What farmers value matters for the management of local breeds: A case study of the Pyrenean goat breed

Anne Lauviea,*, Marie-Odile Nozières-Petita, Fanny Thuaultb,c, Nathalie Couixd,e

a SELMET, Univ Montpellier, CIRAD, INRAE, Institut Agro, Montpellier, France

b Association La chèvre de race Pyrénéenne, Foix, France

c Present affiliation: AREDEAR Occitanie, Foix, France

d AGIR, Université de Toulouse, INRAE, Castanet-Tolosan, France

e Present affiliation: LESSEM, INRAE, Grenoble, France

* Corresponding author: Anne Lauvie (anne.lauvie@inrae.fr)

Abstract: Local breeds are often kept in farming systems where their locally adapted traits are an asset. The agroecological transition movement has brought renewed interest in these breeds with their locally adapted traits. Better understanding the factors underpinning trait preferences of local-breed goat farmers can inform efforts to manage genetic diversity and animal selection. This article examines what goat farmers value in their animals to gain a better understanding of their decisions and expectations. Based on evidence from 20 interviews with farmers using the local Pyrenean goat breed, we show that although breeders attach importance to various animal performance factors, hardiness consistently stands out as a key value. We also show that they attach importance to other factors, such as animal diversity, temperament and appearance (breed standard and aesthetics). Breeders relate to their animals in a way that mobilizes senses, feeling, experiential or emotional dimensions more than just a set of hard traits, and when breeders voice what they value and how that value manifests in practice, their narratives translate the importance of balance and trade-offs.

Keywords: Local breeds, goats, France, hardiness, values

Introduction

Livestock selection must address new challenges around animal genetics to move the agroecological transition forward. The genetics community highlights the need to design breed selection programmes with specific objectives, such as resilience, relevant for livestock in transition toward agroecology. Additionally, they should consider the reduced control over environmental conditions in agroecological farming systems (Phocas et al, 2016). There is consequently growing interest in efforts to improve breed hardiness and integrate diverse objectives that combine a wider set of traits (for example, production-related traits with traits tied to reproduction, survival, health and welfare). Animal genetics is experiencing a fast-paced change in methodologies, with the development of genomics soon to be followed by high-throughput genotyping and phenotyping workflows (Boichard et al, 2015).

Local breeds, and especially those with smaller populations, have been relatively sidelined from selection programmes that have focused on dominant breeds. However, local-breed animals often thrived in farming systems such as agropastoralism, where their locally adapted traits and hardiness proved an asset (Moulin and Perucho, 2023). The agroecological transition movement has brought renewed interest in these breeds with their locally adapted traits (Dumont et al, 2013).

For any goat farm, deciding which breed or breeds to select as a starting point and deciding which individual animals to use to produce the next generation are pivotal decisions that shape and scaffold a coherent production system (Vissac, 2002). Better understanding the factors underpinning these trait-preference decisions of local-breed farmers can valuably inform the work of geneticists who deliver the tools and strategies driving genetic selection programmes. What the farmers want and expect to see in their herds – in other words, what they value in each animal – is a key factor driving these decisions. However, beyond the market value of their products that fundamentally drives revenues, local breeds – more than other breeds – are attributed a variety of other values that reflect each breeder’s relationship with individual animals from that breed and with the breed itself (Couix et al, 2023). We posit that examining these values can bring key insights to inform the design of genetic resources management programmes geared to address the challenges facing livestock farming today. This inquiry is especially relevant in the case of local and rare breeds investigated here, as they have so far remained sidelined from the big selection programmes but are now attracting renewed interest to help agroecological transition move forward.

Here we addressed these challenges by studying farmers’ objects of value around the local and rare Pyrenean goat breed from south-western France.

The Pyrenean goat is a local breed that farmers have progressively abandoned. A Pyrenean goat conservation organization was created in 2004, and Pyrenean goat numbers today amount to just 5,000 animals kept by around 200 farmers, mostly in farms across the French Pyrenees (Pyrenean goat breed association, 2024a). In 2023, most of the farmers (207) were situated in the two regions concerned by the Pyrenean Mountain range, Occitanie and Nouvelle-Aquitaine regions. Twenty-two flocks were located in other French Regions (Pyrenean goat breed association, 2024b). About a third of these farmers raise their flock for milk and cheese. The remaining two-thirds produce kid meat, often alongside other farm products or additional professional activities (‘pluriactivity farmers’). The Pyrenean goat exhibits strong phenotypic variability, especially in terms of colour. A breed standard describing the defining traits was adopted in 2008 (Pyrenean goat breed association, 2024a).

Adopting the same kind of pragmatist stance as Couix et al (2023), we considered value formation as a series of what John Dewey (1939) theorized as valuation processes, where the formation of values spans both the immediate valuing appraisal and the higher-level evaluation (Bidet et al, 2011) and considers the dynamic dimension of values as they change over the course of time and in the course of action. This led us to examine both the way farmers appraise and qualify the animals they tend, and the related livestock farming practices. Consequently, the aim of this article was to study what goat farmers value in their breed and in their animals.

First, we present the approach adopted, which is based on analyzing evidence captured through interviews. We then show that the farmers voiced a diversity of objects of value that accommodate diverse biological and even non-biological traits beyond pure animal performance factors – and thus reveal a diversity of values. We then discuss how the diverse values attached to local-breed animals, driven by the farming system in which they are raised, can help inform strategies for addressing the challenges in managing farm-animal genetic resources.

Materials and methods

Theoretical background

We based our work on 20 semi-structured interviews led in 2021 with Pyrenean goat farmers. The objective of this analysis was to sift through their discourses to identify how the values they attach to their individual animals and the animal breed are formed (Lauvie et al, 2022). Here we mobilized John Dewey’s theory of valuation (Dewey, 1939), which posits that values are shaped by projected consequences of actions (the means) led – in this case, by the goat farmers – to bring about desirable outcomes (the ends). We therefore focused our attention on what farmers said they wanted and expected to see in their flock animals, in other words, what they valued in each animal. However, we went beyond simply surfacing the diversity of sources of value that emerged from farmers’ discourses, to focus on what they told us about how this diversity of values manifests into practice, especially when they connected their expectations of the animals to practices they employ to get a flock that suits them. We also attended to what they said about the responses they saw in the animals. John Dewey (1939) argued that values are not immutable but always potentially open to revision as they can be made to change in the course of interactions between individuals and their environment. Consequently, we also prepared to focus on the way farmers revised their objects of value in response to interactions with their animals.

Data collection

In order to capture ‘what farmers value’ in their work with a local breed, we collected data using a process designed to capture the diversity of farming situations found in our case study. We selected the sample of farmers to cover various criteria. These included the diversity of geographical configurations, by choosing farmers in different locations, and both dairy systems and suckling systems. The sample included mainly Pyrenean goat breed association members, as well as non-members and former members. Additionally, it included breed-association board or committee members, and farmers with varying lengths of experience with Pyrenean goats. The interview guide helped to collect focused data on the history of the goat farm, the reasons that prompted the farmer to choose the Pyrenean goat and flock management system – particularly reproduction and culling/replacement – and the farmer’s relationship with the Pyrenean goat breed association.

A student (senior internship), under the supervision of the authors, performed 20 interviews: 11 with suckling-system farmers and 9 with dairy-system farmers. The vast majority of the farmers surveyed (i.e. 16 out of 20) were members of the Pyrenean goat breed association. Six of the interviews were attended by two people from the farm (goatherd, partner or associate) who conferred and spoke together. One of the interviews led into further exchange with a second (former) farmer (who worked on another farm) who joined the first interviewee. We counted these two exchanges as two separate interviews. All the interviews were recorded and transcribed, except one which was the object of a very detailed report. An interdisciplinary and transdisciplinary team supervised the student and later conducted the analysis presented in this paper (two researchers in animal sciences with a systemic approach, one researcher in organization sciences and the person in charge of the facilitation and extension for the Pyreanean goat breed association).

Data analysis

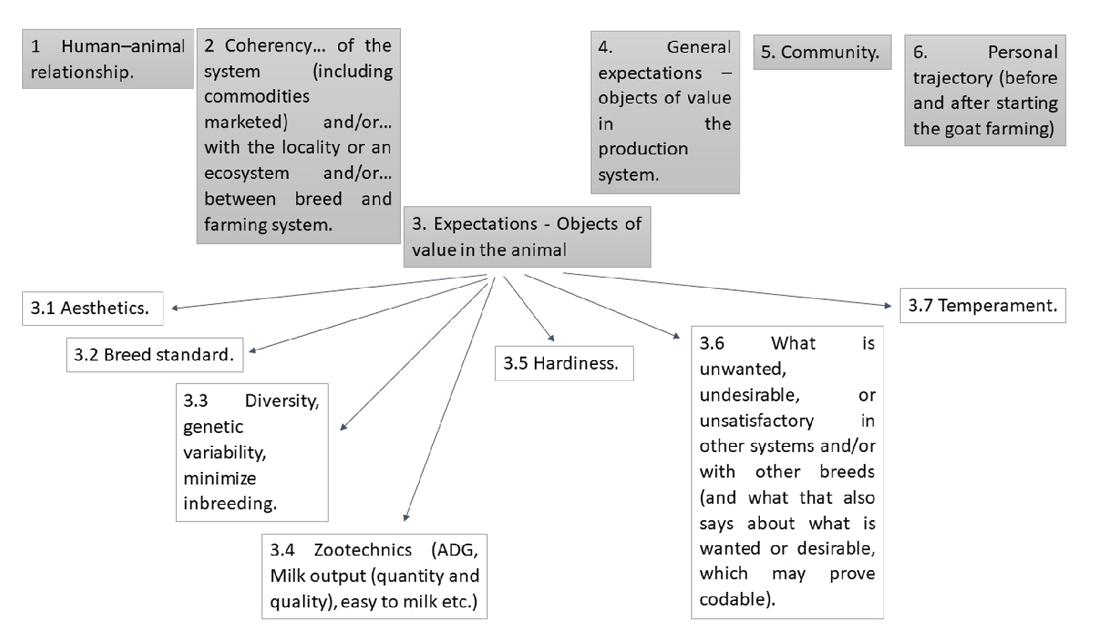

We explored the qualitative interviews by coding the data using NVivo v11 software to develop themes. Coding produced the six themes that feature in the node map in Figure 1, and each of these six themes contained subthemes. Here, we focused our analysis more specifically on the core theme tagged ‘objects of value in the animal’ and its node-mapped subthemes (see Figure 1).

We did not set out to work on speech as an object, but like Macé, we considered spoken discourse as a space that operates connections and attachments and therefore warrants attentive analysis (Macé, 2021). It is for this reason that here, unlike in most livestock science papers, we organized the presentation of our results around verbatim content. The original versions of those verbatim (in French) are available as Supplemental Material 1.

Results

Diverse considerations attached to animal performance factors

Farmers have varied expectations regarding milk yield

The farmers who saw milk yield as an object of value in the animals referred to both milk quantity and milk quality. Certain farmers mentioned milk protein yields or milk fat yields, whereas others referred to a more global, end-in-view criterion, i.e. cheese yield, which in some cases they connected to specific milk parameters and, therefore, to frames of evaluation involving other, non-yield-related criteria. One farmer, for example, talked about the acidity of their flock’s milk, while another – likely inspired by a previous study in the same breed – cited casein polymorphism in their flock’s milk, and several farmers spoke about the taste of the milk as a dimension of milk quality. Still connected to milk production but going beyond quantitative and qualitative traits of milk output, some farmers stated that they attached importance to having goats that were easy to milk, which they sometimes connected to udder conformation, but sometimes not.

Looking at the process of evaluation for these objects of value, certain farmers talked about their own criteria, especially on milk quality, while others also mentioned the standardized national milk test records system called ‘contrôle laitier’ that some saw as a valuable tool for community-wide Pyrenean goat breed conservation and management efforts. On a farm, they highlighted that the milk records tool provided benefits for the wider breed community as well as for their own personal management.

Lastly, certain interviewees explained the link between the performance of their animals and their flock management decisions:

“This year, well, increasingly, but especially this year, maybe because we give alfalfa now, as we have an alfalfa plot, but it’s now 30–40 crottins [type of cheese] a day. With no weight differential. That’s a huge yield right there.”

Meat production: it’s not just average daily gain that counts

Farmers also emphasized the importance of factors related to kid meat production. These factors include size, weight, growth and conformation, which one farmer summed up as the need to have kids “that grow out well”. These size and conformation factors that work towards zootechnic performances were sometimes more or less explicitly verbalized as connected to the breed standard, which we discuss in further detail below. Some farmers attached importance to more specific criteria, such as birth weight, minimum expectations on liveweight at a given age milestone, average daily gain (ADG), or carcass weight.

As seen above for milk yield, certain interviewees explained the link between the performance of their animals and their flock management decisions:

“Because if you care for your does, then the kid will automatically birth big, so you weigh it. It might weigh 5 kg at birth or 3 depending on how you’ve cared for the doe”.

Coherency between conformation and dairying: a challenge for a breed claimed as dual-purpose?

The Pyrenean goat farmers studied here have the option of running a dairy system or a suckling system, as the breed is considered dual-purpose. However, certain farmers mentioned that, in the past, the breed had to navigate periods of tension between the two production uses that proved challenging to manage as a community:

“In fact, the buck committee1 was originally set up about 10 or 15 years ago when everyone in the breed association realized that divisions were emerging between the dairy farmers who only wanted to select for milk, and the suckling systems farmers who only wanted to select for type”.

Several farmers advanced a linkage here between kid health and/or growth and milk quality of the nursing does. For instance, one farmer, who farms their flock for milk and cheese, said:

“Kid growth […] is important [to consider] because if the mother is giving milk packed with protein, then I reckon the kid is also going to grow out a lot faster. So that’s another way [suckling system farmers] can look at it, even if they’re not dairying”.

Another farmer formulated the same idea in a different way:

“But a dairy breed and a meat breed are just the same thing. Because goats that produce the most meat also give the most milk. That’s just common sense.”

Prolificacy: a flock trait framed by the system

The last category of animal-factor performances that farmers discussed is prolificacy of the flock, which is a trait one farmer actively worked on:

“For does farmed 100% free-range and browsing a ‘nutrient-poor’ environment […] prolificacy isn’t even two. So, for me, if there was something to improve my production, it would be about that, some improvement in prolificacy”.

However, high prolificacy is not always a preference, and farmers are conscious that it comes with limits:

“We have a crazy-high prolificacy rate, which has downsides too, because we end up with triplets. We’ve had triplets making up 30% of the herd, and that’s not great. […] it screws up the lactation cycles, the animals are exhausted, and then you have triplet kids weighing in at 4kg.”

Hardiness is valued as a constant

A notion that accommodates a diversity of traits

Hardiness was a term widely used by the farmers interviewed, and for many, it was one of the features that led them to choose the breed, and sometimes even the first factor they mentioned. One farmer put it in these terms:

“Ah! Hardiness! Well, that’s what we like about the Pyrenean goat, its hardiness. It can eat woody brush, and never really get sick. Hardiness means goats that range and graze what they need, never getting sick, kept outside all the time – you just arrange to bring them in for kidding, and that’s pretty much it, that’s what we want.”

When expanding on what they mean by hardiness, the farmers talked about a wide range of abilities: ability to range and use all vegetation resources available on the farm, ability to stay outside even in harsh weather, ability to mother their kids, ability to take care of their own needs, ability to tolerate parasitism problems and health problems in general, and so on. Certain abilities, such as ranging widely and using all vegetation resources available on the farm, were more widely recognized among breeders. Depending on farmers, various abilities were emphasized in different ways.

A notion that pulls together animal–environment–herd management factors

Several farmers made a connection between their vision of hardiness and their animal management practices or even their livestock system performance goals, with one farmer asserting that:

“It’s that opportunity to exploit that hardiness, with prospects for saving on costs, that ultimately pushed me to look for the friction point that would mean it ends up making economic sense”.

Some farmers talked about the benefit of finding a compromise between animal-factor performances and hardiness, as illustrated here:

“Obviously, you need your animals [...] to give you enough milk to get by, to make a livelihood, put food on the table. That’s your bottom line – the rest is just about finding the right compromise, the right balance. But for us it’s also super important to have well-adapted animals that will happily stay outside without any kind of problems”.

Certain interviewees also underlined that hardiness drives animal-factor performances. For example, one farmer made the connection between the ability to use specific resources and production performances:

“It would be a hardy goat, that has learnt very young to range for all the food around in its environment, like woods, brush and wildland, and yet still manages to give you a goodish ADG.”

An important feature of this notion of hardiness is that it is tightly connected to how the animals are managed, such as free-ranging for example, or in resource-squeezed systems, and some farmers also make the connection to local range habitat, such as this farmer who explained:

“The breed is adapted to our work conditions and the local topography, even if today […] it’s been raining non-stop for a month now, and there’s no other breed that could withstand the wet like she did, that’s for sure. Plus, it’s a goat that uses little if any bought feed, so it’s pretty cheap to keep.”

Hardiness as all-round self-sufficient animals

Finally, in addition to underpinning a range of abilities and traits linked to farm-system conditions, the notion of hardiness was also articulated in more global approaches that refer to what might be described as self-sufficiency, i.e. the fact that the animals demand less human care and attention, and fend for themselves:

“Hardiness also means needing as little care from us as possible.”

One of the farmers surveyed expanded on this idea by bringing the domestication factor into play:

“That’s what it is: livestock that can... Listen, I’d be exaggerating if I thought my goats could happily live without me, I don’t think they could, because there’s been some domestication. They are only there to collaborate with me. But my goats can stay outside without getting infested with parasites”.

Note that this self-sufficiency can also be identified as a specific trait in a given animal, in which case it makes that individual animal particularly valued. In one interview, when the interviewer and farmer were standing facing the flock and the farmer was asked which of the goats had the most merit, the farmer answered:

“I think it’s the white one with the black neck. Her name is [name of the goat]. In milk, hair, type, hardiness, easy, stood in the middle of the herd, never needing special care. She just blends in, so independent that... Well, for me, that’s a good balance, a good compromise.”

This self-sufficiency also overlaps into a degree of stubbornness, resistance or refusal to yield to human command – a point touched upon by a farmer:

“It’s that part of hardiness that has its downsides. Just try and separate the kids at birth, and see how far you get! Nowhere! There’s just no way!”.

On the same farm, the following testimony explained why they aim for and prize self-sufficiency:

“Like us, an animal will adapt to indoor comfort, but we just cannot keep them penned up indoors around the clock. It’s just impossible. They would turn violent. They’re too accustomed to being outside… […] We favour that. Because they need to know how to go out and forage, find their own food. Look, here’s your proof: we give them a yoghurt pot of barley, it’s there on offer, and they don’t even look at it. Zero cereal feed”.

Note that in this case, the fact that the goats resist the farmers’ command is considered a valued trait.

Other objects of value beyond zootechnical traits

Diversity valued in and of itself

While one farmer spoke of how milk yield in his flock was widely heterogeneous and how they wanted to bring about more homogeneity by removing the less milk-driven stock, most of the farmers who talked about intra-breed diversity approached the issue from the angle of working to conserve this genetic diversity:

“Otherwise, you are also impoverishing the gene pool. Because if we keep pushing the population through a funnel, one day we’ll end up with clones”

or again:

“Because I really liked those animals, plus I’m naturally for conservation and against losing stuff, like agricultural diversity and even biological diversity in general. [...] But there’s also the fact, when you’re working on a local breed, you have to be really careful not to bottleneck the population. Which means you just can’t let any family die off. It’s our job to improve every goat – even poor ones. That’s part of what the conservation effort is about – taking a poor goat and improving it. Sometimes it drags on, and sometimes nothing works. There are bad families, hopelessly bad families. [….] That said, for me, there’s that overriding criterion of vital genetic variability, as you really can’t let any family disappear, because a breed that counts just 4,000 animals is a desperately vulnerable breed.”

The farmer in that last example, like others interviewed, voiced the fact that they are ready to push less hard on animal performance criteria in order to conserve the breed’s genetic diversity. One farmer said they used to inbreed heavily, but got to a point where they needed to “look around elsewhere”.

Importance attached to the animal’s temperament

The animal’s behaviour and temperament proved to be equally important objects of value, and the farmers often frame these traits in terms of the type of human–animal relationship they potentiate, whether positive or negative. This is seen in the words of one farmer, who said:

“[At the] close of the season, we set away three goats, one of which, [name of a goat], is at practically 2L. We just can’t get along at milking. She’s a right bitch! […]. Outside of milking, she’s great, but at milking, […] she just straight refuses.”

Another puts it in these terms:

“As a rule, the one I like best is the one that communicates the most, the one you share most with, the one you call by first name.”

These temperament factors can also be gain importance depending on the types of activities carried out on the farm. One farmer, for instance, highlighted how the goats play a doubly important role because they host visitors on his farm.

The appearance factor: between breed standard and aesthetic preferences

The farmers’ accounts featured a substantial number of references to the animal’s appearance, either in terms of the breed standard or ‘type’, i.e. the defining physical traits of the breed, or in terms of the aesthetics factor. Note that several farmers employed the adjective ‘beautiful’ for both type-related and aesthetics-related traits:

“This year we’ve had several newborns that really are beautiful. When I say beautiful, I don’t just mean beautiful as in pretty to look at. I mean, they also show good conformation, real potential... In terms of breed standard and such.”

Farmers who explicitly mentioned the breed standard sometimes voiced the fact that it was co-constructed by collective agreement, and one interviewee distinguished a component based on personal criteria, on top of the other foundational criteria that had been set by the breed community:

“That’s personal criteria, not Pyrenean goat breed criteria.”

Note too that several farmers outlined how these breed-standard criteria or breed-type criteria are in flux and workable, and that they aim to improve that dimension in their own flocks.

Several farmers prized the aesthetics factor of the breed, as shown in this exchange:

“And I just fell in love with the breed. Instantly. The beautiful coat, the lovely long hair, the body form. Plus the fact that it’s threatened with extinction – that was added motivation.”

Traits that farmers attach aesthetic importance to or say are a part of what makes the animals beautiful include not just the striking horn set and coat colouring (sometimes with a preference for a palette of colours) but also, for example, the ears, the hair, and the shape of the head or the legs. Some statements also referenced an aesthetics of the goat roaming free outside. One farmer said:

“They are prettier when they are ranging free, that’s where they are beautiful.”

And another said:

“Outside they ’re just magnificent”.

It is noteworthy that the role of the senses, feelings, the experiential and/or emotional dimensions emerge strongly in these accounts.

What breeders value: how valuation processes involve more than just hard traits

The experiential and emotional dimensions in livestock farming practice

The previous paragraph, highlighting the aesthetics factor in goat farming, clearly reveals a prominent role of senses or feelings to the goat farmers’ decisions. The responses to questions addressing what farmers want and expect to see in their animals also expressed more holistic considerations tied to all-around satisfaction with goat farming. In other words, the farmers’ objects of value accommodate more than just a hard set of diverse biological traits, as illustrated in this exchange:

“But what I expect from the goats is that everyone is happy – myself and the goats – and that we all get a decent living because, well, because they give good milk. Because I try to make sure that they get the best life possible, and give us milk, and then we sell the cheese and we are happy with that.”

Both the aesthetics factor and the considerations around overall satisfaction, as expressed in the interviews, carry an emotional dimension, and this emotional dimension will translate into how an animal population is managed. It is worth noting that the emotions expressed formed a subtheme of the ‘human-animal relationship’ theme. Although this is not the focus of this paper, it highlights how emotions are connected to attachment to animals. In an illustrative example, one farmer said:

“It’s the city; I don’t like it there and I miss my goats, so I don’t like being away from them for too long.”

And one added:

“In time, you start to love these animals. There’s really something special about goat farming.”

Farmer narratives on balance and trade-offs

Finally, listening to the farmer's accounts of the broad diversity of features they value, a challenge emerged: how to integrate these diverse features, or in other words, how to find balance or manage trade-offs. The farmers’ narratives are effectively punctuated with stories that talk about balance and trade-offs. We identified several ways in which this is expressed that employ a number of terms, such as “package”, “rounded”, or “balance”:

“You ask what I’m looking for in particular? It’s a combination, a package”

Or

“When I bought her, she was an instant favourite. She was a goat that had an angular, bone-led frame with a big head, which matched exactly what I was looking for in the Pyrenean. Very very long hair. She only had one udder, but she had been bucks dam for several years in a row. She had so much, she gave so much, gave a lot of milk too. So for me, she counted among the goats that I’d call ‘rounded’. She was a real favourite. Gentle, easy temperament – and she even lived to 16 years old.”

“You learn pretty quick that a goat that’s giving 3–4L of milk puts everything into milk and forgets to invest in immunity. So you have to find the right balance.”

How efforts to find balance and manage trade-offs manifest into practice

This effort to find balance is explained through farmers’ statements on their selection decisions within the Pyrenean goat breed population, or for renewal of their own herd.

Note that any trade-offs made will primarily depend on the perception of the focal traits and on whether selection can serve as a lever to achieving satisfactory goals. For example, one interviewee said they lend more importance to certain selection criteria on the grounds that other criteria, although important, are considered innate (i.e. inherently part of the breed’s make-up, and therefore not requiring active selection):

“Quite honestly, me, personally, I put type first: good legs, a big muzzle, good ears, hair. For me, type comes first. I know, it doesn’t sound logical, but... it’s because I think any Pyrenean goat has good yields already, it’s innate”.

In terms of ways to construct a compromise between traits to select for, the process can translate, for example, as (1) expressing a set of several traits to be co-selected together as a set, or (2) prioritizing criteria by first selecting for one and then selecting for others. The following farmer’s narrative illustrates, for instance, approach (1):

“Always looking for ways to continue selecting for both type and milk, without putting one ahead of the other. I really think you can manage to get both. You have to work on it, but you can get both.”

This other farmer’s narrative is more illustrative of approach (2):

“I’m in a performance recording programme, so obviously I look at growth. Growth in my herd first. Then I’ll adjust depending on maternal prolificacy, maternal hardiness.”

Discussion

A diversity of farmers’ objects of value in animals

The variety of farmers’ objects of value lead to a reconsideration of how animal diversity is characterized. Multiple objects of value were often observed grouped together, which means that farmers’ concerns revolve around accommodating balances and trade-offs. This diversity also shows that while typical zootechnical categories, such as performances and abilities, may work for a number of elements that farmers wish to see, these categories fail to encompass the full range of elements valued. This insight prompted us to further explore the notion of ‘breed attribute’, as proposed in our previous research, to account for zootechnical characteristics of local-breed animals alongside characteristics connected to other dimensions, such as their importance for sustaining local cultures and communities (Nozières-Petit & Lauvie, 2018; Lauvie et al, 2023). Although these attributes effectively connect to diverse functionalities provisioned by local-breed animals, here we found that this purely functionality-driven vision is too narrow, as our results showed that experiential or emotional dimensions may also come into play. The objects of value expressed by farmers are more than just ‘zootechnical’, reflecting a diverse set of potential reasons for choosing one animal or breed over another. Farming livestock as a livelihood is also associated with other dimensions that carry meaning to farmers. From this perspective, the features of discourse that translate the relational dimension and the emotions involved warrant attentive investigation. There is a compelling rationale for developing research at the intersection of zootechnics and sociology or zootechnics and philosophy that looks at relational bonds between humans and farm animals (see Porcher, 2001; Despret and Meuret, 2016). In a report on the results of her thesis research, Porcher (2001) argues that affectivity is an integral part of working with livestock and that this affectivity component has been underconsidered in research on animal welfare (which was her original starting point). The object of related research has thus shifted towards the study of work, i.e. the study of how animals and humans work together. To refocus research on the management of farm-animal populations, a promising approach is to better account for human–animal relationships in the analysis of livestock farming practices, starting by looking at how breeders talk about and describe these relationships and the way these relationships interact with specific practices and contribute to the satisfaction breeders get out of their work.

It is worth noting the example of a farmer who considered the occasional stubbornness of animals in his herd – when they refused to obey his command – as a positive trait. Although this only emerged from one interview, it offers an insightful starting point for defining the perimeters (in terms of objects addressed), strategies and paradigms engaged by disciplines dealing with the management of genetic resources. This is because this kind of discourse challenges the traditional strategy. Rather than projecting methodical control, it embraces the idea of ‘working with’ (composer avec in French, borrowing from the title of Despret and Meuret (2016) cited above), of ‘following/guiding nature’ rather than trying to control it (Morin, 1980). More broadly, attending to what it means for humans to work with living beings would help address a question that is pivotal to the principles of agroecology (Hubert, 2020).

From a methodological perspective, one way to further pursue this research would be to produce the most accurate description possible of farmers’ practices, particularly in terms of decisions around which animals to retain in the herd, but also, more broadly, the relationships that form between farmers and animals at key points in livestock management. This methodological approach could usefully combine interviews tailored to capture these points with direct observation of practices. Equally important would be a diachronic approach enabling specific attention to the way farmers effectuate changes in their practices (integrating their own analysis of the outcomes of their practices), in order to introduce a dynamic perspective where values are not seen as immutable. It is at this juncture that we address the formation of values as theorized by John Dewey, and as stated by Bidet et al (2011), who conceptualize valuations purely as behaviours that are situationally observable; consequently, a valuation cannot be reduced to a representation.

Pulling together everything that farmers value: selection as a lever in multidimensional and relational approaches

As stated in the introduction, one of the key motivations for focusing on what farmers value in their herds was to inform fresh thought on managing genetic resources in farm-animal populations. However, our findings resonate strongly with the questions being raised in selection programmes for farm animals. One challenge identified for genetics is diversifying the objectives of selection programmes. This involves defining breeding objectives that balance production traits with functional abilities. Such diversification is crucial for advancing the agroecological transition (Phocas et al, 2016). This trend finds confirmation in the diversity of traits that the farmers surveyed considered important. At the same time, they emphasize the effort to find balance and trade-offs, which aligns with models that consider herd management and genetic selection together while examining trade-offs among multiple performances and abilities within a herd (see Douhart, 2013). To complement these modelling approaches, characterizing how farmers translate this effort to find the right balance and trade-offs into practice could provide insight into the different ways these choices come together. Furthermore, the strong links between animal traits and flock management, and between animal traits and flock environments, that emerged here in the farmers’ narratives are also in line with recent work by geneticists to better characterize livestock breeding environments and account for genotype–environment interactions (Phocas et al, 2016; Hazard et al, 2017). This observation argues for bridging disciplines to bring scientific communities together – the genetics community and the livestock farming system community, and even reaching out to ecologists and social scientists. Mobilizing farmers’ field knowledge of their animals and their local farm habitats – and possibly even the ways they describe how these two factors, i.e. animals and habitats, intersect and interplay – also appears to be a promising direction for developing this research front.

Finally, diversity has also been identified as a pivotal issue and a key resource for making genetic selection better adapted to addressing agroecology challenges (Phocas et al, 2016). However, the local-breed farmers studied here considered and valued such a diversity of dimensions that they cannot viably be reduced simply to a gene pool; therefore, it is important to consider the genetic dimension in conjunction with other dimensions of value embodied by local-breed animals. Ducos et al (2021) stress that a contribution of animal genetics to the diversity principle of agroecology requires going beyond approaches based on the search for an optimal animal with calibrated performances for standardized and controlled breeding environments, and adopting a more systemic view.

The convergence and complementarity between our findings and some of the central challenges for animal genetics highlight that the plurality of dimensions and relationships emerging from this work demonstrate how overly reductionist approaches fail to capture the full complexity of questions concerning the suitability of livestock animals to farming practices, environments and systems. We arrived at the idea that progress could be made by developing a relational approach that repositions genetics as one of several levers intersecting with livestock animals, farming practices and environments in the broadest sense, i.e. in their ecological dimensions, technical dimensions, social dimensions, and beyond. This would require even greater interdisciplinarity and transdisciplinarity, so that we move beyond simply devising selection programmes toward producing knowledge about a nexus of suitability between animals, habitats/environments, and the objectives breeders attach to their livestock practice. In this new approach, the lever of genetic selection would be reframed to articulate with other actionable levers by crossing boundaries to mobilize disciplines that develop systemic approaches, but also social sciences and the field knowledge of farmers and the wider stakeholder community involved in managing farm-animal populations. The type of approach envisioned here would aim to produce knowledge that is both more global (i.e. holistically including a diversity of knowledge sets and dimensions), situated (to address agroecology challenges) and operable (i.e. borrowing from practices that operate at animal, herd, and breed population scales).

A further avenue for extending this work would be to attach greater importance to the observable valuation processes at work at the breed-society scale. Indeed, the methodology developed in this article rests upon interviews and mainly focuses on individual values and valuation processes. The composition of our work team, built through a transdisciplinary process, included the facilitator of the association, who had good knowledge of the collective dynamics and discussions. This allowed us to check a certain consistency of the analysis. However, to better tackle the collective dimension of valuation, complementary methodologies could be used, such as focus groups, to investigate how farmers talk about what they value in their animals when they discuss this theme together. Participant observation of moments when collective decisions are made at the scale of the breed association could also be a relevant methodology. It would allow a better understanding of how those values are discussed (through which objects and themes, which kind of actions), and help identify around which values consensus is built (which play a role in holding the collective together). We take the stance that closer attention to situations involving collective management of animal populations that have been sidelined from major selection programmes is a potentially fertile approach to help identify configurations, relationships, questions and practices already at work, which could usefully inform processes of rethinking better ways to mobilize genetic resources – a challenge that is now high on the agenda in the field of genetic selection for both animal and plant species.

Conclusion

This study aimed to describe the full diversity of what farmers value in their local-breed animals. This entry point enabled us to characterize a wide-ranging diversity of their objects of value spanning zootechnical performances, adaptive capacities, behavioural factors, self-sufficiency (requiring little human intervention), appearance and aesthetics, genetic diversity, and more. We also demonstrated the overarching importance of trade-offs and efforts to find balance among different traits. Managing genetics to meet these expectations involves more dimensions than simply focusing on improving individual traits; it requires an integrated approach to livestock farming. This approach is situated, or, in other words, it takes into account the specificities of each situation, and it connects people with tools, practices and animals.

Supplemental Material 1. Verbatim accounts from the interviews in French, and their translation into English, as reported in the article.

Author contributions

Conceptualization/design of the research questions: AL, NC, MONP, FT; Conceptualization/theoretical framework: NC, AL; Methodology: AL, NC, MONP, FT; Formal analysis: AL, NC, MONP, FT; Supervision of the investigation (interviews conducted by a student): AL, MONP, FT, NC; Writing – first version of the original draft: AL; Writing – Completed original draft: AL, NC, MONP, FT; Writing – review and editing: AL, NC, MONP, FT.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank senior-year intern Blaise Dupuis for conducting the interviews that provided the material for this research. We also thank all the farmers who graciously set aside their time for these interviews. Metaform Langues translated the French draft of this paper into English. We thank the reviewers for their useful comments. This work was supported by the joint technology unit ‘UMT PASTO’ [‘Resources and transformations for pastoral livestock farming in Mediterranean regions’].

Conflict of interest statement

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Ethics statement

Farmers gave permission to conduct the interviews for the purposes of this research, and were fully informed about its purposes.

References

Bidet, A., Quéré, L., Truc, G. (2011). Ce à quoi nous tenons. Dewey et la formation des valeurs, In Dewey, J. La formation des Valeurs, traduit de l'anglais et présenté par Alexandra Bidet, Louis Quéré, Gérôme Truc. (Les empêcheurs de penser en rond/ La découverte) Paris, 5-64.

Boichard, D., Ducrocq, V., Fritz, S. (2015). Sustainable dairy cattle selection in the genomic era. J. of Animal Breeding and Genetics 132 (2),135-143. doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/jbg.12150

Couix, N., Lauvie, A., Verrier, E. (2023). Biodiversité domestique animale : à quoi tenons-nous ? In Lauvie, A., Audiot, A., Verrier, E. (eds) La biodiversité domestique. Vers de nouveaux liens entre élevage, territoires et société. (QUAE), 111-127.

Despret, V., Meuret, M. (2016). Composer avec les moutons, lorsque des brebis apprennent à leurs bergers à leur apprendre. (Cardère, hors les drailles) 154p.

Dewey, J. (1939). Theory of Valuation. Chicago University Press (French translation in Bidet et al, 2011)

Douhard, F. (2013). Towards resilient livestock systems : a resource allocation approach to combine selection and management within the herd environment. PhD Thesis AgroParisTech.

Ducos, A., Douhard, F., Savietto, D., Sautier, M., Fillon, V., Gunia, M., Rupp, R., Moreno, C., Mignon-Grasteau, S., Gilbert, H., Fortun-Lamothe, L., Lamothe, L. (2021). Contributions de la génétique animale à la transition agroécologique des systèmes d’élevage. INRAE Prod. Anim. 34(2), 79–96 doi: https://doi.org/10.20870/productions-animales.2021.34.2.4773

Dumont, B., Fortun-Lamothe, L., Jouven, M., Thomas, M., Tichit, M. (2013). Prospects from agroecology and industrial ecology for animal production in the 21st century. Animal 7 (6), 1028-1043.

Hazard, D., Larroque, H., González García, E., Francois, D., Hassoun, P., Bouvier, F., Parisot, S., Clement, V., Piacère, A., Masselin-Silvin, S., Buisson, D., Loywick, V., Palhiere, I., Tortereau, F., Lagriffoul, G. (2017). Caractérisation des environnements de production et de nouveaux phénotypes pour améliorer la sélection et l’adaptation des ovins et caprins dans des environnements variés. In FAO/CIHEAM Network for Research and Development in Sheep and Goats. Joint Seminar of the Subnetworks (Nutrition and Production systems) and Innovation for Sustainability in Sheep and Goats (iSAGE), Vitoria-Gasteiz, Spain, 2017-10-03 2017.

Hubert, B. (2020). Agriculture et alimentation. Les modèles de production questionnés : l’impératif du changement agroécologique. Raison présente 213 (1), 85-96. doi: https://doi.org/10.3917/rpre.213.0085

Lauvie, A., Thuault, F., Nozieres-Petit, M.O., Dupuis, B., Couix, N. (2022). Valuation of local breeds: methodological questions following interviews with Pyrenees goat farmers, In 73rd Annual Meeting of the European Federation of Animal Science, EAAP, Sep 2022, Porto, Portugal.

Lauvie, A., Alexandre, G., Angeon, V., Couix, N., Fontaine, O., Gaillard, C., Meuret, M., Mougenot, C., Moulin, C.-H., Naves, M., Nozières-Petit, M.-O., Paoli, J.C., Perucho, L., Sorba, J.-M., Tillard, E., Verrier, E. (2023). Is the ecosystem services concept relevant to capture the multiple benefits from farming systems using livestock biodiversity? A framework proposal. Genet. Res. 4 (8), 15-28. doi: https://doi.org/10.46265/genresj.MRBT4299

Macé, M. (2021). Parole et pollution. AOC Media Analyse Opinion Critique (29.01.21). url: https://aoc.media/opinion/2021/01/28/parole-et-pollution/

Morin, E. (1980). L’écologie généralisé Oikos. In La méthode 2. La vie de la vie (Ed. du Seuil), 15-97.

Moulin, C.H., Perucho, L. (2023). Biodiversité domestique et résilience des systèmes d’élevage. In Lauvie A., Audiot A., Verrier E. (eds) La biodiversité domestique. Vers de nouveaux liens entre élevage, territoires et société. (QUAE), 131-145

Nozières-Petit, M.-O., Lauvie, A. (2018). Diversité des contributions des systèmes d’élevage de races locales. Les points de vue des éleveurs de trois races ovines méditerranéennes. Cah. Agric. 27 (6), 65003

Phocas, F., Belloc, C., Bidanel, J., Delaby, L., Dourmad, J.Y., Dumont, B., Ezanno, P., Fortun-Lamothe, L., Foucras, G., Frappat, B., González-García, E., Hazard, D., Larzul, C., Lubac, S., Mignon-Grasteau, S., Moreno, C.R., Tixier-Boichard, M., Brochard, M. (2016). Review: Towards the agroecological management of ruminants, pigs and poultry through the development of sustainable breeding programmes: I-selection goals and criteria. Animal 10 (11), 1749-1759. doi: https://doi.org/10.1017/S1751731116000926

Porcher, J. (2001). L'élevage, un partage de sens entre hommes et animaux : intersubjectivité des relations entre éleveurs et animaux dans le travail. Ruralia ([En ligne], 09, 2001 accessed 15 February 2024. URL: https://journals.openedition.org/ruralia/278

Pyrenean goat breed association (2024a). Craba e caulet, la chèvre et le chou, bulletin de liaison de l’Association la Chèvre de race pyrénéenne, 41, 5 p.

Pyrenean goat breed association (2024b). Website of the Pyrenean goat breed association, l’association La chèvre de race pyrénéenne. https://www.chevredespyrenees.org/ (accessed 13 February 2024).

Vissac, B. (2002). Les vaches de la République: saisons et raisons d'un chercheur citoyen, INRA Editions.

1 Group of farmers within the breed conservation association that sets and selects breeding bucks