. VOS, UCO, MNN, and CRP performed revision and editing. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge FAPESB (Foundation for Research Support of the State of Bahia) for financial support during the execution of this work.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors report no known financial or personal conflicts of interest that could have affected the research or findings presented in this article.

References

Antunes, C. G. C., Pelacani, C. R., Ribeiro, R. C., Souza C. L. M., Castro R. D. (2011). Germinação de sementes de Caesalpinia pyramidalis Tul. (catingueira) submetidas a deficiência hídrica. Revista Árvore. 35, 1007-1015. doi: https://doi.org/10.1590/S0100-67622011000600006

Ávila, M. R., Braccini, A. L., Scapim, C. A., Flagiari, J. R., Santos J. L. (2007). Influência do estresse hídrico simulado com manitol na germinação de sementes e crescimento de plântulas de canola. Revista Brasileira de Sementes. 29, 98-106. doi: https://doi.org/10.1590/S0101-31222007000100014

Azerêdo, G. A., Paula, R. C., Valeri, S. V. (2016). Germinação de sementes de Piptadenia moniliformis Benth. sob estresse hídrico. Ciência Florestal. 26,193-202. doi: https://doi.org/10.5902/1980509821112

Bewley, J. D., Black, M. (1994) Seeds: physiology of development and germination (New York: Plenum), 445p.

Braccini, A. L., Ruiz, H. A., Braccini, M. C.L., Reis, M. S. (1996). Germinação e vigor de sementes de soja sob estresse hídrico induzido por soluções de cloreto de sódio, manitol e polietileno glicol. Revista Brasileira de Sementes. 18, 10-16.

Bradford, K. J. (1990). Influence of water stress on seed germination rate in Cucumis sativus. Plant Physiology, 80, 351–357. doi: https://doi.org/10.1104/pp.94.2.840

Bradford, K. J. (2002). Applications of hydrothermal time to quantifying and modeling seed germination and dormancy. Weed Science 50, 248–260. doi: https://doi.org/10.1614/0043-1745(2002)050[0248:AOHTTQ]2.0.CO;2

Baskin, C., Baskin, J.M. (2014). Seeds: Ecology, Biogeography, and Evolution of Dormancy and Germination. Academic Press, 8, 150-162.

Canzi, G. M., Gai, V. F., Souza, G. B. P., Effting, P. B. (2021). Adubação nitrogenada sobre a produtividade do Stylosanthes Campo Grande em solo argiloso. Revista Cultivando o Saber. 14, 86-94.

Duarte, M. M., Kratz, D., Carvalho, R. L. L., Nogueira, A. C. (2018). Influência do estresse hídrico na germinação de sementes e formação de plântulas de angico branco. Advances in Forestry Science. 5, 375-379. doi: https://doi.org/10.34062/afs.v5i3.5521

Flora e Funga do Brasil. Stylosanthes. Jardim Botânico do Rio de Janeiro. Available at: https://floradobrasil.jbrj.gov.br/FB115.

Gómez-Campo, C. (2006) Long-term seed preservation: updated standards are urgent (Spain: Universidad Politécnica de Madrid, 168p.

Gonzalez, L. M., Lopez, R. C., Fonseca, I., Ramirez, R. (2000). Growth, stomatal frequency, yield and accumulation of ions in nine species of grassland legumes grown under saline conditions. Pastos y Forrajes. 23, 299-308. doi: https://doi.org/10.5555/20013029138

Gusha, J., Halimanti, T. E., Kantsandes, S., Zvinorova, P. I. (2015). The effect of Opuntia ficus-indica and forage legumes-based diets on goat productivity in the smallholder sector in Zimbabwe. Small Ruminant Research. 125, 21-25. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.smallrumres.2015.02.018

Habermann, E., Oliveira, E. A. D., Delvecchio, G., Belisário, R., Barreto, R. F., Viciado, D. O., Rossingnoli, N. O., Costa, K. A. P., Prado, R. M., Gonzalez-Meler, M., Martinez, C. A. (2021). How does leaf physiological acclimation impact forage production and quality of a warmed managed pasture of Stylosanthes capitata under different conditions of soil water availability? Science of the Total Environment. 759, 143505. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.143505

Hussain, H. A., Hussain, S., Khaliq, A., Ashraf, U., Anjum, S. A., Men, S., Wang, L. (2018) Chilling and Drought Stresses in Crop Plants: Implications, Cross Talk, and Potential Management Opportunities. Frontiers in Plant Science. 9, 1-21. doi: https://doi.org/10.3389/fpls.2018.00393/full

IBGE – Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatística (2018) Novo Censo Agropecuário mostra crescimento de efetivo de caprinos e ovinos no Nordeste. Avaliable at: https://www.embrapa.br/cim-inteligencia-e-mercado-de-caprinos-e-ovinos/busca897de-noticias//noticia/36365362/novo-censo-agropecuario-mostra-crescimento-de-efetivo-de-caprinos-e-ovinos-no-nordeste.

IBGE – Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatística (2023) Brasil em síntese. Avaliable at: https://brasilemsintese.ibge.gov.br/territorio.html.

Kolchinski, E. M., Schuch, L. O. B., Peske, S. T. (2005). Vigor de sementes e competição intraespecífica em soja. Ciência Rural. 35, 1248-1256. doi: https://doi.org/10.1590/S0103-84782005000600004

Laboriau, L. G.; Valadares, M. B. (1976). On the germination of seeds of Calotropis procera. Anais da Academia Brasileira de Ciências, 48, 174–186.

Labouriau, L. G. (1993). A germinação das sementes (Washington: OEA), 174 p.

Lawlor D. W., Cornic G. (2002). Photosynthetic carbon assimilation and associated metabolism in relation to water deficits in higher plants. Plant, Cell & Environment, 25(275-294). doi: https://doi.org/10.1046/j.0016-8025.2001.00814.x

Liu, P., Huang, R., Hu, X., Jia, Y., Li, J., Luo, J., Liu, Q., Luo, L., Liu, G., Chen, Z. (2019). Physiological responses and proteomic changes reveal insights into Stylosanthes response to manganese toxicity. BMC Plant Biology, 19, 202–223. doi: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12870-019-1822-y

Maguire, J. D. (1962). Speed of germination-aid in selection and evaluation for seedling emergence and vigor. Crop Science, 2,176-177. doi: https://doi.org/10.2135/cropsci1962.0011183X000200020033x

Marcos Filho, J. (2002). Fisiologia das Sementes de Plantas Cultivadas. (Brazil: Fealq), 237p.

McKeon, G.M. (1985). Pasture seed dynamics in a dry monsoonal climate, II The effect of water availability, light and temperature on germination speed and seedling survival of Stylosanthes humilis and Digitaria ciliaris. Australian Journal of Ecology, 10, 149-163. doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1442-9993.1985.tb00876.x

Michel B.E., Kaufmann, M.R. (1973). The osmotic potential of polyethylene glycol 6000. Plant Physiology, 5, 914–916. doi: https://doi.org/10.1104/pp.51.5.914

Nicotra, A. B., Atkin, O. K., Bonser, S. P., Davidson, A. M., Finnegan, E. J., Mathesius, U., Poot, P., Purugganan, M. D., Richards, C. L., Valladares, F., & van Kleunen, M. (2010). Plant phenotypic plasticity in a changing climate. Trends in Plant Science, 15, 684–692. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tplants.2010.09.008

Oliveira, H., Nascimento, R., Leão, A. R., Cardoso, J. A. F., Guimarães, R. F. B. (2017). Germinação de sementes e estabelecimento de plântulas de algodão submetidas a diferentes concentrações de NaCl e PEG 6000. Revista Espacios. 38, 13. doi: https://doi.org/10.5555/19621604893

Oliveira, R. S., Queiroz, M. A. (2016). GENETIC DIVERSITY IN ACCESSIONS OF Stylosanthes spp. USING MORPHOAGRONOMIC DESCRIPTORS. Revista Caatinga. 29, 101-112.

R Core Team (2024). R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. Avaliable at: https://www.R-project.org/

Rego, S. S., Ferreira, M. M., Nogueira, A. C., Grossi, F., Sousa, R. K., Brondani, G. E., Araujo, M. A., Silva A. L. L (2011). Estresse hídrico e salino na germinação de sementes de Anadenanthera colubrina (Velloso) Brenan. Journal of Biotechnology and Biodiversity. 2, 37- 42.

Roberts, E. H. (1973). Predicting the storage life of seeds. Seed Science and Technology. 1, 499-514. Santos Júnior, S. R. A, Pelacani, C. R., Santos, V. O., Silva, A. A., Fernandes, S. M., Gissi, D. S., Oliveira R. S. (2022). Banco de Germoplasma de Forrageiras da Universidade Estadual de Feira de Santana (BGF-UEFS). Revista RG News. 8, 5-15.

Santos, C. A., Silva, N. V., Walter, L. S., Silva, E. C. A., Nogueira, R. J. M. C. (2016). Germinação de duas espécies da caatinga sob déficit hídrico e salinidade. Pesquisa Florestal Brasileira, 36, 219-224. doi: https://doi.org/10.4336/2016.pfb.36.87.1017

Silva, A. A., Pelacani, C. R., Grilo, J. S. T. F., Pereira, L. S., Oliveira, R. S. (2024). Analysis of dormancy and physiological quality of Stylosanthes spp. Stored in FGB-UEFS. Revista Ceres. 71, 1-7. doi: https://doi.org/10.1590/0034-737X2024710012

Simioni, T. A., Gomes, F. J., Teixeira, U. H. G., Fernandes, G. A., Botini, L. A., Mousquer, C. J., Costa, J. W. R., Hoffman, A. (2014). Potencialidade da consorciação de gramíneas e leguminosas forrageiras em pastagens tropicais. PubVet. 8, 1551-1697. doi: https://doi.org/10.22256/pubvet.v8n13.1742

Simões, W. L., Oliveira, A. R., Guimarães, M. J. M., Silva, J. S., Oliveira, C. R. S., Voltolini, T. V., Barbosa, K. V. S. (2022). Arranjo populacional do sorgo forrageiro irrigado para um cultivo eficiente no Semiárido brasileiro. Brazilian Journal of Development. 8, 16305-16320. doi: https://doi.org/10.34117/bjdv8n3-053

Scott, A. J., Knott, M. A. A. (1974) A cluster analysis method for grouping means in the analysis of variance. Biometrics. 30, 507-512.

Souza, R., Hartzell, S., Feng, X., Dantas, A. C., Souza, E. S., Menezes, R. S. C., Porporato, A. (2020). Optimal management of cattle grazing in a seasonally dry tropical forest ecosystem under rainfall fluctuations. Journal of Hydrology. 588, 125102.

Villela, F. A., Doni Filho, L., Sequeira, E. L. (1991). Tabela de Potencial Osmótico em Função da Concentração de Polietilenoglicol 6.000 e da Temperatura. Pesquisa Agropecuária Brasileira. 26, 1957-1968.

Yamashita, O. M., Petry, R. D. S., Baio, F. H. R., Roque, C. G., Camillo, M. A., Carvalho, R. D. (2012). Stylosanthes capitata germination response to environmental and chemical stimulus. Gaia Scientia, 12, 161-169.

Zambão, J., Bittencourt, H. H., Bonome, L. T. S., Trezzi, M. M., Fernandes, A. C. P.P. (2020). Water restriction, salinity and depth influence the germination and emergence of sourgrass. Planta Daninha. 38, 1-9. doi: https://doi.org/10.1590/S0100-83582020380100057