A small-scale assessment of the availability of EURISCO accessions

Erik Wijnker*, Theo van Hintum

Centre for Genetic Resources, The Netherlands, Wageningen University and Research, P.O. Box 16, 6700AA Wageningen, The Netherlands

* Corresponding author: Erik Wijnker (erik.wijnker@wur.nl)

Abstract: A critical assessment of plant genetic resource (PGR) availability in Europe reveals a significant gap between documented accessions and those that are practically obtainable for researchers and breeders. While the EURISCO database lists over two million accessions, a study of 100 random accessions found nearly 60% to be unavailable, challenging the assumption that a large number of documented accessions equals usability. Material from 52% of the approached genebanks could not be obtained within five months. The primary barrier was the inability to contact genebank staff, which points to a systemic issue in which PGR access is not always prioritized. Insufficient material for distribution and geopolitical issues were further causes of low availability. This indicates a threat to the effective utilization of European PGR and highlights an urgent need for genebanks to improve communication and operational capacity to ensure these vital resources become accessible for crop development and food security.

Keywords: Availability, EURISCO, PGR, plant genetic resources, SMTA

Introduction

The International Treaty on Plant Genetic Resources for Food and Agriculture (ITPGRFA) (FAO, 2009) defines plant genetic resources (PGR) for food and agriculture as: “any genetic material of plant origin of actual or potential value for food and agriculture.” PGR underpin global food security by enabling crop improvement to face the challenges of future food production.

In Europe alone, hundreds of genebanks have been established to conserve PGR ex situ. Their holdings are listed in aggregated databases such as Genesys PGR (Genesys, 2025) and FAO’s World Information and Early Warning System on Plant Genetic Resources for Food and Agriculture (WIEWS) (FAO, 2025a). According to policy documents addressing the ex situ conservation of plant genetic resources (PGR), such as the influential Third Report on the State of the World's Plant Genetic Resources for Food and Agriculture, over four million accessions are documented in Genesys with over two million accessions conserved in Europe (FAO, 2025b). Global Crop Conservation Strategies also use the aggregated databases as a source of information to determine the conservation status of crops and set priorities for future activities (Dulloo and Khoury, 2023). At first glance, such numbers suggest that a wealth of PGR is available and conserved. However, this assumption may be misleading as conserved material is not always accessible for use.

Because PGR are tangible assets, it is of crucial importance that stakeholders can access and use them. The availability of material in genebanks, however, is an issue. Personal communications with the user community, but also rare studies like Bjørnstad et al (2013), make it apparent that PGR access is limited. Bjørnstad et al (2013) requested PGR from genebanks globally that are contracting parties to the ITPGRFA and observed that ‘facilitated access’ is not that straightforward. They received material from only 44 countries out of the 121 approached. If PGR are to be of “value for food and agriculture” as noted in the definition of PGR by FAO, they must be available.

Defining PGR availability is not easy, as it has many dimensions. One prerequisite is that genebanks physically have material for distribution. Ex situ collections require a targeted infrastructure to ensure long-term safekeeping of material, which depends on stable genebank funding. Accessions are to be held under good conditions and be subjected to good genebank practice: proper documentation, regular viability monitoring, proper regeneration practices and the creation of safety backups. The FAO genebank standards (FAO, 2014; 2022) provide excellent guidance on such practices.

Equally important, however, is the ability of genebanks to deliver material to users. This requires efficient distribution systems, compliance with phytosanitary and legal requirements, and ensuring clear conditions of use. For example, material that is distributed for research purposes only – and therefore not eligible for commercialization – may be considered ’available’ but has little, if any, value to commercial breeding and food production. In practice, availability means that users have good access to accession information, are able to order and obtain accessions quickly (i.e. within weeks) under permissive and uniform conditions. The Standard Material Transfer Agreement (SMTA) is a well-established, standardized contract used for plant genetic resources shared under the provisions of the ITPGRFA.

The intention of this research was to provide an impression of current PGR availability in Europe for policymakers, researchers and the genebank community. To better understand the actual availability of PGR material in Europe, a small-scale study was conducted in which plant genetic resources were requested to assess their availability. PGR were selected from EURISCO, a large and complete European PGR database that is often used by stakeholders (Kotni et al, 2023).

This study was not designed to evaluate the functioning of individual genebanks. The names of individual genebanks and requested accessions have therefore purposely been omitted from this report. This study should also not be interpreted as a critique of EURISCO. EURISCO itself notes that the presence of data does not guarantee that the material will be supplied: “The presence of data listed in EURISCO does not provide any warranty that the respective collection holders will be able to provide any plant material to interested parties” (ECPGR, 2025).

Materials and methods

Selection of the material to be requested

The general approach involved directly requesting a random set of PGR accessions and systematically observing the requesting process, the receipt of material and the conditions governing its use. Material was selected from EURISCO, the European Search Catalogue for Plant Genetic Resources that is maintained by the European Cooperative Programme for Plant Genetic Resources (ECPGR) (Kotni et al, 2023), and serves as an important data source for both Genesys and WIEWS. Because of its completeness and frequent use by stakeholders, the EURISCO database provided a perfect starting point for this research. Availability was defined pragmatically as the ability to order material and receive it within five months. Material that was not obtainable within this timeframe was considered unavailable.

Given the high costs associated with maintaining and regenerating genebank materials, the number of requested accessions was deliberately kept low. A total of 100 accessions was randomly selected, representing 0.005% of records in EURISCO. Anticipating that no more than half of the requested accessions would be successfully obtained, the study was expected to use material from approximately 50 accessions or fewer. While the limited sample size constrains the statistical reliability of the availability estimate, it was deemed sufficient to provide a general impression of the availability of PGR accessions currently conserved by European genebanks.

On 14 January 2025, a complete EURISCO dataset in CSV format was downloaded from the EURISCO website (ECPGR, 2025), comprising 2,101,833 accession records. To refine the dataset and focus on plant genetic resources (PGR) that are conserved ex situ, two filtering steps were applied. First, the 682,541 records from the Nottingham Arabidopsis Stock Centre (EURISCO descriptor INSTCODE = “GBR140”) were excluded. Additionally, 5,697 records identified as in situ conserved material (EURISCO descriptor STORAGE = 60) were removed. Following these steps, 1,413,596 accessions remained.

To ensure proportional representation of genebanks while selecting 100 accessions at random, the 418 contributing institutes were sorted according to the number of accessions they recorded in EURISCO. One accession was randomly selected from the smallest institutes contributing to the cumulative first 1% of the total records, another from the next 1%, and so forth, up to the point where an individual institute contributed 1% or more of the total accessions. For those larger institutes, the number of selected accessions was determined proportionally to their contribution. For instance, the largest institute contributed 14.2% of the accessions in EURISCO; therefore, 14 accessions were randomly selected from its records. This selection methodology ultimately resulted in 100 accessions being drawn from 52 institutes (of which 38 contributed only one accession). With 52 institutes (spread over 23 countries), this selection includes 12.4% of all genebanks that contribute to EURISCO. It comprises 52 different species of plants, of which barley (12 accessions), bread wheat (7), common bean (6) and maize (6) were most prevalent.

Requesting the material

Guidelines for requesting seeds were established in advance, including the use of a standardized text for all requests through email. This standard text did not disclose the purpose of our requests, but when a statement of purpose was explicitly required (occasionally during online requests or later communication, the following text was provided: “In the framework of a methodological research project we are exploring the content of European genebanks in EURISCO and access to these valuable resources.” The depletion of valuable seed stocks was minimized by requesting small quantities (< 25 seeds) whenever the requesting process allowed specification of seed amounts. Requests for vegetatively propagated material were withdrawn once the holding genebank indicated that the requested accession could be provided. The requesting procedure consisted of two rounds of requests: an initial request in which all genebanks were approached, and a follow-up in which contact was sought with genebanks in which the initial request did not result in a response.

The initial request was made on 28 February 2025. An online search was conducted for the 52 selected genebanks to identify contact details or online ordering facilities. Material was preferentially requested via online ordering. When no clear online order form or selection system was available, requests were submitted via email or online contact/feedback forms using standardized texts. Requests were directed primarily to the email address indicated for ordering; if unavailable, contact was sought with the genebank manager, the genebank, or the associated institute, in that order. In the absence of a clear email address, the WIEWS listing corresponding to FAO of the institute (FAO, 2025a) was used. In five cases, emails were returned as “undeliverable,” prompting a search for alternative addresses. For one accession, a renewed search identified an online ordering facility, and in two cases, the initial email request led to referral to the online order site. The request cycle concluded once all institutions had been contacted via online order, email or online forms.

Approximately four weeks later (between 21 and 25 March 2025), follow-up emails were sent to the 23 genebanks that had not responded, or to inquire further about the status of our request. These reminders were directed to the previously used email addresses or submitted via online forms. Where possible, the institutes’ email addresses listed in the FAO WIEWS database were included in cc if no contact had been established during the initial request. When the initial request had been submitted through an online form, a separate email was sent to the WIEWS-listed address.

The received seed material was stored in the drying chamber of the Centre for Genetic Resources, the Netherlands (CGN), and seed amounts were determined. Two vegetatively propagated accessions were received, of which the number of viable cuttings was recorded.

Results

Requesting the material

For two institutions (with one selected accession each), online searches for the genebanks yielded no leads, and WIEWS contact details were incomplete (no website or email). In a third case (one accession), the genebank indicated on its website that it was unable to accommodate new requests due to resource constraints. Consequently, material could be requested from 49 genebanks, covering 97 accessions.

When possible, material was requested through online ordering. Of the 52 selected genebanks (conserving 100 selected accessions), 17 (maintaining 55 accessions) allowed online searches of their holdings, including 4 genebanks (conserving a total of 9 accessions) using the GRIN-Global interface. Not all institutes permitting online searches offered online ordering. Seven initial requests were placed online, with an additional 5 following further inquiries, resulting in 12 institutions (23%) providing 31 accessions via online ordering.

Online ordering was not always straightforward, often requiring prior registration, navigating counterintuitive interfaces, or addressing technical errors that necessitated email contact. Some failures to order had other causes: one accession could not be located via the online interface and was later confirmed as no longer held, while two accessions listed as ‘unavailable’ on a GRIN-Global interface were requested via a contact form but received no response. Overall, experiences with online ordering varied from straightforward to frustrating.

Of the 49 institutions (97 accessions) that could be approached, 7 (14%) were initially contacted through online ordering. The remaining 42 were contacted through email (39 genebanks) or online forms (3 genebanks), making email the principal mode of communication for requesting genebank material. Email communication presented its very specific challenges: replies to requests were often sent from alternative addresses, causing changes in subject lines that complicated tracking of individual requests. Telephone requests were not attempted.

The initial 42 messages resulted in a reply in 18 cases (43%) but were not answered in most cases (57%): either no response was received (19 cases; 45%) or emails were returned as ’undeliverable’ (5 cases; 12%). Repeated efforts, including renewed searches, alternative addresses and reminder emails, allowed us to establish contact with 33 institutions (including the one indicating unavailability of all material in the collection on its website), while 19 genebanks (37%) remained unreachable, representing 40 accessions.

Effectiveness of our requests highly depended on live and actively monitored addresses. During the request process, WIEWS-listed addresses associated with the FAO code for the genebank used in EURISCO were often necessary, as no other contacts were available online. Of the 52 selected institutions, 6 had no email addresses listed in WIEWS, 6 addresses resulted in undeliverable emails, and 9 did not respond. Thus, at least 21 of 52 institutes (40%, representing 29 accessions) could not be reached via WIEWS-listed addresses. Some were nevertheless contactable through other online addresses. No systematic assessment of WIEWS address functionality was conducted; therefore, it cannot be assumed that the remaining 60% are reliably reachable.

Four requests (four accessions) were withdrawn by requestors during the requesting process. In two cases, requests were terminated after verification that material was available. This concerned a vegetatively propagated Rhododendron accession and an accession for which the holding institute indicated that the requested seeds were in short supply, but that a small amount could nevertheless be distributed. Two other requests (two accessions) were terminated without clarity on the availability status. These both concerned accessions that required special permissions to be granted (either by government or by breeders) prior to distribution: one CITES-protected species and one commercial grape variety. Both these accessions would – if permission were sought – be subject to MTAs rather than standard SMTAs and be available for research only. These accessions were classified as ‘possibly available.’

Availability of accessions

On 31 July 2025, five months after the initial request, the request period for this research was stopped. Starting from an initial list of 52 genebanks (100 accessions), it was possible to assess the availability of selected accessions at 33 genebanks (63%; 60 accessions). Contact was made with 32 institutes, and for one genebank (one accession), information for availability was derived from the website that indicated distribution was not possible. The remainder of 19 genebanks (37%; 40 accessions) could not be contacted through the channels used.

Data on accession availability are presented in Table 1, in which material is listed as ‘available’ if it could be obtained within a 5-month period, given the used communication/order methods. Of the 100 selected accessions, 38 were classified as ‘available’. Of these, 33 accessions were physically received from 19 genebanks (37%). Five accessions were not physically received, but availability was inferred from communication with genebanks: two accession requests were withdrawn (because of low stocks or vegetative material) and three accessions were lost in transit (sent but not received). A further three accessions were considered ‘possibly available’: one delivered as the wrong accession and two requiring additional, special permissions. The remaining 59 accessions were considered ‘unavailable’: 1 accession still in process, 18 accessions explicitly unavailable according to genebank feedback, and 40 accessions held by institutes that could not be contacted (Table 1).

Table 1. Availability status of requested material. Accessions have been grouped according to availability status, in which availability was defined as the ability to receive material within a 5-month period. *, Four genebanks could not provide all accessions requested and appear in both cells marked with an asterisk; **, The genebank total indicates the number of genebanks included in this study.

|

Availability |

Subgroup |

No. of genebanks |

No. of accessions |

Notes |

|

Available |

|

18 + 4* |

38 |

Material was either received (33 accessions), the request was withdrawn by requestors to save seed stock of prevent vegetative propagation (2 accessions) or material was lost in the mail (3 accessions) |

|

Possibly available |

Request withdrawn |

2 |

2 |

Material may be obtainable if special permission is requested and granted (availability for research only; MTA) |

|

|

Wrong accession was received |

1 |

1 |

|

|

Not available |

Genebank confirmed non-availability |

7 + 4* |

18 |

Material not available at genebank |

|

|

Long delivery time |

1 |

1 |

Ordering time exceeds the research limit of 5 months |

|

|

Genebank did not respond |

19 |

40 |

Material could not be requested due to no response |

|

Total |

|

52** |

100 |

|

For 60 accessions (33 genebanks), we obtained information on their availability (other genebanks could not be contacted or did not respond). Of those, 18 accessions (30%) were unavailable. Reasons for their unavailability were provided for 14 accessions, with a ‘lack of material’ being the most prevalent reason (8 accessions, 3 genebanks). Legal requirements prevented the distribution of two accessions, international armed conflicts prevented distribution of two accessions (two genebanks), one genebank indicated the inability to distribute any material on their website, and one accession was no longer maintained in the collection (Table 2). Availability via online ordering did not appear to correlate with seed availability. Of 31 accessions requested online (12 genebanks), 8 accessions (26%) were unavailable, similar to the overall unavailability rate of 30% for genebanks that provided feedback on holdings.

Table 2. Reasons for non-availability of requested material as provided by genebanks.

|

Reason for not sending |

No. of genebanks |

No. of accessions |

|

Genebank cannot distribute |

1 |

1 |

|

International agreements prevent distribution |

1 |

1 |

|

Lack of material/too few seeds |

3 |

8 |

|

Material is not disease tested |

1 |

1 |

|

No longer in collection |

1 |

1 |

|

War prevents sending |

2 |

2 |

|

No reason provided |

2 |

4 |

|

Total |

11 |

18 |

.

Distribution details, payments and conditions for use

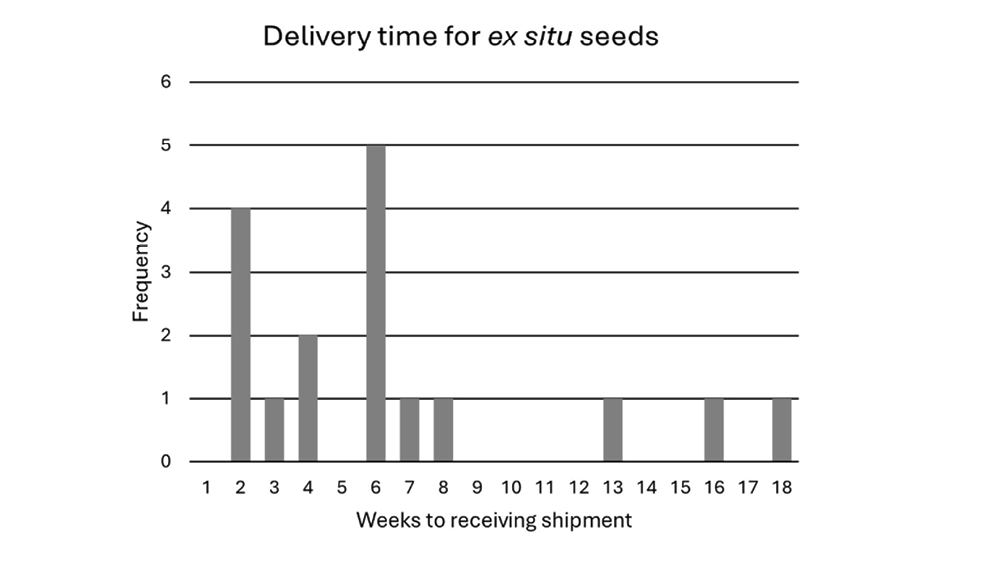

By recording the moment of parcel reception, the approximate delivery time for the requested PGR could be inferred (Figure 1). The majority of seed shipments (14 out of 17 packages) were received between two and eight weeks after initiating the request. The average time from first contact to accession receipt was six weeks. All received material arrived undamaged. Seed quantities per accession varied widely, ranging from 11 seeds (three accessions) to 381 seeds (one accession), with a median of 50 seeds. Clonal material (cuttings) was received from two institutes (two accessions) and was alive and viable upon arrival.

In three cases, payments were required as part of the request process. Two genebanks (two stations of the same institute) charged handling fees (€10 per request plus €2 per accession), and one genebank charged handling fees (€17) plus phytosanitary testing costs (€177) for two accessions.

The majority of received accessions (obtained from 19 genebanks) required a material transfer agreement (MTA). For 16 genebanks (84%; 30 accessions), a standard MTA (SMTA) was used, either signed manually with electronic exchange of documents (eight cases) or via click-wrap/easy-SMTA (eight cases). Two genebanks (providing one accession each) provided accessions without any user restrictions, and one genebank distributed under a different MTA. All 30 accessions received under SMTA were obtained from genebanks located in countries that ratified the ITPGRFA (FAO, 2009). The one accession obtained under a different MTA was received from a genebank located in a country that did not ratify the ITPGRFA.

Discussion

Access to PGR is a fundamental prerequisite for their effective utilization, and constitutes a central theme in international policy discourse, particularly in relation to access and benefit-sharing (ABS) mechanisms under the ITPGRFA. Despite the prominence of this issue, the practical conditions governing physical access to PGR remain insufficiently documented. Empirical investigations of this domain are scarce, with Bjørnstad et al (2013) being among the few to demonstrate that presumed availability of PGR is not always substantiated in practice. In light of this, a systematic assessment of PGR availability within Europe is both timely and imperative.

Although locating accessions via the EURISCO catalogue is relatively straightforward, the process of requesting material from the respective holding institutions proved considerably more challenging. For 22 genebanks (42%), we did not find a website dedicated to genebank activities (like describing collections and featuring genebank contact details). When websites did exist, the procedures for ordering material were frequently ambiguous. As a result, email emerged as the primary mode of communication. The request protocol was standardized and limited to two contact attempts per genebank, which was deemed a reasonable threshold for effort. While alternative strategies, such as translating emails into the local language, telephone outreach or leveraging personal networks, might have improved response rates, they were not employed in this study.

Of the 52 approached genebanks, 22 genebanks (42%) sent (at least part of) the requested material, which might have increased to 25 genebanks (48%) with additional effort (see Table 1). Likewise, it is estimated that the current availability of PGR accessions ranges between 38% and 41%, with the upper bound including accessions that may be obtainable through additional effort (see Table 1). Because of the small sample size, we suggest that this number be interpreted with caution. The average time required to receive seed material was approximately 6–7 weeks, a duration considered acceptable for most research and breeding purposes. Nevertheless, the study reveals that material from 27 genebanks (52%) could not be obtained, leaving 59% of accessions presently inaccessible. This highlights a significant and alarming proportion of inaccessible material in European genebanks.

The principal barrier to accessing PGR appears to be the difficulty in establishing communication with genebank personnel. The initial round of requests elicited responses from only half of the 52 genebanks contacted, which increased to two-thirds (33 genebanks) following a second round. Notably, one-third of the genebanks (19 out of 52; 37%) remained entirely unresponsive. The difficulty of contacting genebanks was also due to the unclarity and unreliability of contact information on websites or in databases, like WIEWS. While the reasons for non-responsiveness of genebanks are speculative, the data suggest that not all genebanks prioritize the facilitation of PGR access. These findings align with those of Bjørnstad et al (2013), who reported a similarly high rate of non-responsiveness among contracting parties in a global study on facilitated access.

Although EURISCO serves as a valuable repository for documenting PGR holdings, our findings indicate that actual access to these resources remains a significant challenge. Extrapolating the estimated availability rate of 38–41% to the broader EURISCO database (excluding Arabidopsis accessions) suggests that only approximately 481,000 to 594,000 accessions may be readily obtainable. This figure stands in stark contrast to the more than two million accessions currently documented, highlighting a substantial gap between nominal documentation and actual accessibility.

The sample size for our research was deliberately kept small: 0.005% of EURISCO accessions and 12.4% of contributing genebanks (including all those that contribute > 1% of all EURISCO accessions). Our estimate for availability is therefore to be interpreted with caution. Likewise, the small dataset limits the ability to statistically discern possible causes underlying seed availability. For example, requests to ten genebanks (19%) were directed to genebanks in four countries that did not ratify the ITPGRFA. Of the 25 requested accessions, 92% were classified as non-available. But assessing any effect of ratification of the ITPGRFA on availability would be confounded by the fact that nine of these requests were made to institutions in countries involved in armed conflicts during our research period (Israel, Russia and Ukraine). In this case, feedback provides more insight. Of the four genebanks from these countries that replied to our emails, ITPGRFA ratification was not mentioned as prohibiting seed distribution. Two of the genebanks did explicitly mention that the ongoing war prevented distribution (Table 2), indicating that PGR availability can be affected by geopolitical conflicts.

Europe hosts over 400 genebanks and collection holders in 43 countries that are listed in EURISCO, yet it remains unclear whether all institutions are actively conserving and distributing their holdings. This raises critical questions regarding institutional capacity and commitment to resource sharing. The observed challenges in distribution point to a disconnect between the documented inventory of accessions and their actual availability to users.

Many factors affect the availability of accessions from genebanks, ranging from expired email addresses to war. Even though this research could not address the underlying causes, elucidating these will be of the greatest interest to both genebanks and their stakeholders. For many genebanks, having material available for users touches directly on their raison d’être and may affect societal support for their work. For other stakeholders, a clear grasp of the underlying causes may help take measures to improve and promote PGR availability.

In conclusion, the findings of this study underscore the urgent need to address systemic barriers to PGR access in Europe. Failure to do so risks eroding valuable genetic resources, decreasing societal support for genebanks and impeding the capacity of researchers and breeders to develop resilient crop varieties essential for food security.

Author contributions

Both authors contributed equally to the manuscript

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the many enthusiastic genebank staff we interacted with during the course of our research. This work was carried out in the framework of the Programme Genetic Resources (WOT-03 and KB-34) funded by the Dutch Ministry of Agriculture, Fisheries, Food Security and Nature.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors have no relevant financial or non-financial interests to disclose.

Data availability

No data accompany this manuscript, but details on sampling procedures and collected data may be requested by contacting the authors.

Bjørnstad A., Tekle S., Goransson M. (2013). ‘‘Facilitated access’’ to plant genetic resources: does it work? Genet. Resour. and Crop Evol. 60, 1959-1965. doi: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10722-013-0029-6

Dulloo E., Khoury C. K. (2023). Towards mainstreaming global crop conservation strategies (Germany, Bonn: Global Crop Diversity Trust). doi: https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.7610356

ECPGR (2025). European search catalogue for plant genetic resources (EURISCO). http://eurisco.ecpgr.org

FAO (2009). International treaty on plant genetic resources for food and agriculture (ITPGRFA) (Italy, Rome; Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations). https://www.fao.org/plant-treaty/overview/text-treaty/en

FAO (2014). Genebank Standards for Plant Genetic Resources for Food and Agriculture. Rev. ed. (Italy, Rome: Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations). https://www.fao.org/3/i3704e/i3704e.pdf

FAO (2022). Practical guide for the application of the Genebank Standards for Plant Genetic Resources for Food and Agriculture: Conservation of orthodox seeds in seed genebanks (Italy, Rome: FAO Commission on Genetic Resources for Food and Agriculture). doi: https://doi.org/10.4060/cc0021en

FAO (2025a). World information and early warning system on plant genetic resources for food and agriculture (WIEWS). https://www.fao.org/wiews/data/ex-situ-sdg-251/search/en

FAO (2025b). The Third Report on the State of the World's Plant Genetic Resources for Food and Agriculture (Italy, Rome: FAO Commission on Genetic Resources for Food and Agriculture), 374 p. doi: https://doi.org/10.4060/cd4711en

Genesys (2025). Genesys plant genetic resources portal (Genesys PGR). https://www.genesys-pgr.org/

Kotni P., van Hintum T. J. L., Maggioni L., Oppermann M., Weise S. (2023). EURISCO update 2023: the European search catalogue for plant genetic resources, a pillar for documentation of genebank material. Nucleic Acid Res. gkac852. doi: https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkac852